Ai Weiwei / The Liberty of Doubt

“My work is focused on the meaning of making and the tradition of craftsmanship."

Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge

12th February – 19th June 2022

Ai Weiwei

COURTESY: Ai Weiwei & Kettle’s Yard / PHOTOGRAPH: Helen Dickman

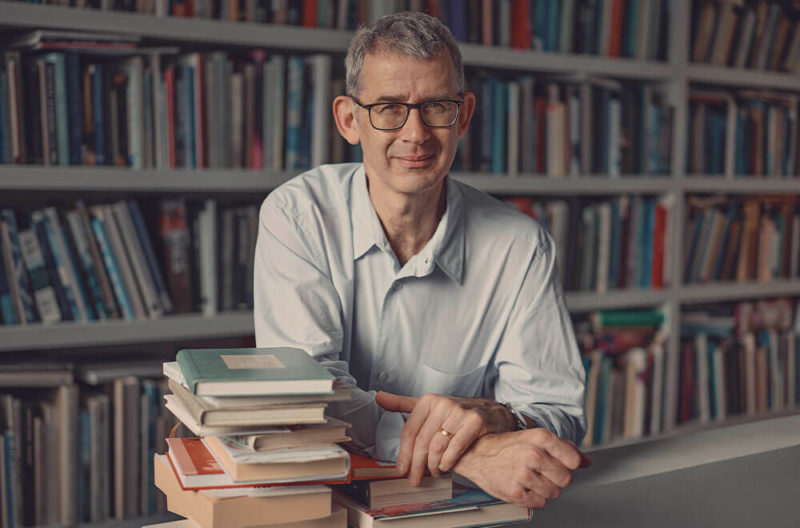

ON 12TH FEBRUARY, Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge opened a new solo show of work by the Chinese artist Ai Weiwei. The artist, in exile from China, a political dissident as much as an artist, says “I can now call Cambridge my home.” Of the beautiful house – once the home of Tate curator Jim Ede, whose substantial collection, of modern art and antique and modern furniture and objects, is displayed with sensitivity throughout the domestic space – Ai Weiwei says, “I like Kettle’s Yard because I think I belong to it.”

One reason may be that while Ai Weiwei’s work, across many media, is driven by his concern for contemporary issues of free speech, surveillance, migration, globalisation and value, much of it is rooted in made objects, of many eras. As he told the gallery’s director, Andrew Nairne, “My work is focused on the meaning of making and the tradition of craftsmanship. Take the tradition of jade – a stone, picked up from a river, and people give it such power!” In one room, a pair of jade handcuffs, modelled on those used when Ai was arrested by the Chinese authorities, and a jade mobile phone, meticulously created by Ai’s craftsmen collaborators, illustrate the jarring discordances of artistic tradition with contemporary experience.

The show’s inspiration is a collection of Chinese antiquities Ai bought from a Cambridge auction house in 2020. At the time he was unable to examine the pieces in person, making the winning bids on his phone. On his return he found a mixed bag: some of the pieces are thought to date from the Northern Wei (386 – 534 CE) and Tang (618 – 907 CE) dynasties, while others have been identified as counterfeits, later copies of original works. These carved Buddhist figures are displayed with equal prominence in elegant wood and glass display cases, commissioned by Ai, questioning our fixed Western notions of ascribing value by authenticity, and emphasising the way these migrant objects are isolated from their original cultural context, subject to the categorisations of Western scholars.

‘A Chinese white marble Buddhist deity’

