Daniella Ohad / The Female Voice

"I was only interested in pieces that were totally original, totally reflective of the zeitgeist: work that contributed to the story of modern design."

Carpenters Workshop Gallery, New York

20th April – 3rd July 2022

Design historian Daniella Ohad talks to writer and curator Natalie Kovacs about ‘The Female Voice in Modern Design: 1950-2000’, a show of landmark works by pioneering women designers.

Gabriella Crespi, ‘Cubo Magico’, 1970

COURTESY: Gabriella Crespi & Carpenters Workshop Gallery

Natalie Kovacs (NK): This exhibition seems to present both a historic survey of women’s unprecedented contributions to the evolution of design, and a cultural timeline for modernity. With a 50 year time frame, how did you select which works to include in the exhibition?

Daniella Ohad (DO): What I was looking for was these shining moments … because these women had very long careers. But in design there are usually these shining moments – not just for the designer, but also for design culture. So I was only interested in pieces that were totally original, totally reflective of the zeitgeist: work that contributed to the story of modern design.

Gabriella Crespi, ‘Cubo Magico’ (detail), 1970

COURTESY: Gabriella Crespi & Carpenters Workshop Gallery

Also, because I’m working for Carpenters Workshop Gallery, I wanted to fit this show into their DNA – meaning that the pieces had to be collectible. My definition of ‘collectible’ is not how it is often interpreted today, when everybody calls themselves collectible: collectible art fair, collectible this, collectible that. No, my definition of ‘collectible’ is very, very straightforward: ‘collectible’ is the best design of the period. I use ‘collectible’ in the quality and historical sense.

Line Vautrin, ‘Soleil à Pointes, Mod. 4’, 1955

COURTESY: Line Vautrin & Carpenters Workshop Gallery

NK: That makes perfect sense, history has always informed the gallery’s decisions about what to commission or exhibit. What was the genesis of this particular show? When did the idea emerge?

DO: Carpenters Workshop Gallery wanted to do something with me, so that’s how it started. We quickly arrived at the idea of doing something timely and meaningful and it was a natural evolution to explore vintage women designers.

Vera Szekely, Pierre Szekely, André Broderie, ‘Coupe Griffe’, 1955

COURTESY: Vera Szekely, Pierre Szekely, André Broderie & Carpenters Workshop Gallery

NK: What was your criteria for the selection? Composition, form, material utility?

DO: One of the very important criteria was that the work was available. Remember, it’s a gallery show and everything there is for sale. In addition, it was not about composition, or the other things you mention, it was really about what I said before – the shining moments.

Vera Szekely, Pierre Szekely, André Broderie, ‘Coupe Griffe’, 1955

COURTESY: Vera Szekely, Pierre Szekely, André Broderie & Carpenters Workshop Gallery

NK: What is so fascinating is the way in which we travel through time in this show to explore everything from hemlines, space travel to the fantasy of the perfect home – the political and social shifts and how they were expressed through design. Was it clear from the get-go that it had to be a by-the-decade show, or was there a certain moment in your research that informed this framework?

DO: The chronological evolution, by decade, is very important. For me it’s the only way to look at the story of modern design. Good design responds to the social, economic and political issues of the time. It is only when you examine design by time that you can really understand that aspect. The exhibition designers, AtelierTek Architects, wanted to communicate the decades to people, so decided to do it by colours. Each decade has a colour.

Ingrid Donat, ‘Petite Console aux Caryatides’, 1998

COURTESY: Ingrid Donat & Carpenters Workshop Gallery

Ingrid Donat, ‘Petite Console aux Caryatides’, 1998

COURTESY: Ingrid Donat & Carpenters Workshop Gallery

NK: One thing that came across my radar as I was reading was that a lot of design was local at the beginning. Then designers formed these groups and companies, and suddenly design became a more international movement. When did the market really pivot towards a global enterprise?

