Zeev Aram

The man who perceived 1960's Great Britain to be "a modern furniture desert" and then set about transforming it.

We were very sorry to hear of the death last week of Zeev Aram, the much-admired and influential founder and chairman of Aram Designs Ltd. In his honour, we are pleased to be able to run this edited version of an essay by collectible design specialist Michael McCollum.

Zeev Aram

COURTESY: Aram Designs Ltd.

ZEEV ARAM’S CAREER as a designer, commissioner and most notably retailer of modern design spanned six decades. He opened his first enterprise, a showroom and interior design practice, on the King’s Road in Chelsea in 1964, and the most recent incarnation of his vision – the ARAM store and Aram Gallery on Drury Lane, completed in 2002 – still flourishes. In the intervening years, the appreciation of modern and contemporary design by the British public has changed radically – a development influenced in part by Aram’s introduction of a number of pieces to the UK market that are, indisputably, iconic additions to the design lexicon.

Eileen Gray, ‘Bibendum’, 1926

COURTESY: Aram Designs Ltd.

An unlikely person to have become a British design impresario, Aram began a career in the Israeli navy, then came to London in the late 1950s to study interior and furniture design at the Central School of Art and Design. On graduating, he worked with Ernö Goldfinger, Sir Basil Spence and Andrew Renton before establishing Zeev Aram and Associates interior designers and Zeev Aram Designs Ltd furniture showroom in 1964 at the age of 33. It was dissatisfaction with what was available as a young designer that prompted Aram to open the shop alongside his design business. Aram recalls at the time that only the odd pieces of Eames were available, that the UK was, in his words, “a modern furniture desert”.

Aram Store, Covent Garden

COURTESY: Aram Designs Ltd.

