African Design

Using a range of local materials – from recycled metal and coconut palms to canoes – and collaborating with local craftspeople, contemporary African designers are attracting international interest.

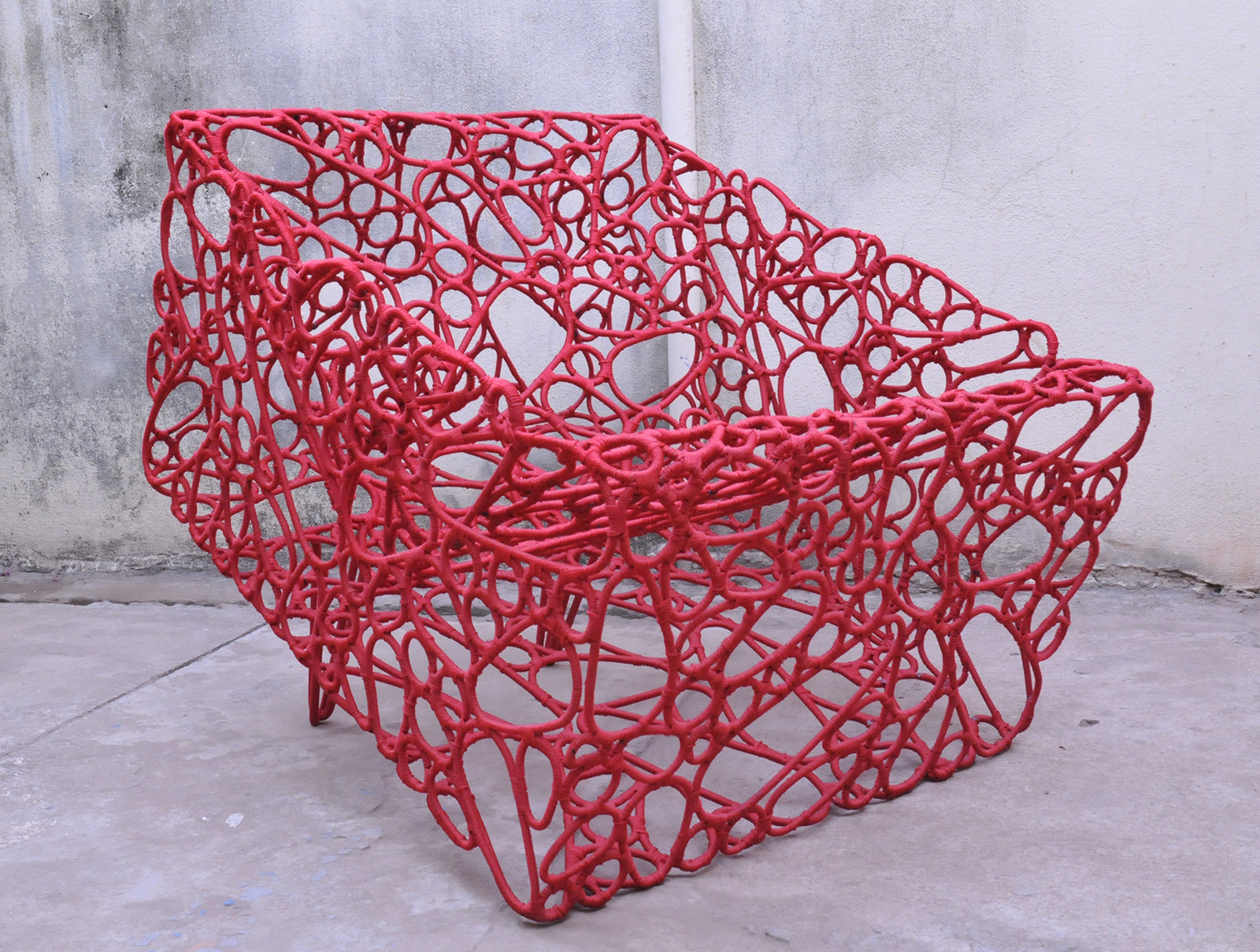

Cheick Diallo, ‘Samsa’ lounge chair, 2011

COURTESY: Cheick Diallo

THE PALAIS DE Lomé, a new cultural venue in Togo, was inaugurated in December with an exhibition paying tribute to Kossi Aguessy, the visionary artist/designer of Togolese descent. In the renovated waterfront palace, which was constructed in 1905 and formerly served as the German, then French, governors’ residence, a diversity of Aguessy’s pieces are on display. Titled ‘Kossi Aguessy: Infinity (1977-2017)’, the retrospective pinpoints the breadth of his output, subtly blending African influences and western production methods, from industrial design to sculptures and paintings. It positions him as a reference for Togo’s upcoming generation at a time when contemporary African design generally is garnering increased attention globally.

