Vincenzo De Cotiis: Éternel

A collection that combines gravitas and beauty, through the language of cataclysm and the patina of decay.

Carpenters Workshop Gallery, New York

10th May – 15th September 2021

Installation view, ‘Éternel’

COURTESY: Carpenters Workshop Gallery

IN HIS CAPACITY as an architect, Vincenzo De Cotiis has specialised in interpretively restoring Roman palazzos. He is known for subtracting, removing modern additions and peeling away surface coverings to reveal the piebald ghosts of frescoes (“Any frescoes were good when they started to peel and flake off,” wrote Ernest Hemingway). In his capacity as a furniture designer, his expressively mottled and scarred surfaces are charged with the feeling of relics, things which have survived the cataclysms and damages of history, even if that history extends no further than his production process. When De Cotiis uses aluminum it looks like it has been extracted from the ground, melted and cast – it almost carries the smell of carbon vapours and the sear of flames into the room.

Vincenzo De Cotiis, ‘DC1915’, 2019

COURTESY: Carpenters Workshop Gallery

Italy has long been the West’s sourcebook for nostalgic beauty. When German architect Albert Speer formulated an aesthetic of romantically planned decay, he took the ruins of ancient Rome as his model. However, Speer’s neoclassical interpretations lost much appeal when, in 1945, the projected Thousand Year Reich for which he laboured came to an end.

By the 1970s, De Cotiis was a college student and Italy’s Memphis movement had begun battering neoclassicism’s reverence for the past with a urethane foam ram. The Memphis movement celebrated veneered laminates and industrial foams for their artificiality; they pilloried the past, recent and distant, with lewd satire and punk-rock attitude. During the same period and across the same peninsular geography Arte Povera, an emphatically non-identical twin movement, gained force. Arte Povera took materiality as it found it – in heaps of rubble and scorched debris, in haunted remnants of a history no longer glorified but instead painfully confronted. Memphis and Arte Povera, through opposite aesthetic impulses, countered the legacy of fascist neoclassicism.

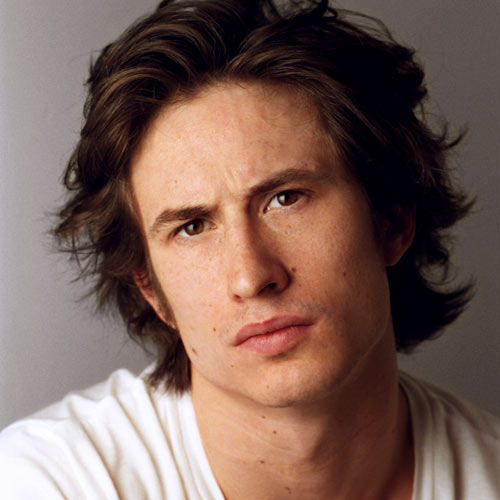

Vincenzo De Cotiis

COURTESY: Carpenters Workshop Gallery

So where does De Cotiis fit into this lineage? He looks to the past with a neoclassicist’s eye, while his forms are anything but. He is unyieldingly serious, unlike the Memphis designers. And he relishes the fine stone and glass work for which Italy is known – which Arte Povera artists rejected. There is, however, another difficult-to-place architect with whom his work resonates: Carlo Scarpa, whose Brion Cemetery, in San Vito d’Altivole near Treviso, Italy, a cipher of withholding mystery and alien gravity, delivers a quieting experience of suspended temporality. Scarpa was also known for exquisitely sensitive architectural interventions in historic buildings. In De Cotiis, Scarpa’s refined, precise, tectonics come together with the torn, melted and bandaged canvases, the ragged blown-to-bits assemblages of Arte Povera. He applies the language of cataclysm and the patina of decay to sensuous, even decadent materials; his pallet is charred, singed and abraded opulence. Interestingly he sometimes reverses this ordering as well – making rough and humble materials feel like gemstones.

Vincenzo De Cotiis, ‘DC1903’, 2019 (foreground); ‘DC1913’, 2019 (background)

COURTESY: Carpenters Workshop Gallery

One of De Cotiis’s most unexpected materials is fibreglass sourced from naval scrapyards. This may help to explain why such works as ‘DC1912A’ – an undulating cabinet that integrates iridescent cast aluminum, silvered brass and recycled fibreglass with coloured stucco – looks as though it was recovered from the deep of the Tyrrhenian sea, where time glides to the slow pulse of boneless medusozoa and the gentle drift of marine snow. Other pieces, such as the silvered brass ‘DC1913’, gleam with the firelight shadows of a Dantean underworld. ‘DC1914’, a coffee table, is a layered amalgamation of Brazilian granite, iridescent aluminum, and satin brass that can be visualised as a heterogenous hunk of Mies van der Rohe’s 1929 Barcelona pavilion ejected from a volcano. De Cotiis’s work is relentlessly glamorous and yet he manages to be lovely without being trite, lush without being gauche. The imposing gravity of his work also suggests that there is seriousness in explicit visual beauty and that beauty can itself be serious.

Vincenzo De Cotiis, ‘DC1909A’ light, 2019 and ‘DC1908’ table, 2019 (foreground); ‘DC1912A’ and ‘DC1912B’ cabinets, 2019 (background)

COURTESY: Carpenters Workshop Gallery

Oscar Wilde wrote that only superficial people do not judge by appearances. One must, looking at the work of De Cotiis, grapple with that proposition. Surely there is something wrong with such blatant, ravishing splendour? Surely there is something to condemn in the unrepentant pleasure of gleaming, unironic bronze layered extravagantly over slabs of rough stone? Or are such prejudices themselves an antiquated remnant of former aesthetic cycles?

Vincenzo De Cotiis, ‘DC1905’, 2019 (foreground); ‘DC1914’, 2019 (midground); ‘DC1915’, 2019 (background)

COURTESY: Carpenters Workshop Gallery

De Cotiis, who was born in Gonzaga and established his studio in Milan, has become one of the great living masters of romantic ruins. His ruins are situated in a very specific present. They reflect both the grandiosity of ancient architecture and, less romantically, the wars of the modern age – the obliterated firebombed cities, the piles of shoes, the pulverised scraps of daily life that became the oil paint of Arte Povera. Orpheus would disagree, but looking backward can be an excellent way to move forward. Because of the imaginative leaps required, attempting to resurrect the past sometimes leads to surprising, albeit unintended, innovations.

De Cotiis’s latest show, coming to Carpenter’s Workshop in New York City after a run in Paris, is titled ‘Éternal’. Its allegiances are as ancient as they are futuristic and it establishes him as one of the foremost contributors to what is, unfortunately, being called “collectible design,” a vital aesthetic movement that seems to have been named after an auction house catalogue. ‘Éternal’ is as connected to the history of Italian art as to the swift currents of contemporary design and if Oscar Wilde’s proposition is correct, this is work we would do well to judge by the pleasure in our eyes.

Vincenzo De Cotiis, ‘DC1919’, 2019 (foreground); ‘DC1914’, 2019 (midground);

COURTESY: Carpenters Workshop Gallery

Éternel at Carpenters Workshop Gallery