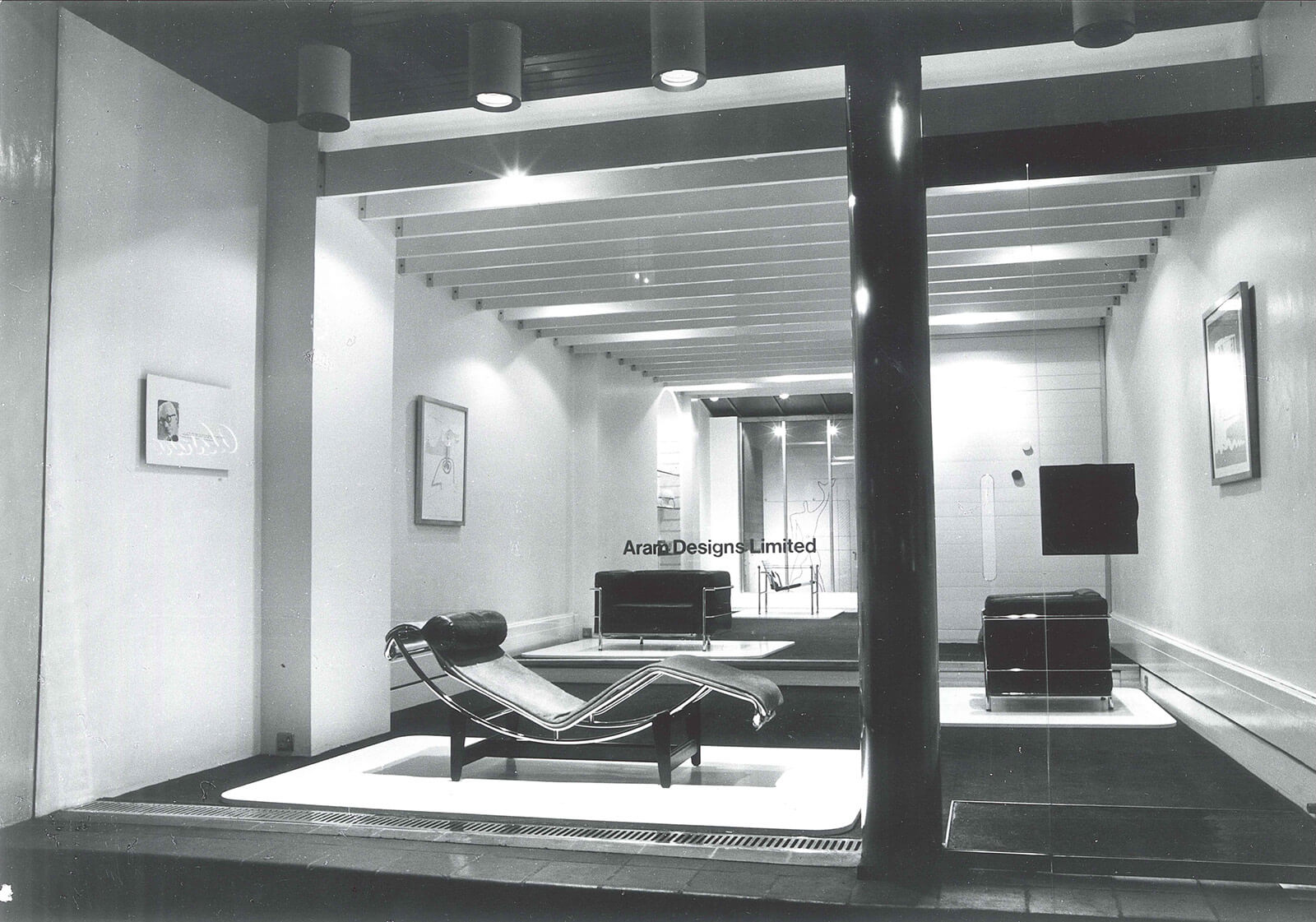

To redress this Aram energetically pursued the rights to Marcel Breuer’s tubular steel furniture, introducing the pieces to the UK market at his shop, where they accompanied some of his own designs. In 1966, Le Corbusier’s and Charlotte Perriand’s 1920s classics were added to the retail selection. At this point their furniture was being produced in tiny quantities in Paris workshops – Aram was at the forefront of initiating a more ambitious level of manufacture. Aram also introduced contemporary Italian design to the UK market in the mid-1960s, including furniture by Vico Magistretti, Carlo Scarpa and the Castiglioni brothers, while in 1968 he introduced Hans Coray’s perforated aluminium ‘Landi’ chair. It is now produced by Zanotta, renamed the ‘Spartana’.

The ARAM showroom preceded the opening of Terence Conran’s Habitat, situated just a few hundred yards away, by several months. It was of course much smaller, dealing exclusively in furniture and lighting in comparison to the comprehensive selection of homeware sold in Habitat. The showroom had previously been a restaurant, but Aram transformed the space into a stark, minimalist interior with large uninterrupted glass windows to display the furniture. It was important to Aram that these pieces were as conspicuous as possible and the white interior was constructed to allow a clear view of the entire shop; the showroom featured a mezzanine floor and tubular steel railings to complement the reproductions sold.

Aram Designs Limited showroom, Kings Road, 1964

COURTESY: Aram Designs Ltd.

While pop culture, exuberance of colour and period revivalism were all the rage, Aram’s stark merchandise and setting countered the counter-culture. The designer would stand outside listening to the comments of passers-by. The shop was regarded as ‘clinical’, and people wondered why anyone would want to buy ‘hospital furniture’. Even while receiving hate mail, he judged no publicity to be worse than no publicity; his biggest fear was that “people would just walk past”.

Aram Store, Covent Garden

COURTESY: Aram Designs Ltd. / PHOTOGRAPH: Veerle Evans

Rising rents, the need for more space and a changing zeitgeist led Aram to close the Kings Road showroom in 1973 and move the business to Covent Garden. From here, in 1975, he made the bold decision to bring the long forgotten designs of Eileen Gray out of obscurity and into the marketplace. Aram met Gray and, after long discussions, won her confidence and the exclusive licence to manufacture her designs for the first time in factory, rather than workshop, numbers.

