Christopher Kurtz

As his show opens at Messums Wiltshire, Charlotte Abrahams explores Kurtz’s approach to sculpture and the inspiration for his new large-scale displays.

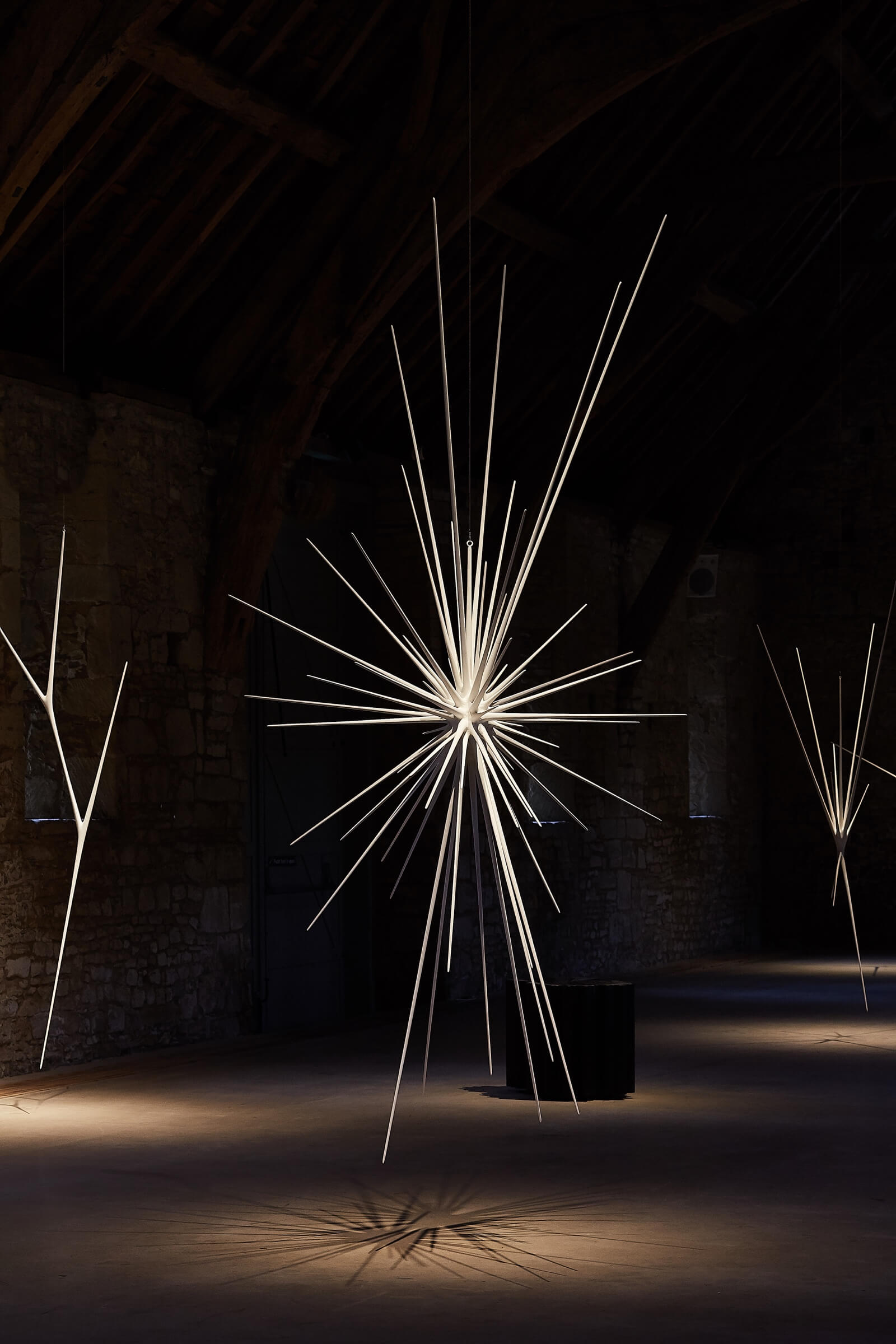

THIS SUMMER, THE vast, ancient tithe barn of Messums Wiltshire plays host to 12 new works by the artist Christopher Kurtz. The nine suspended constellations, each composed of limbs of linden wood so slim that they challenge the tensile strength of the material, are set against three short benches, each placed to frame the view and provide visitors with a moment of repose. Titled ‘The Traveller cannot see North but knows the Needle Can’, the show is both a direct response to the history and specific location of the barn and a celebration of the poetry to be found when craftsmanship and artistry collide. Charlotte Abrahams spoke to Kurtz at his studio in the Hudson Valley.

Christopher Kurtz in his studio

COURTESY: Messums Wiltshire / PHOTOGRAPH: © Kate Orne

CA: This exhibition is the result of an invitation to create a solo response to Messums’ 13th century barn. What made you say yes?

CK: When I first visited Messums Wiltshire a couple of years ago, I felt that the space and its geographical location close to Stonehenge were charged with a sense of history and deep time. I’d been dreaming of an opportunity to do a mature, large scale display using the form language I’ve been working with for the last ten years; this invitation provided that opportunity.

CA: The form language is familiar but the pieces are site specific?

CK: Yes, everything has been made for this show and is informed by the building and its place on the planet. The suspended mobiles are called Meridians and, while they don’t create a shaft of light on the solstice or anything specific like that, they are metaphors for that way of organising space.

Christopher Kurtz, ‘Wiltshire Meridian CK 40619, 7x 7y 8z’, 2019 (foreground)

COURTESY: Messums Wiltshire / PHOTOGRAPH: Iain Kemp

CA: And what about the title?

CK: It’s a slightly altered quote of Emily Dickinson, which I know is a major liberty to take but I changed ‘sailor’ to ‘traveller’ because I wanted to be more universal and a bit specific to the exhibition’s geographical location – Messums is on the chalk path from Wiltshire to Dover and the pilgrims who walked it were called Travellers. Also there are a lot of metaphorical sextants and navigational devices in the work, so the compass referred to in the quote is also an inner compass. That speaks a little to my belief that not knowing what a thing means shouldn’t stop you from making it.

Christopher Kurtz, ‘Wiltshire Meridian CK 40319, 7x 7y 11z’, 2019

COURTESY: Messums Wiltshire / PHOTOGRAPH: Iain Kemp

CA: That’s interesting – can you expand?

CK: When I was at art school, we were taught how to critique things and how to explain them and I struggled with that. Over time, I’ve become more comfortable with just letting the seed of interest advance a piece of work, and with not knowing what it’s about. That doesn’t mean the work is without meaning, it’s just that, for me, creating something and imposing meaning on it are things that don’t always happen at the same time. The way I work isn’t so didactic, in that I say ‘this is how I’m going to do it’. It’s a little bit more like playing, but it’s also deadly serious.

CA: You work in a very hands-on way, at the bench in your studio. Is that key to your work?

CK: Absolutely. I used hand tools because digital tools are way too abstract for me. I don’t start with ideas; I start with exploration so most of the way I find the form is through edge tools – spoke shaves, planes and chisels. My process is entirely based on working. I wish I had something more romantic to say, but it’s just about showing up at the workshop and doing it every day.

Christopher Kurtz’s workshop

COURTESY: Messums Wiltshire / PHOTOGRAPH: © Kate Orne

CA: That’s a very crafts-based approach. How important is the technique, the craftsmanship?

CK: I am really curious about woodworking and I love the technique, but I see it as just a tool to get to the artistic expression. Having the skill to do something doesn’t mean you should do it – sometimes doing less and letting the technique take a back seat to the motivation for making the work is a much more powerful approach. The first thing I want to pay attention to, both for myself and the viewer, is the sculptural impact of the piece – not the craft, the technical prowess or the workmanship. All of those things are sort of interesting to me, but not as interesting as the emotional impact. When someone looks at my work, I want the initial read to be about space and emotion and what it’s doing. The workmanship is something the viewer earns with closer inspection, much in the way I earned it.

CA: That’s an approach you share with the artist Martin Puryear

CK: Yes, I spent five years working with Martin when I left college, then went back to help him with his 2008 retrospective at MoMA. His influence has been so deep that I’m still finding out what it means to me. I left art school feeling a little unmoored from what had originally motivated me to be an artist – which was the objecthood of things – because the teaching was all very conceptual and post-studio in the nineties. I knew I wanted to work with someone who was speaking the language I wanted to learn so, rather than go to graduate school, I cold-called Martin. He is someone who is highly relevant in the contemporary art world but has never let go of hand craft and the love of objects.

Christopher Kurtz, ‘Wiltshire Meridian CK 40219, 4x 1y 10z’, 2019

COURTESY: Messums Wiltshire / PHOTOGRAPH: Iain Kemp

CA: I’m interested in this idea of the ‘objecthood of things’

CK: For me making sculpture is not a conceptual or immaterial practice, it’s physical. I settled on wood as my medium because it’s structural, but also malleable and alive. I even regard painting the sculptures as a material rather than an ornamental process. The milk paint I’ve used on the Messums’ Meridians, for example, is made from calcium carbonate mixed with protein. The burnished graphite on the top of the benches isn’t just sprayed on, it’s compressed into the fibres of the wood. These are materials and applying them is another layer of sculptural action.

CA: Painting the wood also conceals it, which makes looking at it rather an odd experience – your work speaks very eloquently of wood but it also makes the viewer question what the material is.

CK: Thank you for that, it’s a quality I enjoy and when I’m able to strike that chord, I feel that I’ve succeeded. One of the things I like about wood is that its structure imposes rules and limitations and that gives me something to push against. I’m excited by the idea that I can test the limits of those rules, making the material do something it’s not supposed to do, like bend or curl. The reason I find people’s uncertainty about the material successful is because it makes them slow down and look harder. We like to categorise things, but if we’re not sure what we’re seeing then we have to spend more time looking. The benches still read as wood, but the burnished graphite also makes you wonder whether they’re metal, or paint or a ceramic glaze. I think the eye likes to be delighted by things it finds appealing but doesn’t understand.

Christopher Kurtz, ‘Wiltshire Meridian CK 40919, 11x 3y 3z’, 2019 (foreground); ‘Black Hole Bench CK 60119, 1.4x 1.6y 1.8z’, 2019 (background)

COURTESY: Messums Wiltshire / PHOTOGRAPH: Iain Kemp

CA: You use many different varieties of wood – the Meridian sculptures are made from linden wood for example. What drives that choice?

CK: The choice of wood species is not an ornamental decision; the material has to serve the form. I’ve used linden wood for the Meridians because it’s easy to carve and has these very soft fibres which allow me to create attenuated spikes. If I’m doing a work-a-day stool, I need to use white oak, if I’m ebonising then I need to used woods that are high in tannins, like walnut or oak. I think of it more like engineering – some things just exist for poetry and some things have to perform a structural task.

CA: Structure – the methods of how objects are designed and built – seems to be an ongoing area of interest. You’ve described sculpture as ‘a protest against gravity’ – what do you mean by that?

CK: Ha! That sounds a little pompous but, as a sculptor, the question of how to make something stand up is one I’m mitigating constantly. Even when the work is suspended it’s a balancing scale – a little bit more weight on this side will change the posture of the piece. That’s the practical side, but making something stand up is also a way of affirming that we exist – as soon as you stick something up, it casts a shadow, like Stonehenge, so for me, sculpture is just a way of trying to organise the world. It’s a very simple gesture, but it’s the fundamental gesture of how we make our way in the world.

CA: I’m curious that you’ve used the word posture – do you see your sculptures as figures in some way?

Christopher Kurtz, ‘Wiltshire Meridian CK 40819, 6x 4y 7z’, 2019

COURTESY: Messums Wiltshire / PHOTOGRAPH: Iain Kemp

CK: Yes. In classical ballet, there’s a gesture called ‘allongé’ where the dancer extends a limb to elongate a space, and I’ve tried to do that with the mobiles at Messums. I want these attenuated points to suggest different scales – they can look like celestial events in the way Glenn Adamson writes about in the catalogue [link below], or go micro and be like cell-structures – but at the end of the day, the way I want people to interact with them is on a human scale. The way we interact with the world is through our bodies, our hands and feet, and so I wanted the pieces to read a little like figures too. That’s another reason the hand-making is important – these sculptures are made by people (me and my two wonderful assistants). I’m a little awkward in my body, but when I work in the studio I feel graceful and the sculptures are a record of that.

‘The Traveller cannot see North but Knows the Needle can’ runs from 13th July – 1st September at Messums Wiltshire, Place Farm, Court Street, Tisbury, Wiltshire. Prices range from £8,000 – £22,000.

Catalogue Essay by Glenn Adamson