Materiality and Poetry

Anne Bony explores the developing dialogue between French craft and contemporary design.

Karen Gossart, ‘Danse Tête bêche’, 2020

COURTESY: Sinople Gallery / PHOTOGRAPH: @Anthony Girardi

A YEAR OF enforced isolation and the experience of a less frenetic pace of life have inspired many of us to seek out a new relationship with time. Ahead of us on that journey are the many artists and designers who, through the painstaking use of craft processes, embed time as a value within the objects they make. In addition, through their explorations of different natural materials, they remind us that we too belong to nature, and that both time and nature are critical ingredients in the creation of meaningful objects.

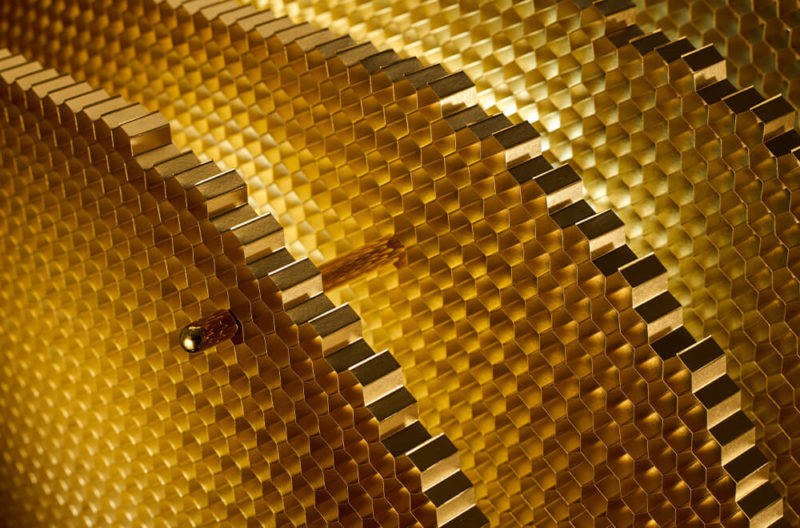

Denis Castaing, ‘Lampe Carrousel’, 2019

COURTESY: Denis Castaing / PHOTOGRAPH: Pascal Vangysel

The Arts and Crafts movement in the 19th century developed in rebellion against industry. In our contemporary art and design world, the primary importance of craft is less often championed. Sinople, a studio and gallery based in Paris, is determined to change that – to bring craft back to the centre of our attention. Founded in 2018 by Eric-Sébastien Faure-Lagorce and Julien Strypsteen, Sinople showcases art, craft and design, choosing artists who mainly deal with natural materials – wood, fur, ceramic, mineral and glass.

Hugo Haas Studio & Atelier Chatersen, ‘Prototype’, 2020

COURTESY: Sinople Gallery / PHOTOGRAPH: @Anne-Sophie Auclerc

“Through their explorations of different natural materials, these designers remind us that we too belong to nature …

Hugo Haas Studio & Atelier Chatersen, ‘Prototype’, 2020 (detail)

COURTESY: Sinople Gallery / PHOTOGRAPH: @Anne-Sophie Auclerc

“… and that both time and nature are critical ingredients in the creation of meaningful objects”

Since its inauguration, the gallery has hosted two important exhibitions: ‘Paysage intérieur, collectible nature Act 1’ in 2019, and ‘Act 2’ in 2020. Each promoted different approaches to creativity. ‘Act 2’, for instance, was concerned more widely with the idea of space and landscape, and their impact on the creative imagination. The exhibition evoked the ‘cabinets of curiosities’ of the Italian renaissance – the aristocrat’s way of displaying his wealth, intelligence, and the extent of his travels, through objects. In this case, in 2020, each work offered an opportunity to tell a story about a specific creative adventure, as the poetry of nature was transformed, through handwork, into an object of universal beauty.