DO: The global aspect of the design market started in the 1950s, though it was still limited. Italian design, for instance, was promoted in America at that time through exhibitions – the Brooklyn Museum had a show in 1950, ‘Italy at Work: Her Renaissance in Design Today’, while, over twenty years later, in 1972, MoMa ran ‘Italy: The New Domestic Landscape’. There were also companies, such as Singer & Son, an American firm that had a contract with Gio Ponti and produced his furniture in America. And Gabriella Crespi had representation in New York in the 1970s.

Gabriella Crespi, ‘Folding Chairs, Set of 8’, circa 1973

COURTESY: Gabriella Crespi & Carpenters Workshop Gallery

NK: What role did women play in the globalisation of the design market through mass affordable production? Which pivotal or seminal works would you say informed the industry as it is today, or forever changed the game?

DO: Women were always at the margins. They were a tiny minority. In the eighteen months that I spent researching and doing acquisitions for this exhibition I was looking at all auction houses across the world. And in a season of say 3,000 lots of 20th century design, if there were 20 lots by women that would be a lot. So, when you talk about “changing the game”, whatever was done it was not women that were behind that change.

In addition, none of the pieces in the show is an example of true mass-production, they are instead extremely rare, as Carpenters Workshop Gallery is not about mass production.

Gabriella Crespi, ‘Folding Chairs, Set of 8′ (detail), circa 1973

COURTESY: Gabriella Crespi & Carpenters Workshop Gallery

NK: Which women designers, starting off in the shadows of their husband/partner, evolved to stand on their own?

DO: None actually. They always remained in the shadows of their partners. Let’s look at the women represented in this exhibition who worked with a man – Franca Helg for instance worked with Franco Albini. When do you see Franca Helg credited on Albini’s pieces? Only when it’s part of a very scholarly, or museum description.

Franca Stagi ‘Dondolo’ rocking chair, 1967

COURTESY: Franca Stagi & Carpenters Workshop Gallery

Take Luisa Parisi who worked with Ico Parisi. Up until about four years ago, when a monograph of Ico Parisi was published, nobody knew about Luisa. Let’s talk about Massimo and Lella Vignelli. Again, in their case they worked together so long and they were really active into the 1980s and 90s. I think it’s time that changed it, rather than a specific event.

Luisa Parisi (with Ico Parisi), ‘Pair of Lounge Chairs Model No. 865.’, 1955

1955

COURTESY: Luisa Parisi & Carpenters Workshop Gallery

NK: You’re right, I think it was linked to the women’s liberation movement and women’s voices becoming more accepted in general.

DO: Yes, and then there were the women who were always independent, like Maria Pergay and Gabriella Crespi, either from having money or getting really lucky with one commission that made their career. But it’s also interesting that in Finland there were a couple of strong female designers who were independent in the mid-century.

Maria Lindeman, ‘K10-2’ floor lamp, 1950

COURTESY: Maria Lindeman & Carpenters Workshop Gallery

NK: Are there any specific breakthrough moments exemplified by work in the show that you wish to highlight?

DO: As I said, in each case I was looking for the shining moment, the height of these women’s careers when they really contributed the best thing to design culture. For Gabriella Crespi, for example, what she did in the 1970s was the best. It was very zeitgeist. I think that her work in the 1980s wasn’t as powerful or strong. If you want to highlight another piece, it should be Gae Aulenti’s daybed, ‘Locus Solus’ from the 1960s. She had a very, very long career, but I felt that her work during the sixties is very much of the period. It looks like pop and it also shows her reinterpretation of early modernism. She looked backwards to the 1920s and created something that was completely innovative, completely 1960s, and completely bold in terms of the colours and form.

Gabriella Crespi, ‘Light Sculpture from Series Kaleidoscopes’, circa 1970

COURTESY: Gabriella Crespi & Carpenters Workshop Gallery

NK: Design is often born as a solution to a problem or difficulty, not simply an adaptation or ornament. Some of the earlier post-war designers of the 1950s certainly reflect that approach. Are there any works by these designers that you feel specifically addressed social change?

