Jacqueline Surdell

Inspired by the grids of Chicago, Catholic altars, the steel mills of Hegewisch and her career in volleyball, the artist weaves rope into huge textile works.

Jacqueline Surdell, ‘Earth Licker’, 2022

COURTESY: Jacqueline Surdell & Library Street Collective

ON SATURDAY 12TH March, Chicagoan artist Jacqueline Surdell opened a new show in Detroit, ‘Asymmetry’, showing large scale textile pieces, alongside artist Robert Moreland. Although she defines herself as a painter, Surdell’s work is rooted in the industrial history of her home city, with its blast furnaces, melting pits and manual labour. Building her wall sculptures is physically demanding, employing her body as a weaving shuttle, carrying kilos of industrial weft in and out of the warp, and her hand as a brushstroke. While her works honour industrial labour, they allow Surdell to explore social, cultural and spiritual ideas.

Jacqueline Surdell in her studio

COURTESY: Jacqueline Surdell / PHOTOGRAPH: PD Rearick

The Design Edit (TDE): How many pieces have you produced for this show?

Jacqueline Surdell: Three. I’m sharing the show with Robert [Moreland], whose work is more about colour field painting – it’s quite subdued – and I didn’t want to overwhelm the space with my pieces, as they are very intense and energetic. The number three was also important as I was rethinking my Catholic upbringing; trying to understand where I am with thinking about a great creator, so the idea of a trinity made a lot of sense to me.

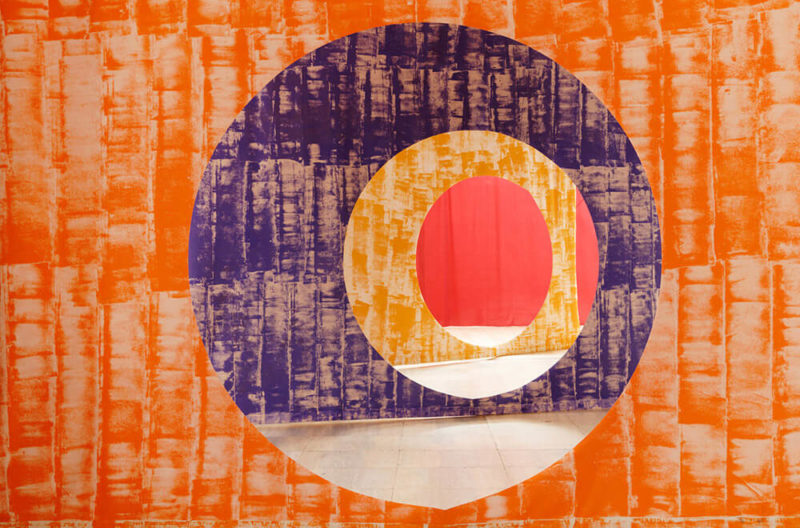

Installation views, ‘Asymmetry’

COURTESY: Library Street Collective / PHOTOGRAPH: PD Rearick

TDE: What led you to want to explore fibre?

Jacqueline Surdell: Firstly, my grandmother is a landscape painter. She emigrated from Amsterdam to Toronto after WWII and now lives in South Carolina. I have these very lovely memories of plein air painting with her. I’ve always been a painter and thought of it as a way to connect with the landscape and with the generations before me. So I came to fibre, macrame and weaving from a painterly perspective. I was thinking about it as an undulation of the canvas and how I could use cotton rope to expand upon the woven canvas.