COURTESY: Ai Weiwei Studio

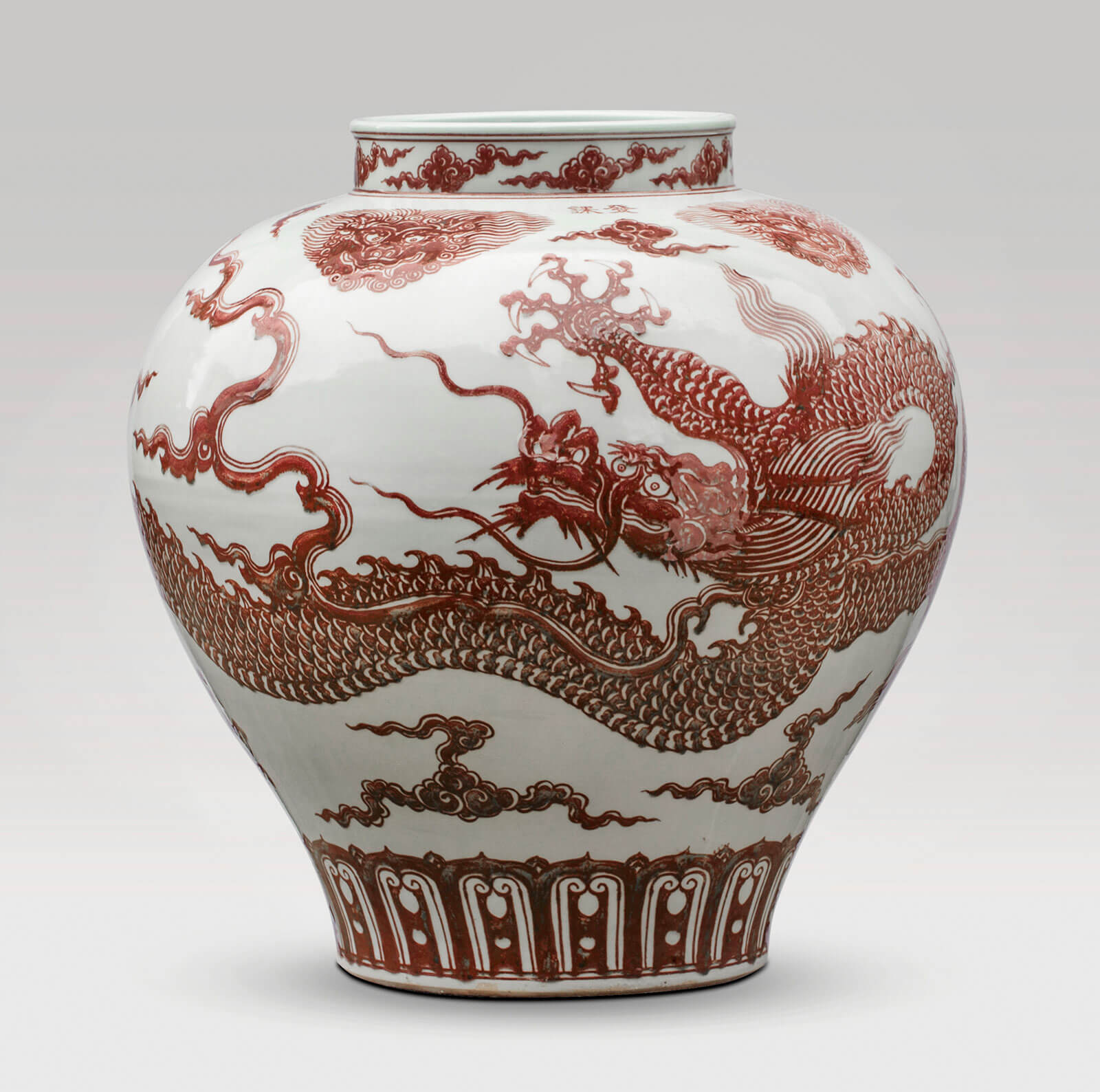

Alongside stands a ‘Dragon Vase’ designed by Ai, dating to 2017, a nearly exact replica of an auction record-breaking Ming vase, the dragon depicted in the red glaze prized by Chinese emperors. If Ai’s replica were a mere copy it would have little value for Western audiences. With subtle differences to the imagery, and in the context of an argument about authenticity, it becomes an original artwork by a world-renowned artist. The object’s sheer beauty is just one element in these swirling calculations.

Ai Weiwei, ‘Dragon Vase, 2017’

COURTESY: Ai Weiwei Studio

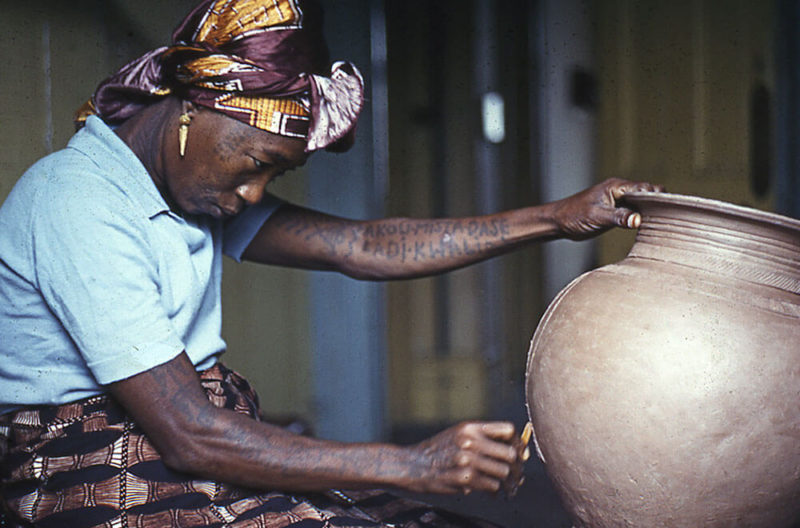

This is the first time that Ai has displayed authentic Chinese works alongside his own. A second room includes an authentic Han dynasty pottery ‘cocoon’ Funerary Jar – highly prized because it will be enjoyed by the deceased in the heavenly realm – alongside a Han Dynasty urn with a Coca-Cola logo, from 2014, with which Ai questions how we ascribe value today.

Ai Weiwei, ‘Han Dynasty Urn with Coca-Cola Logo’, 2014

COURTESY: Ai Weiwei Studio

There is also a series of six archetypal blue-and-white porcelain plates from 2017. Far from traditional patterns, the plates are covered with images, drawn equally from the internet, Ai’s own film-making and early Greek and Egyptian carvings – drawing links between the Greek story of The Odyssey and the ongoing global refugee crisis. Culture and human experience seem as fluid as the meanings of these objects: in a constant state of uncertainty, ambiguity, and renewal.