DO: The most famous example is to look at the difference between Charlotte Perriand’s 1950s pieces and the Jacqueline Lecoq pieces from the 1960s. This is the perfect narrative because Charlotte Perriand was very interested in formulating modernism for social change. She was interested in the 1950s. She understood that modern design could change the lives of millions. She knew that many people lived in such poverty that it prevented them participating in the evolution of the 20th century, so she worked with Le Corbusier to create furniture for housing projects.

When you look at Lecoq’s 1960s’ pieces you can see that they have a very different approach. In the early sixties, designers were no longer interested in this social look, industrial look, poor material look. They wanted something more chic. They wanted to relive something more elegant and sleek. That’s what you see in Lecoq’s pieces. They represent society’s shift in taste.

Charlotte Perriand, ‘Bahut Forme Libre’, 1939-1956

COURTESY: Charlotte Perriand & Carpenters Workshop Gallery

NK: Many of the women in the exhibition not only worked on creating designs and architecture but also on education – either teaching, writing about the history of design, or creating magazines to further design. Is there a link or common thread between these practices?

DO: You have to practise design and architecture in order to know how to teach design. If a teacher comes out of school and doesn’t practise, their teaching doesn’t have a quality to it. These women that worked in academia were practising designers. They needed income, so they found income through teaching. The combination of teaching design and practicing design is very natural. And so I believe from looking at all of this, that their motivation was really to remain in the working place in all of the streams of the working place: teaching, writing and practising.

Simone Prouvé, ‘Untitled 030695’, 1995

COURTESY: Simone Prouvé & Carpenters Workshop Gallery

NK: Geography plays a role in these designers’ expressions, to a degree, but in some cases their work travelled and impacted other cultures – such as Greta Magnusson-Grossman, who moved from Stockholm to Los Angeles. Was there any pivotal moment where a particular type of local design impacted a global language?

DO: I want to talk about the Finnish women who created lighting, but I’m not sure if that is going to answer your exact question. In Finland the days are very short, for a very long time. As a result, lighting is extremely important and there’s a lot of amazing lighting and expression in lighting in Finland – more than in many other countries in the world.

Lisa Johansson-Pape, ‘Hanging Wall Lights’, circa 1950s

COURTESY: Lisa Johansson-Pape & Carpenters Workshop Gallery

But I don’t know whether this impacted other cultures at the time. Perhaps it did more in the 21st century when the collectible design market started to emerge.

However Danish Modern was very strong in mid-century America. There were companies in America that imported Danish tableware and Danish furniture. Americans really loved it because it was cheap and it felt familiar as it was made in wood. It really had a strong impact on the design culture in mid-century America – in fact the Danish can really be credited for moving American taste away from antiques to Modern in the sixties and seventies.

But what Greta Magnusson-Grossman did was a little bit different. She came from Sweden and designed beautiful furniture in Los Angeles, but she wasn’t that influential. She wasn’t as prolific as the Eameses, or not enough to make everybody copy her.

Greta Magnusson Grossman, ‘Cobra and Cone’ shade table lamp, 1950

COURTESY: Greta Magnusson Grossman & Carpenters Workshop Gallery

NK: A lot of the female designers shifted materials and worked in different mediums from ceramics, to walls and jewellery. Is this something that is more innate for women designers than men do you think?

DO: No. I also want to mention that a lot of people talk about the design of these women as “feminine”. I don’t see that. I see these women participating in design culture as equals.

Zaha Hadid, ‘Moraine’, 2000

COURTESY: Zaha Hadid & Carpenters Workshop Gallery

NK: However, Eva Zeisel referred to her groupings and work as “family”. Would you say that this reflects the maternal instinct, at all, and its role in creating domesticity and warmth, and bringing organic forms and designs into our lives?