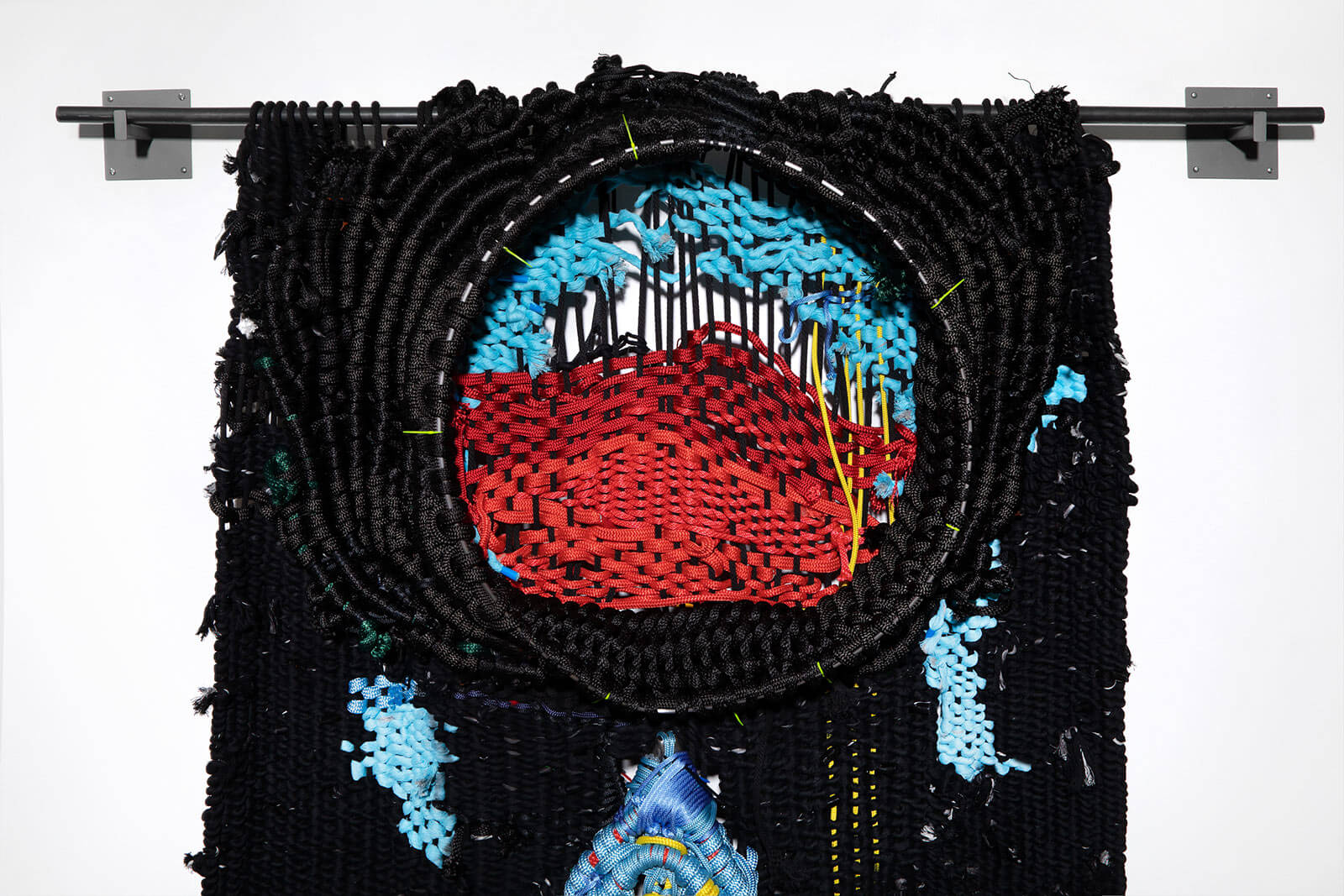

Jacqueline Surdell, ‘Not one but two either (blue)’, 2022 (detail)

COURTESY: Jacqueline Surdell / PHOTOGRAPH: PD Rearick

Secondly, I used to be an athlete. The first place I was truly happy was on the volleyball court, surrounded by strong women, doing what I imagined was for the greater good – to win. I played year-round competitively and then was recruited to play for Occidental College in Los Angeles. When I arrived, I was told that, like every athlete, I’d probably not be able to play much longer. It was one of those reality checks. So I went back into the studio to see what could come of all the things I’d learnt – endurance, discipline and an understanding of my body in space. I wanted to see if there was a way that I could turn that into a painting. I was painting these charcoal landscapes and I was trying to engage my body with the canvas in a way that the Abstract Expressionists, Mark Bradford, people like that paint … but it just wasn’t working. I couldn’t figure out a way to engage repetition – something that is fundamental in my sports work, as well as in my work now – this idea of doing the same thing over and over and over in order basically to try and achieve perfection in an almost ritualistic way.

Jacqueline Surdell, ‘Not one but two either (red)’, 2022 (detail)

COURTESY: Jacqueline Surdell / PHOTOGRAPH: PD Rearick

But when I found rope, I found it amazing because it reminded me so much of my own body. I was never a really big person, or really strong. I was a smart player, kind of scrappy. And rope has the same kind of underdog quality that I can’t help but appreciate.

You can roll it up and then take it out – and it can hold thousands of pounds in weight. I thought it was such a female strength: “I’m just going to do my job, I don’t need all the attention, I hold things up, I hold things together, I break my body to create life”. I had never thought about this before or questioned the way I thought about strength. At the same time as I found this material, I was looking at the work of Faith Wilding, Harmony Hammond, Mrinalini Mukherjee – iconic feminist artists who were using textile to question gender binaries and things like that.