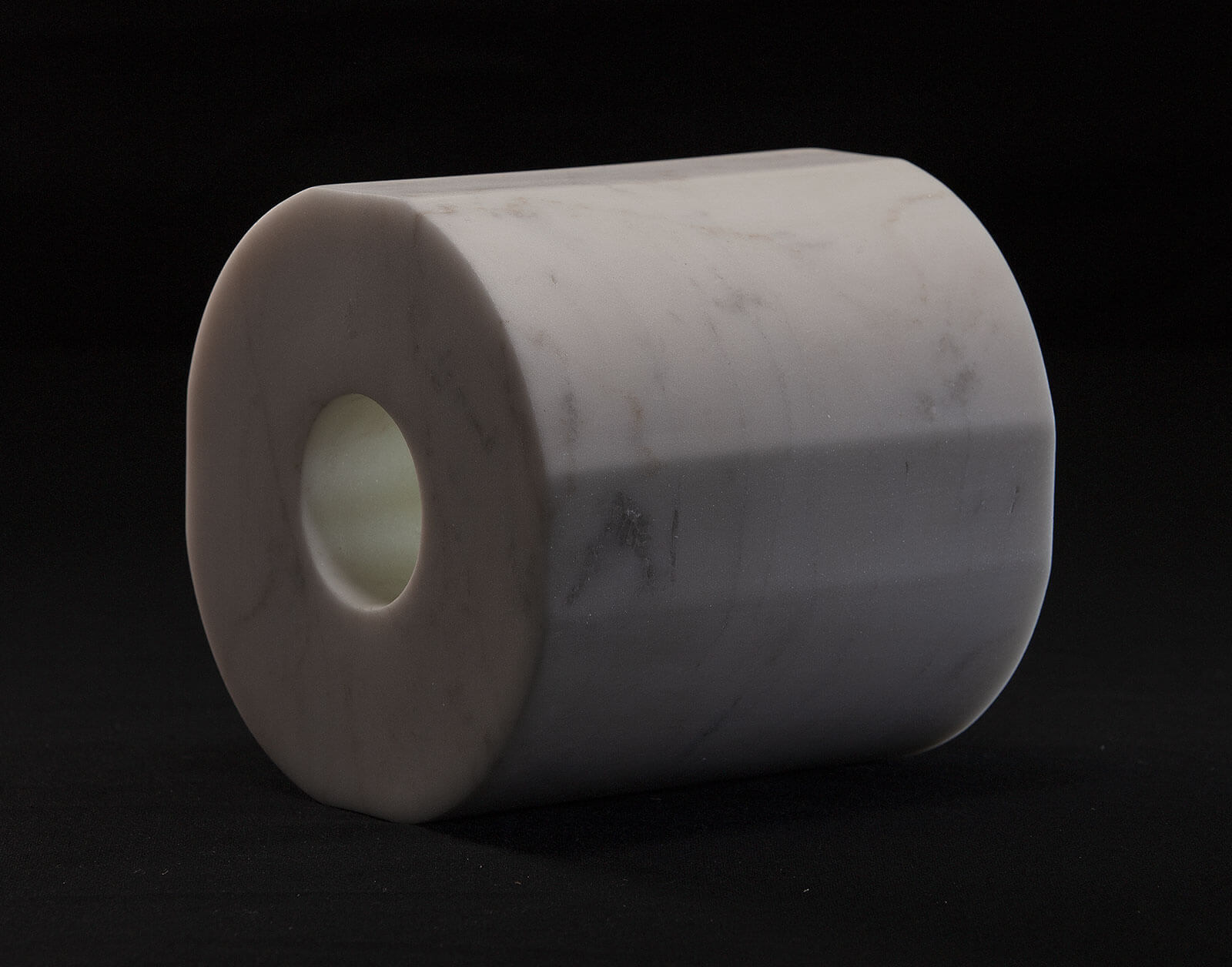

Ai Weiwei, ‘Marble Toilet Paper’, 2020

COURTESY: Ai Weiwei Studio

In an interview with The Design Edit, Ai suggests that while many in the West enjoy freedom of speech, we do not like to doubt – we like to pin things down. Ai says, by contrast, “In Chinese wisdom, humans are part of the environment, the environment is unpredictable, it is a situation of giving and taking, we are not dominant in the world.” He adds, “We do not have this religious belief in one God, and all the structure of guilt and punishment, we just don’t have it. People in the West may seem to be more liberal, in today’s sense of the word. But you can see in the West today that we are still trying to find a truth that can dominate, and there is no such thing.”

Instead what matters to Ai is imagination – to find, through making art, a way of expressing the fleeting truth of your own moment. He says, “What is imagination? It is like a kind of desire, it is always about something we don’t have.” Rather than art confirming what we already know and what we already possess, Ai says, “Art helps me to heal. What needs to be healed is the imperfection of a life if it is not conscious.”

Ai Weiwei: The Liberty of Doubt at Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge.