Architects’ Furniture, 1960-2020

A cornucopia of furniture – designed by the world’s leading architects – reveals imagination rooted in practicality.

Cité de l’architecture et du patrimoine, Palais de Chaillot, Paris

29th May – 30th September, 2019

WHAT DISTINGUISHES ARCHITECTS’ furniture from that by designers? This is what the curators Lionel Blaisse and Claire Fayolle have addressed in this extensive exhibition, which assembles nearly 250 pieces by 120 architects, including Frank Gehry, Zaha Hadid, Lina Bo Bardi and Shigeru Ban. Dating from the 1960s, the works are dispersed over the venue’s five levels, intermingling with permanent pieces. The thematic scenography includes sections on: research-based projects; architects who have primarily dedicated themselves to designing furniture; those who have made it occasionally; and the role of manufacturers.

Installation view

COURTESY: © Cité de l’architecture & du patrimoine / PHOTOGRAPH: Denys Vinson

The start year of 1960 pinpoints how architects’ post-Second World War activities differed between countries. While French architects focused on reconstruction, the Scandinavians Arne Jacobsen and Alvar Aalto – whose countries had not been heavily bombed – continued to make furniture. The second curatorial concern is: “What is an architect?” Blaisse and Fayolle excluded practitioners who design buildings, but are not qualified architects – as well as qualified architects who have never designed a building. This second criterion ruled out the Italians Andrea Branzi and Enzo Mari, unlike their contemporaries Ettore Sottsass, Gaetano Pesce, Joe Colombo and Alessandro Mendini.

How architects approach furniture design, and how this relates to their architecture, is richly explored. “Just as architects know when they start designing a building whether it will be in a concrete or metallic structure, they ask themselves about the material, production method and maintenance when they design a piece of furniture,” Blaisse says. “Very often, they create specific pieces for precise purposes.”

Installation view

COURTESY: © Cité de l’architecture & du patrimoine / PHOTOGRAPH: Denys Vinson

The domain of furniture can serve as a laboratory to research ideas and interests. For instance, in 1939 Franco Albini designed the ‘Veliero’ (meaning sailing boat) – a transparent bookcase that would divide his large living room. The articulation of poles and elements recalling his passion for sailing, Albini would frequently adjust its cables. When his heirs invited Cassina to edit it in 2011, Renzo Piano – another sailing aficionado – was one of three people called upon to make it more stable.

Franco Albini, ‘Veliero’ bookcase, 1938, Cassina

COURTESY: © Cassina

Jean Nouvel has frequently created furniture and lighting for the museums that he has designed, just as Bo Bardi made the ‘Girafa’ (1987) chair for the restaurant in the Casa do Benin cultural institute she designed in Salvador da Bahia.

Lina Bo Bardi, Marcelo Ferraz and Marcelo Suzuki, ‘Giraffe’ chair, 1987, Marcenaria Baraúna

COURTESY: © Lina Bo Bardi, Marcelo Ferraz et Marcelo Suzuki © Baraúna

The signature qualities of an architect’s language is often immediately apparent in their pieces, from the wavy ribbons of maple in Gehry’s ‘Power Play’ armchair (1992-1993, Knoll) to the dynamic radicality of Hadid’s ‘VorteXX’ chandelier (2005, Sawaya & Moroni).

Frank Gehry, ‘Power Play’ chair, 1992, Knoll

COURTESY: © Knoll International © Frank O. Gehry-Cnap / PHOTOGRAPH: Bruno Scotti

Elsewhere we see what can be achieved by stretching the possibilities of digital technology or natural materials. Take Thomas Heatherwick’s undulating and dramatic ‘Billet 1 – Extrusion 1’ (2009). Culminating from 18 years of research and harnessing aerospace technology, it was produced by heating up a single ‘billet’ of aluminium and pushing it through the die of the largest extrusion machine at that time – before being mirror-polished for 300 hours.

Thomas Heatherwick, ‘Billet 1 – Extrusion 1’, 2009

COURTESY: © Peter Mallet Photography

By contrast, the ‘Ecoire Chair’ (2016/2017) by Daniel Widrig and Guan Lee at University College’s London Material Architecture Lab was made from coconut fibre and starch. Its twisting, symmetrical form gives the impression of coconuts being ensconced inside.

MAL – Daniel Widrig and Guan Lee, ‘Ecoire Chair’, 2017

COURTESY: © MAL-Daniel Widrig and Guan Lee

There are also spotlights on Brazilian and Japanese architects. As Blaisse says, “We wanted to show the exceptions to western design: how people in Japan live close to the ground and nature, and how the construction of Brazil’s new capital, Brasilia, heralded a new culture of furniture – thanks to Brasilia’s architect Oscar Niemeyer commissioning Sergio Rodrigues to design furniture [for the offices of public buildings].”

On display is Rodrigues’ ‘Mole’ brown leather armchair (1957), originally designed for the photographer Otto Stupakoff who wanted a sofa to sprawl out on for his studio. When it won first prize in a competition in Italy four years later, Jacobsen declared that it communicated the unique characteristics of Brazilian culture. Indeed, Rodrigues became known as the father of modern Brazilian design. Four decades later, Fernando and Humberto Campana’s ‘Vermelha’ armchair (1998, Edra), made by overlapping hundreds of twists of 500m of red rope, was inspired by the energy, chaos and beauty of São Paulo.

Humberto and Fernando Campana, ‘Vermelha’ armchair, 1993, Edra

COURTESY: © Fernando & Humberto Campana-photo Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, Dist RMN-GP

Works by the Japanese architects reflect their sensitivity to nature. Toyo Ito’s ‘Sendai – Horm’ (2004), open bookcase, with irregular, vertical pieces of wood, references the arborescent structure of the Sendai Mediatheque in Japan. Similarly, Ban’s ‘Carta’ chair (1998, Cappellini) made from paper tube structures (PTS) and plywood legs, recalls his use of PTS in emergency housing and humanitarian projects (such as the Cardboard Cathedral in Christchurch, New Zealand, following the 2011 earthquake).

Shigeru Ban, ‘Chair L-Unit System’, 2002, Cappellini

COURTESY: Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais-Georges Meguerditchian

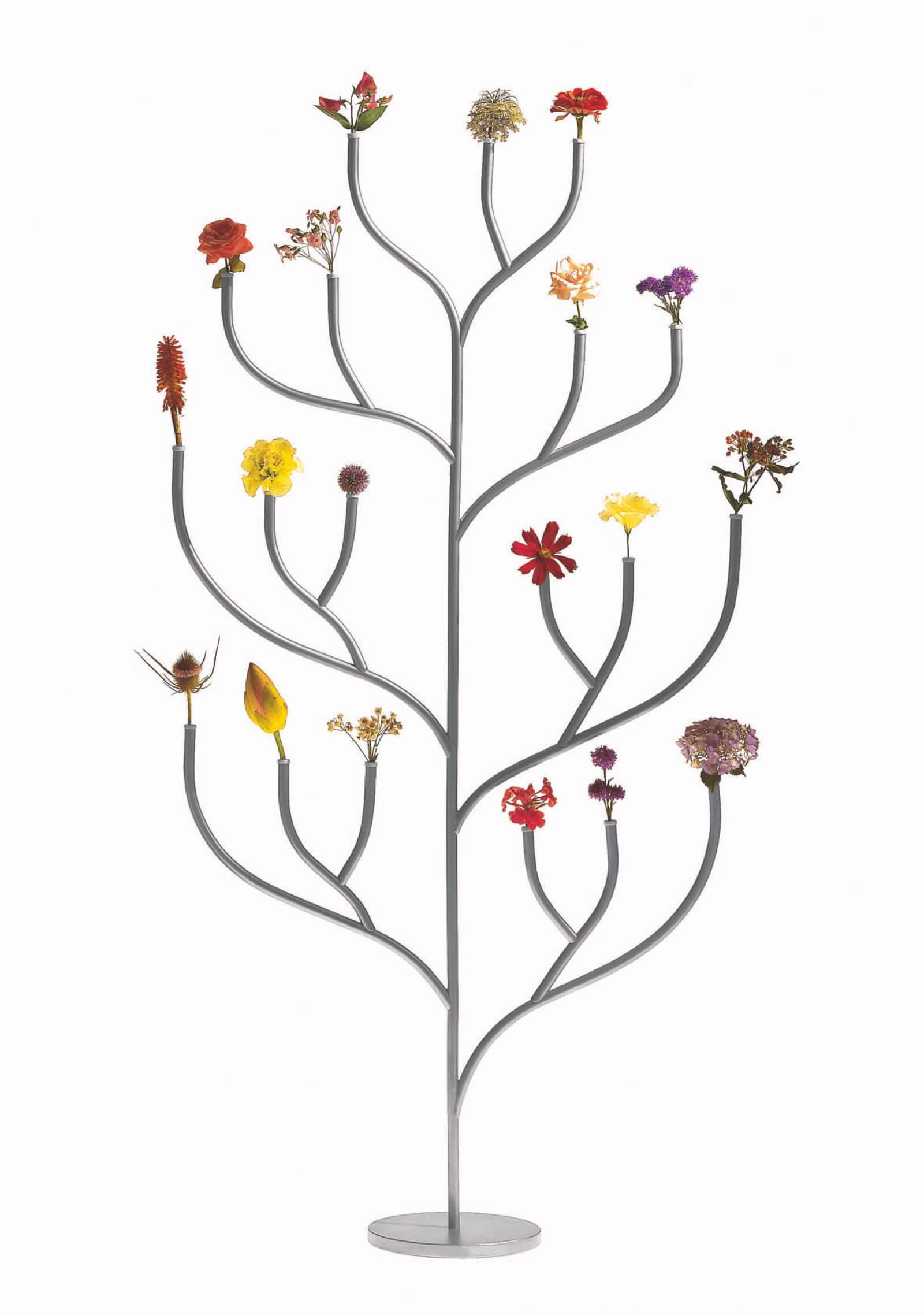

Junya Ishigami’s ‘Family Chair’ (2010, Living Divani) – a white, painted steel collection evoking variously shaped family members – captures the lightness and playfulness embodied in his architectural projects. And Sejima’s ‘Hanahana’ (1999, Driade), an elegant, stainless steel tree-vase whose branches have tips for inserting flowers, encapsulates the delicate poetry of SANAA’s buildings. As with many of these architects, these pieces underscore the interrelationship between life, objects and architecture.

Kazuyo Sejima, ‘Hanahana’, 1999, Driade © Driade

COURTESY: © Driade

Cité de l’architecture et du patrimoine – is a museum of architecture and monumental sculpture located in the Palais de Chaillot, in Paris, France.