Marion Chopineau, ‘Nomads’, 2019

COURTESY: Sinople Gallery / PHOTOGRAPH: @Anthony Girardi

The textile designer, Marion Chopineau, for instance, created a series of sculpted landscapes out of animal fur, titled ‘Nomads’. Polyhèdre studio composed landscapes from clay, with an oriental aesthetic, mixing enamelled and raw surfaces, and Olivier Sévère revealed the inspiring beauty of natural stone through his work ‘Les Lames’. Most of the selected works focussed on the nature of materials, and blurred the line between art and design.

Olivier Sévère, ‘Lames’, 2020

COURTESY: Sinople Gallery / PHOTOGRAPH: @Anthony Girardi

Aurélien Gendras, a young gallerist based in the Marché Paul-Bert in Saint-Ouen, is as committed as Sinople. His unconditional love for ceramics, especially sandstone, can be traced directly to his heritage – his family has been working for generations in Saint-Amand-en-Puisaye, a well-known pottery village dating back to the Middle Ages. Gendras is passionate about the craft renewal of the 1950s and 60s, a movement spearheaded by the potter Bernard Leach in England and Shoji Hamada in Japan.

Maarten Stuer, ‘Tourbillon’, 2016

COURTESY: Maarten Stuer / PHOTOGRAPH: Pascal Vangysel

In France, this post-war renaissance of ceramic expression had its epicentre in the village of La Borne, where artists such as Elisabeth Jouilia, Robert Deblander and Yves and Monique Mohy, brought earthenware into the space of art. Gendras showcases contemporary ceramic works alongside vintage pieces, to encourage the reintroduction of ceramic furniture into homes.

Denis Castaing, ‘Lampe Nocta’, 2021

COURTESY: Denis Castaing / PHOTOGRAPH: Pascal Vangysel

Denis Castaing, for instance, creates functional sculptures – lights, mirrors and ceramic wall screens – with distinctive surface effects. Another ceramicist, Clémentine Dupré, who has participated in several residencies in Japan, has shifted her work towards architecture and sculptural expression. Her series such ‘T.A.R. 1-2-3-4’ and ‘Typology’ renew the traditional language of potters.

Clémentine Dupré, ‘Typologies’, 2018

COURTESY: Clémentine Dupré / PHOTOGRAPH: Anthony Girardi

Maarten Stuer, a Belgian sculptor who lives in France, is also part of Gendras’s stable. His stools and sculptures blur the boundary between art and functionality.

Maarten Stuer, ‘Stuul III’, 2021

COURTESY: Maarten Stuer / PHOTOGRAPH: Pascal Vangysel

In this era of globalisation, mass consumption and the waste of natural resources, some industrial designers, too, have been prompted to move away from manufacturing to explore their manual skills. Férreol Babin, is one such designer, who found his way to ceramics and wood work through industrial design, architecture and scenography.

Férreol Babin, ‘A warped bottle. Black coarse stoneware with crawling white glaze’, 2021

COURTESY: Férreol Babin

In 2016, he started carving a collection of sculptural wooden spoons and has continued the project to this day. “I free myself from function and utility,” he says about the craft process, “I disconnect my brain from my daily tasks.” He continues, “I need this freedom, to be the only master of my time, of my work. I have chosen the spoon as a very maternal object – round, soft, comfortable as the bowl – very intimate as you put it in your mouth. A sculptural object that you really want to hold in your hands.” As an admirer of Japanese craft philosophy, he states that perfection lies in imperfection.

Recent work by Férreol Babin

COURTESY: Férreol Babin

Babin is exhibiting in ‘A New Realism’ at Friedman Benda, New York, from 3rd June, along with eight other makers who, in the words of curator Glenn Adamson “draw on deep wells of artisanal skill”. As Adamson recognises, “This affords them a certain autonomy, a carved-out space of self-reliance. Their works, often realised through invented means, are thoroughly considered, from their base materiality to their eloquent surfaces.” Babin’s contribution to the show, ‘À LA DÉRIVE’ is a beautiful bench in chestnut wood, the simply curved natural base section, a carved out trunk, elegantly offset by a rounded dark wooden cushion, as if it were carved from the same tree’s interior, both bearing the marks of the chisel.

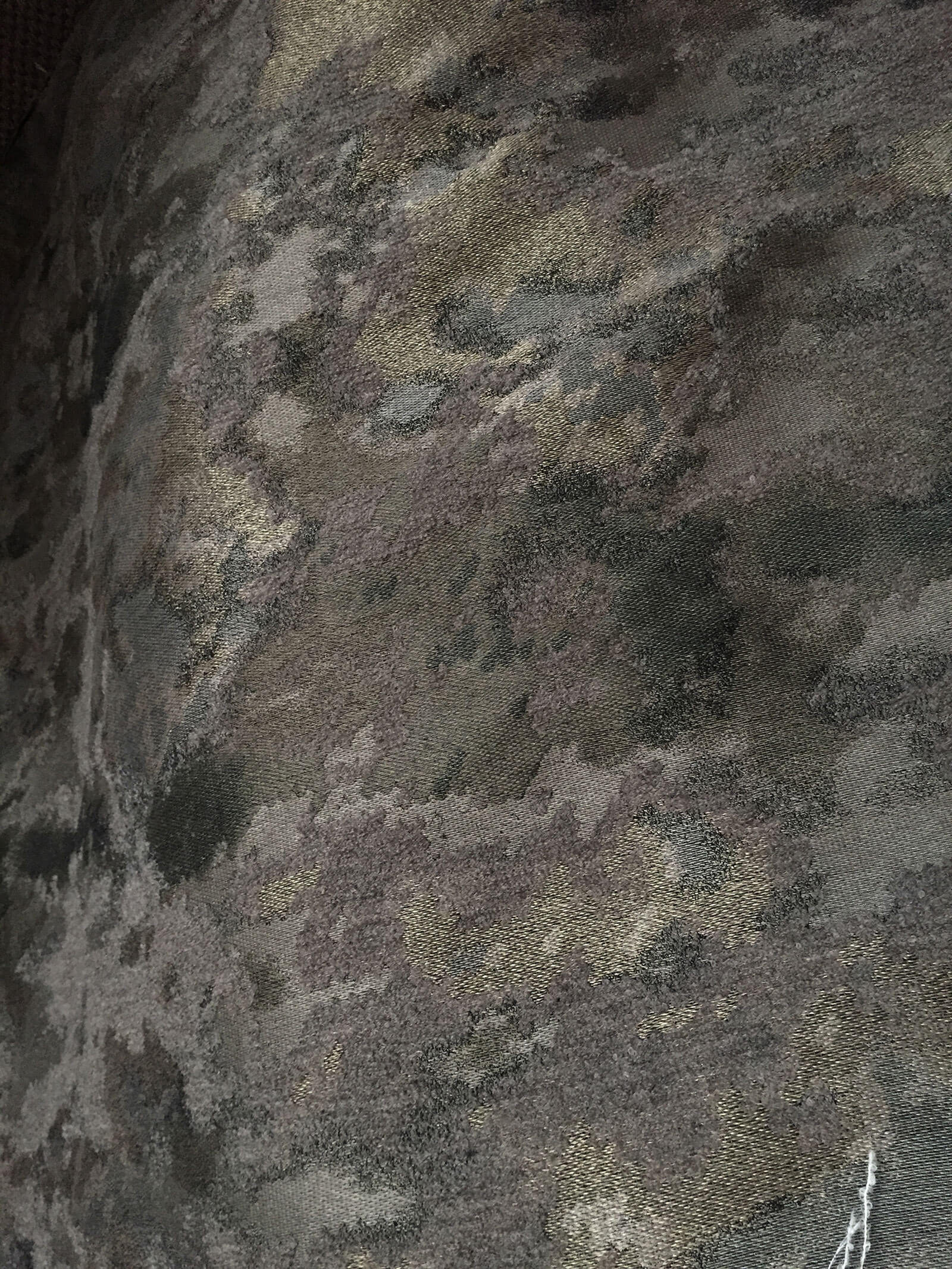

Benjamin Graindorge, ‘Nebulosus’ wallpaper, 2013

COURTESY: Benjamin Graindorge

Benjamin Graindorge, by contrast, has always been interested in forming connections between drawing and materiality – a difficult position to maintain in a school such as Ensci-Les Ateliers in Paris, focused on advanced studies in design. During his degree, Graindorge focused on the idea of meditation in poetic landscapes. Encouraged by the French designer Erwan Bouroullec, whose highly varied studio practice, with his brother Ronan, is grounded in drawing, Graindorge gradually found his own path.