I went back to the studio and I took a canvas stretcher bar and made a loom out of it and started collaging and weaving macrame with it. Then I went to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, the Fiber and Material Studies department, and actually learnt how to weave. At the same time, I delved into the history and ideas of division of labour. After exploring different art forms at Occidental, I wanted to come back to a formal art and I found this yachting cord with these incredible colours.

Jacqueline Surdell with ‘Earth Licker’ in progress, 2022

COURTESY: Jacqueline Surdell & Library Street Collective

TDE: Are there any other critical sources of information for you? You were in LA and now back in Chicago. Is there inspiration from the city, other aspects of your family history? Politics? The women artists you are inspired by? Athletic movement?

Jacqueline Surdell: The grid of Chicago is a huge influence. I grew up in a grid and there’s some appreciation for that level of control. When I talk about endurance and discipline, it’s really about control. Making rules for myself. For instance, all these new works are primary colours and primary shapes: that was an arbitrary rule that I made for myself, as I wanted to see what I could do within that sphere. Sport always teaches you “What are the rules and what are the ways in which you can work with them.” I’ve always found it really creative and interesting, how the different coaches and players engage with those rules and constructs.

Installation views, ‘Asymmetry’

COURTESY: Library Street Collective / PHOTOGRAPH: PD Rearick

Coming back to my family, I’m a third-generation Chicagoan on my dad’s side. He grew up in a Polish neighbourhood on the south side of Chicago and my grandfather worked in the Hegewisch steel mills his whole life. When I was younger he fell at work, shattering his leg, and they put steel rods in his leg. In my mind, it was like “You make steel, and steel heals you.” I had a curious understanding of material and labour and thought that made complete sense. My work hangs on steel rods and there are steel pieces within these newer pieces, like steel circles. These offer a formal perspective, but in addition, conceptually, there is something that is a little mid-west gritty about the work. It’s really heavy and industrial looking.

Jacqueline Surdell, ‘Not one but two either (blue)’, 2022 (detail)

COURTESY: Jacqueline Surdell / PHOTOGRAPH: PD Rearick

TDE: And I think you are interested in the work of Magdalena Abakanowicz, the Polish fibre artist and sculptor?

Jacqueline Surdell: I was particularly taken with her woven wall works and screens – made from rough materials found by the docks of the Vistula River. I was fascinated and really excited by the process of art making as a way to work through complex human dynamics, such as, for her, the trauma of WWII and the fate of Poland. I was very taken by that work specifically.

TDE: Did you have to build the loom yourself?

Jacqueline Surdell: Yes, and that’s why I say I’m making line into form – because I create these looms and build from there, and it’s all raw material until I get to play with it.

Installation views, ‘Asymmetry’

COURTESY: Library Street Collective / PHOTOGRAPH: PD Rearick

TDE: You set yourself these parameters, primary colours and primary form, for this particular show. And the triptych – you’ve taken a very primary concept – can you suggest why?

Jacqueline Surdell: I was challenged by the scale in that gallery – it’s a massive space, and I really had a feeling of the sublime. The same feeling I’ve had when I walk into churches and amphitheatres; those places where you feel part of something larger, but also really small and individual. I thought I had to make an altar, or something like that. I’m reading Roland Barthes’s Mythologies and I was wondering why altars have become a sign, signal and a meaning of a holy place. I wanted to engage in that conversation. So I went with circles and triangles, very primary shapes.

Jacqueline Surdell, ‘Earth Licker’, 2022 (detail)

COURTESY: Jacqueline Surdell & Library Street Collective

TDE: Your work seems to be on more of an architectural scale than a domestic one. They appear to be inspired by the opportunity to occupy certain specific spaces. Have you thought about the ongoing life of the pieces?

Jacqueline Surdell: I just want to let the works talk and they end up huge! It is my work and I’m in control but I really feel like each one has such a voice on its own. But I also got into this whole line of work through installation. At Occidental I had this awesome professor Mary Beth Heffernan, who is an artist, and she would say, “Think about space, engage with space.” And this made immediate sense to me – again, think about the volleyball court – this idea of understanding my body in space and reacting to things around me, well that is basically how I grew up. Although I talk about these works as paintings they have an inherent sculptural quality. And they are also influenced by my reach. Why am I obsessed with works eight feet high or six feet wide? That is my reach!

Robert Moreland and Jacqueline Surdell: Asymmetry at the Library Street Collective runs from 12th March – 4th May, 2022.