Eileen Gray, ‘Non-conformist’ chair, 1926 and ‘Tube’ lamp, 1927

COURTESY: Aram Designs Ltd.

This proved challenging. Relying partly on Gray’s memory, contemporary photographs and appeals published in French newspapers for owners of the handful of the original pieces to come forward, reproductions were made as faithfully to the originals as possible. Designs were chosen on the basis of their universal and timeless quality. The ‘Bibendum’ chair, ‘Lota’ sofa and ‘E1027’ side table were among the pieces put into production, while the more overtly crafted ‘Transat’ chair was thought less suitable.

Eileen Gray, ‘Blue Marine’ rug, circa 1920-1930

COURTESY: Aram Designs Ltd.

This collaboration undoubtedly catalysed the subsequent appreciation and revival of Gray’s work culminating in an exhibition at the Victoria & Albert Museum three years after the death of the designer in 1979, which later travelled to the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Eileen Gray, ‘Brick Screen’, 1922 -1925

COURTESY: Aram Designs Ltd.

But Aram did not focus on Gray alone. Expanding his business into an adjoining premises, he built his showroom into a family-run, destination store, concentrating on lighting and furniture. Added to the inventory were pieces from brands including Artek, Knoll, Vitra, Flexform, Cassina, Porro, and Moroso – often sold exclusively and for the first time, consistent with earlier offerings.

Aram Store, Covent Garden

COURTESY: Aram Designs Ltd. / PHOTOGRAPH: Veerle Evans

Aram was also committed to the discovery and promotion of new work. Each September from 1988 to 1994 he organised and funded an exhibition to promote the work of young designers and graduates representing all areas of the applied arts, selected from graduate shows across the UK. The express intention of these initiatives was to bridge the divide between designers and manufacturers. It was on seeing Jasper Morrison’s ‘Thinking Man’s Chair’ at the Aram show of 1986, for instance, that Giulio Cappellini decided to undertake its production.

Aram Store, Covent Garden

COURTESY: Aram Designs Ltd. / PHOTOGRAPH: Veerle Evans

In 2002, Aram, together with founding curator Daniel Charny, established The Aram Gallery, located on the fourth floor of the Aram building, where he supported five shows a year of “experimental or new design”, some from designers – such as Martino Gamper – at the very beginning of their careers. Other exhibitions included a career retrospective of Achille Castiglioni featuring furniture from Zeev Aram’s private collection, a guest-curated exhibition on colour in design by textile designer Ptolemy Mann, and an exhibition of contemporary Spanish design in collaboration with the Spanish Embassy. Aram believed that design should ultimately strive towards engagement with industry and manufacturing – but as opportunities for large-scale production have declined, so he also contributed to the rise of limited-edition design, by drawing attention to the wilder, experimental and less functional edge of contemporary design practice.

Aram Store, Covent Garden

COURTESY: Aram Designs Ltd. / PHOTOGRAPH: Paul Raeside

Zeev Aram’s role in retailing and promoting design in Britain is often overlooked in comparison with his better-known peer Terence Conran. While Conran sought to create a lifestyle business and operated on a large scale at inception, before branching into unrelated ventures, Aram had a different ambition. He quietly tasking himself with discovering and reviving a broad array of leading manufactured design – most of which is now ubiquitous in the ‘designer’ interior landscape. This was often realised in part without commercial gain (notably Gray’s work), and importantly as Aram would remonstrate, without the support of the powerful industry associations and trade bodies that facilitated the cultivation of new design (as exist in Italy or France).

Still very much relevant, the Aram brand early on was mostly identified with the design cognoscenti, architects and contract buyers. It continues to broaden, reaching a more design literate clientele that it played a part in creating. Zeev Aram was awarded an OBE for services to design and architecture in 2014 and the ADI Compasso d’Oro XXV for Lifetime Achievement in 2018.

Zeev Aram

COURTESY: Aram Designs Ltd. / PHOTOGRAPH: Ivan Jones