DO: Eva Zeisel created industrial design in ceramics. She was a wonderful designer and created mostly tableware. Yes, at one point she designed this ‘Town and Country’ dinnerware, and the pepper and salt look like they hug each other.

In the 1950s she decided to make furniture in ceramics. Think about it – free-standing furniture in ceramics! Then she created a series of room dividers. We have two of them, one in black, and one in black and white. It’s really one of the masterpieces of this show because it was made when the market was not really ready for it. It was very new. A ceramics room divider had never been seen in America and it never went into production as it didn’t have any commercial success. So what we have in this exhibition is totally one of a kind.

Eva Zeisel, ‘Room Divider Black’, 1958

COURTESY: Eva Zeisel & Carpenters Workshop Gallery

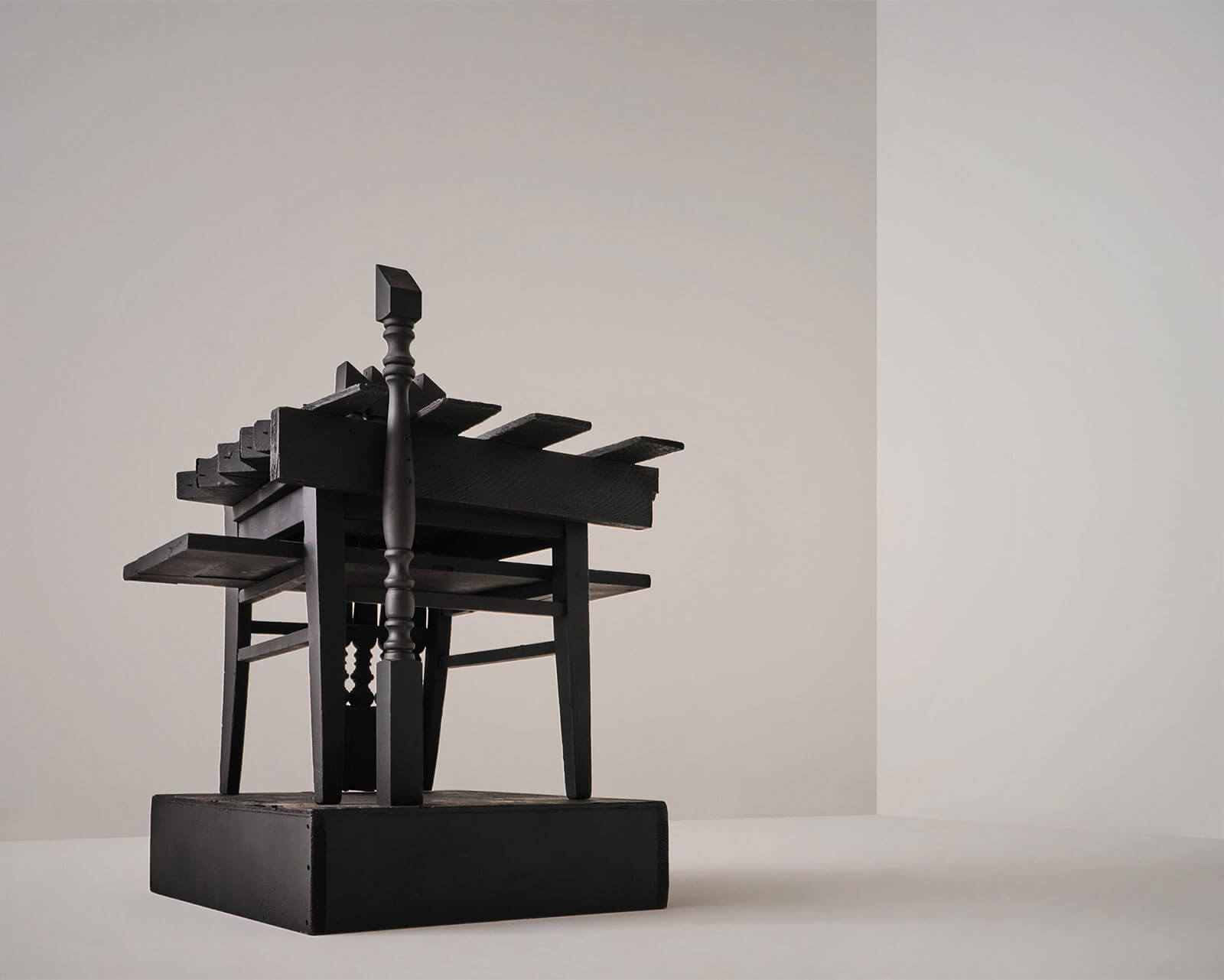

NK: What can you tell me about the chair by Louise Nevelson, who I know as a sculptor?

DO: Louise Nevelson exhibited this room, ‘Mrs. N’s Palace”, at the Met [Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York]. And she wanted to put a chair in the room, because she wanted people to be able to sit and look. At the last minute the Met decided that they didn’t want the chair, so she gave it to her assistant, who, after her death, gave it to a dealer, where I got it from. A chair to view sculpture.

Louise Nevelson, ‘The Little Prince (Throne)’, 1977

COURTESY: Louise Nevelson & Carpenters Workshop Gallery

NK: With some of the designs and the different materials that evolved over the decades and the way that industry evolved … it really did change design. I think that’s a throughline in the show as well as the different materials the women work with and how they evolved their practice with new technologies and new materials. Is there anything that stands out that you think should be highlighted?

DO: There is the ‘Dondolo’ rocking chair by Franca Stagi, which is from the 1960s. It’s made from fibreglass and polyester. It’s very 1960s. Another example is the Maria Pergay ‘Ring Chair’ from the 1970s, which was actually designed in 1968. Stainless steel at that time was an industrial material that was used for more decorative things. It was the material of the moment.

Maria Pergay, ‘Chaise Anneau’, 1968

