Weavers of the Clouds: Textile Arts of Peru

The intricacy and beauty of Peruvian textiles have been a source of inspiration for many – from designers such as Vivienne Westwood, to photographers and painters.

Fashion and Textile Museum, London

21st June – 8th September, 2019

EXPERTS HAVE LONG complained that the British Museum does not show enough of the pre-Columbian objects it inherited when the old Museum of Mankind closed. While it has a North American and a Central American gallery, there is a singular lack of a South American one – leading some to dub it the British Museum’s ‘lost continent’.

Now London’s Fashion and Textile Museum is able to give a tantalising glimpse of at least some of these holdings. Guest curator Hilary Simon has arranged the loan of 13 stunning Peruvian objects from the British Museum’s basement for this stimulating exhibition, augmented by pieces from Paul Hughes Fine Arts and Lima’s Museo de la Nación and Museo Nacional de la Cultura Peruana.

Tunic wearing ceramic, circa 500 AD

COURTESY: Paul Hughes Fine Art

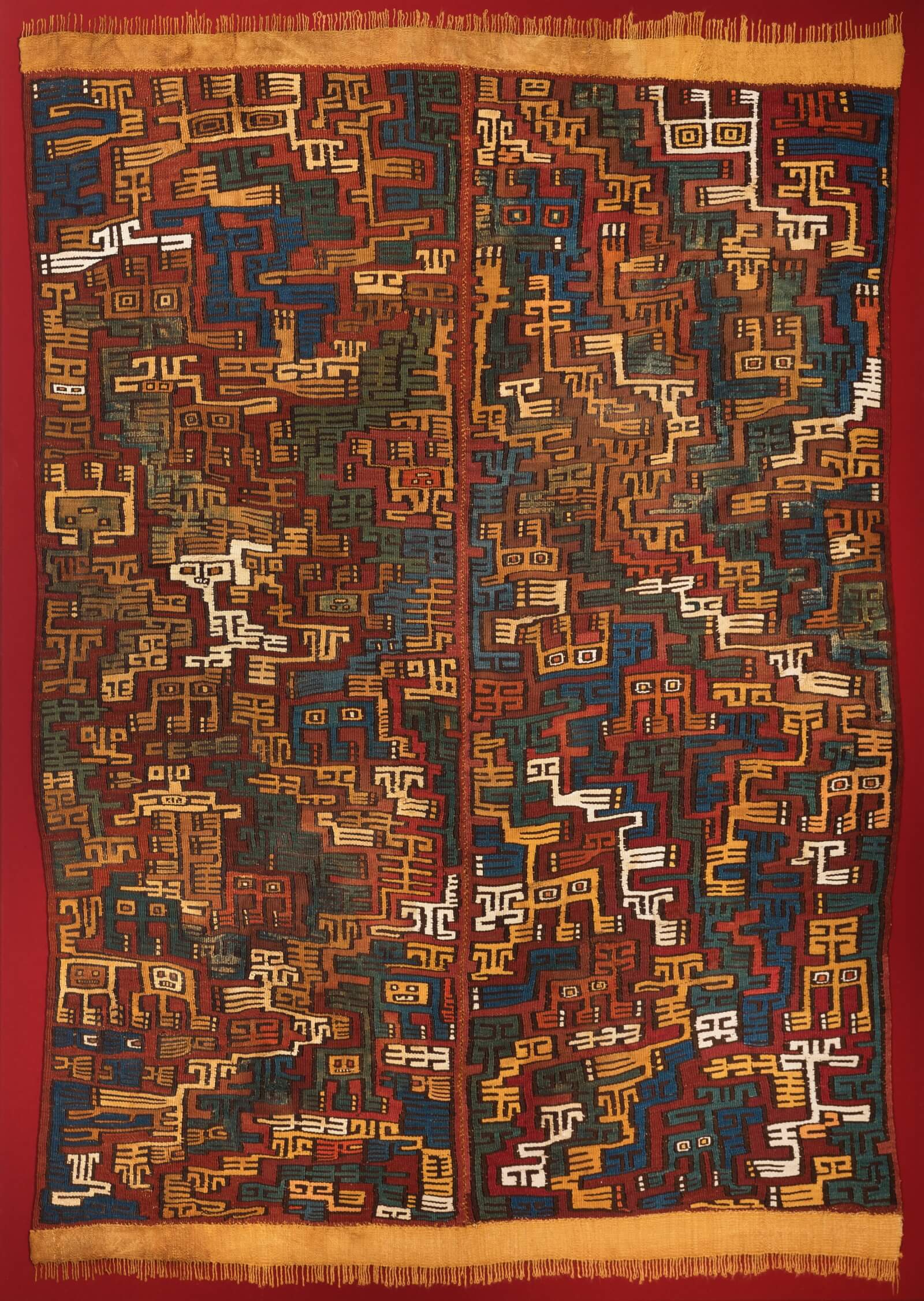

It is hard to chart five millennia of Peruvian culture since the first pyramids were built on the Pacific coast, but the exhibition makes a coherent case for how central weaving has always been to the pre-Columbian mindset. Using camelid fibre – usually llama or alpaca – as well as the feathers of small jungle birds like macaws, civilisations like the Nasca, Wari and later the Inca produced tunics and textiles of unusual complexity.

Perhaps the most moving object is a small wooden loom that has been preserved from the centuries immediately before the arrival of the Spanish. A partially woven textile with a pattern of felines is still on the loom, as if work was interrupted. When the conquistadors arrived in 1532, they could not understand why so many Inca warehouses were stocked with textiles rather than gold or silver, which the indigenous people considered less valuable.

Detail from a woman’s fiesta costume, Chumbivilcas, south Peru. Alpaca, sheep’s wool and acrylic, late twentieth century

COURTESY: Leonardo Arana Yampe / PHOTOGRAPH: © Fashion and Textile Museum

A new and fertile hybrid style of Peruvian textiles evolved from the sheep’s wool and the European styles of clothing the Spanish brought with them – particularly for hats, which the Quechua, the descendants of the Incas, liked to accessorise with Andean flowers and appliqué. A charming 19th century watercolour by Pancho Fierro illustrates the colonial fashion in Lima for the tapada: a long embroidered shawl draped around the body of a woman but also partially covering her face, leaving just one eye exposed – a tradition which may have come from persecuted Muslims fleeing Spain for Peru. In Lima, this freedom for women to move around the city relatively anonymously – and to flirt coquettishly from a partially covered face – was seen as so dangerous by the Catholic Church that they tried to ban it.