YMER & MALTA/ Benjamin Graindorge, ‘Cloud In Chest’ cabinet, 2015

COURTESY: Benjamin Graindorge

His experimental approach seeks to trigger an emotional response in his audiences. He collaborated with Pierre Frey to produce the wallpaper ‘Nubem’ and the fabric ‘Storm’. At the gallery Ymer & Malta, he exhibited an iconic bench, ‘Fallen Tree’ (2011) and the same year ‘Hidden Skin’, a piece of furniture that had strong geometrical simplicity and sensuality. “I feel the poetry of things,” Graindorge reflects, “The truth of things is defined by materiality.”

Benjamin Graindorge, ‘Storm’ for Pierre Frey, 2016

COURTESY: Benjamin Graindorge

The French designer, Samuel Accocebery, meanwhile, has been inspired by collaborations with a range of different craftspeople. He treasures his residency at the Pôle Expérimental des Métiers d’Art in Nontron during which he met three craftsmen, learning and sharing the know-how of woodwork, ceramics and instrument making.

Samuel Accoceberry with craftsman Benoit Obé,

making ‘Wood+Wood’ console

COURTESY: Samuel Accoceberry / PHOTOGRAPH: © Bernard Dupuy

This immersive experience enabled him to gain some breathing space and perspective in his professional life.

Samuel Accoceberry, ‘Wood+Wood’ console, 2014

COURTESY: Samuel Accoceberry / PHOTOGRAPH: © Bernard Dupuy

As a result, in 2014, he worked with the company SAS Edition on ‘Wood-wood’, ‘Wool-wood’, ‘Porcelain-sandstone-wood’, all products grounded in materiality. Accocebery subsequently created a brand called SB26 with Bruce Cecere in 2020. Together, they pushed the boundaries of metal.

Samuel Accoceberry, ‘Lava’ console, 2019 (Edition SB26)

COURTESY: Samuel Accoceberry / PHOTOGRAPH: © Alexandre Delamadeleine

The result was textured and patinated furniture and lamps, such as ‘Rigel’, ‘Palma’, ‘Moon’ and ‘Lava’ that symbolise the metamorphosis of industrial iron into a masterpiece of sophistication: an alchemy of simple shapes and poetry.

Samuel Accoceberry, ‘Rigel’ lamp, 2020

COURTESY: Samuel Accoceberry / PHOTOGRAPH: © Alexandre Delamadeleine

These threads of craft philosophy, truth to materials, honed skill, a quest for authenticity and a reverence for time, are shared by many other designers. Noé Duchaufour-Lawrence, a French designer who has been trained in both sculpture and furniture design, and works across a wide range of materials, is among them. Now settled in Portugal he recently created a strand of work named ‘Made in situ’. As his Manifesto declares, ‘Made in Situ’ is “rooted in the treasures of a territory, its craftspeople and its systemic connections to nature.” Limited edition collections such as Barro Negro and Burnt Cork draw on specific local geographies, landscapes, materials and craft practices – whether the Barro Negro pottery from the Tondela region, or the widespread inventive use of cork sourced from the Algarve. Duchaufour-Lawrence’s definition of his current enterprise – a “searching back to basic principles, to the origins, to the ebb and flow of time ” – expresses a longing felt by many.

Atelier Polyhedre, ‘A Fleur d’eau’, 2020

COURTESY: Sinople Gallery / PHOTOGRAPH: @Anthony Girardi