COURTESY:Maria Pergay & Carpenters Workshop Gallery

Or, if you look at Anna Castelli Ferrieri’s armchairs, they are made in plastic by Kartell (of which she was the founder). The 1980s was the plastic era. All of these pieces really show something about the technological and material advancements of that time.

Anna Castelli Ferrieri, ‘Poltrona 4814’, pair of lounge chairs, 1988

COURTESY: Anna Castelli Ferrieri & Carpenters Workshop Gallery

NK: What do you hope people can gain from the show, or what you hope to inspire?

DO: What I want the show to impart is not limited to what women did at that time. It’s really about how ambition shapes people’s lives and contribution, and the fact that “anything is possible”. There are so many books written about women designers – especially in the past two years. I don’t aspire to say anything more than that. It’s more about women as minorities. Women that really came with ambition. Women who never gave up. Women who didn’t accept the verdict of not being allowed to do. That’s what made them successful. There were no professionals, or dealers, believing in what they did and giving them opportunities. They didn’t have that, not even in the 1990s. This show is very much about somehow navigating in this world alone. Today you have galleries that take designers under their wing. You have a lot of design fairs, design weeks, design publications.

Elizabeth Garouste & Mattia Bonetti, ‘Collérettes’, 1986

COURTESY: Elizabeth Garouste & Mattia Bonetti & Carpenters Workshop Gallery

NK: Do you have any advice for women today, or hopes for women in industry?

DO: Being a designer is a great profession for women, but it’s also a profession where you never go on vacation. It’s about passion and building a career. You can never plan. Once you’ve opened one door you never know what the next door will open for you.

Elizabeth Garouste & Mattia Bonetti, ‘Collérettes’ (detail), 1986

COURTESY: Elizabeth Garouste & Mattia Bonetti & Carpenters Workshop Gallery

It is your life and you have to learn every single day. If there’s one day you don’t learn anything, you’ve lost something. History is the most important thing. For me, a designer who doesn’t know history has no chance.

The Female Voice in Modern Design: 1950 to 2000 at Carpenters Workshop Gallery, New York.