BY THE 20TH century, Peruvian writers and artists were reviving pre-Columbian traditions like traditional textiles as part of the indigenismo movement, just as was happening in Mexico. The exhibition includes an ambitious recreation of the Cusco studio of indigenista photographer Martín Chambi, who often photographed his subjects in traditional costumes. Only after his death did he achieve fame and a retrospective at MOMA for his extraordinary large plate glass negatives; during his life he was best known as a seller of postcards, some of which are included here.

Proto Nazca Tapestry, circa 300 AD

COURTESY: Paul Hughes Fine Art

More problematic perhaps is the inclusion of attempts by recent fashion photographers to appropriate Andean traditions. The glossy commodification of a highland culture that often operates at subsistence levels, can sit uneasily in the pages of Harper’s Bazaar.

One of the more unusual garments from the Amazon was designed by Vivienne Westwood in collaboration with the Ashaninka tribe, and shows uncharacteristic restraint – a Chanel-cut take on the tribal cushma tunic, with a hat and bag in soft greys; she says she responded in her work to the kindness and elegance of the tribe.

Vivienne Westwood, Autumn/Winter 2014/15 Gold Label show

COURTESY: Vivienne Westwood

Perhaps the most iconic of all the objects on display is that of an Inca quipu, the necklace of long knotted cords used by ancient Peruvians as a form of communication. A team of scholars at Harvard are still struggling to determine whether this was a form of language or, as seems more likely, merely a mnemonic aid for auditing storehouses in the Inca’s large empire.

But it is a reminder that ancient Peru was unique in not having any recognisable forms of writing or literature that correspond to the other great contemporary civilisations of the world. All their creativity was poured into different outlets and paramount among these was the tradition of weaving. In some fine contemporary examples from the Sacred Valley near Cusco, one can see how this tradition has continued and in recent years had a strong revival as community leaders like Nilda Callañaupa have encouraged the use of cochineal red and traditional motifs.

Women from the Huilloq and Patakancha communities in the Andean Highlands walking in the streets of Ollantaytambo

COURTESY: © Marta Tucci

Hilary Simon and the Fashion and Textile Museum are to be commended for the intelligence and diligence with which they have assembled such a rich show; as the exhibition has no illustrated catalogue, it needs to be seen in the flesh, or rather the garment.

Now all we need is for the British Museum to find the funding – and enthusiasm – to mount the long overdue major exhibition of Peruvian civilisation which London has lacked for so long. Or at the very least get a few more such objects out of its basement.

Fashion and Textile Museum – a contemporary fashion museum in Bermondsey, London.