Born in Togo as Kossigan Baaba-Thundé Hervé Aguessy, Aguessy studied industrial and interior design at Central St Martins in London, worked for Philippe Starck and then set up his own Parisian studio in 2008. His ‘Jord’ chair (2012), made from rhythmically layering pieces of oak, and ‘Fogo’ lamp (2012), with organic light-emitting diodes at the tips of its branches, are in the Centre Pompidou’s collection.

When Sonia Lawson, director of the Palais de Lomé, conceived the idea for a design gallery, she thought of involving Aguessy in some capacity. The news of his untimely death on his fortieth birthday – Aguessy ended his life after battling cancer – prompted her to invite the curator Sandra Agbessi to assemble a show celebrating his multi-faceted work.

Kossi Aguessy, ‘The Stool’, 2014-16

PHOTOGRAPH: Joel Vogt

The exhibition is named after Aguessy’s scarlet ‘Infinity’ chair (2016), made from looping aluminium into a deformed figure of eight, the lower part serving as the base, the upper part as the seat. What emerges is his sculptural and technical wizardry for mastering materials. This is discernible in the bronze, honeycomb-like fruit bowls (2008-2010); the sumptuous ‘Fjord’ armchair in Carrara marble (2010); ‘The Stool’ (2014-2016), a brass stool made with graceful simplicity; and smooth ceramic masks (2010-2016) that reinterpret traditional African masks. Hugely curious about processes, Aguessy covered his stainless steel, prismatic-shaped, totemic chair, ‘Useless Tool’ (2008), with a low-reflective material used in aviation.

Kossi Aguessy, ‘Infinity’ armchair, 2016

PHOTOGRAPH: Joel Vogt

“It was obvious and logical to present an exhibition on Kossi, who achieved in a couple of decades what some designers don’t achieve in a lifetime,” Agbessi says. “When you encounter his work, you doesn’t necessarily think of Africa. Apart from the masks, the reference to Africa is extremely subtle – such as the brass sceptre that he made for the Musée de la Récade in Benin for which he revisited an African form to make an object of design.”

Earlier this year in Dakar, meanwhile, Galerie Cécile Fakhoury juxtaposed the work of Jean Servais Somian, who divides his time between Ivory Coast and Paris, and French artist Ana Zulma. The exhibition, ‘Babitopie (Entre-Deux)’, showed Somian’s furniture carved from the trunks of coconut palms alongside photographs of local people in Abidjan taken by Somian, painted over by Zulma. Among Somian’s pieces are stools and consoles embellished with wooden beads, and mirror-encrusted totems with holes carved into them where books and magazines can be inserted.

Work by Jean Servais Somian, 2019

COURTESY: Galerie Cécile Fakhoury / PHOTOGRAPH: Guillaume Bassinet

“He plays with the codes of the material and distorts objects in atypical ways to create new, unique forms, engendering an ambivalence between aesthetics and usage,” says Fakhoury, who discovered Somian’s work a decade ago.

Somian, 48, studied cabinet-making with Georges Ghandour in the Ivorian city of Grand-Bassam and worked in Paris and Switzerland before exhibiting at the 2002 International Design Biennale of St-Etienne. Following this, he established production in Ivory Coast in collaboration with local craftsmen. “When I discovered the coconut palm, whose wood is usually used to warm a hearth, I found it strange and beautiful to work with,” he says. “I wanted to impose my signature so it could become an object at the crossroads of sculpture and design. It’s the most magnificent plant: we can thatch roofs with its leaves, eat and make cosmetic products with its fruit, and make furniture from its trunk.”

Jean Servais Somian, ‘Nouveau Monde’, 2019

COURTESY: Galerie Cécile Fakhoury / PHOTOGRAPH: Guillaume Bassinet

Somian buys coconut palms from landowners planning to cut them down. “When the landowners decide to build a house, they call and ask me if I want to buy the trunks and I choose the ones that interest me. Now they know that I want to buy them, they no longer throw them away,” says Somian, whose ‘Wooden Coconut Mobile Bar’ – an oblong bar on wheels loosely inspired by a doctor’s briefcase – won the best object award at Beirut Design Fair last September.

In his Grand-Bassam atelier, the bark is removed, the wood is carved and sculpted, and forms take shape. Afterwards, the pieces are transported to his atelier in Abidjan to be turned into works of design: drawers are added to cabinets, legs to consoles, and finishings – such as bits of ox bone – are applied to the wood.

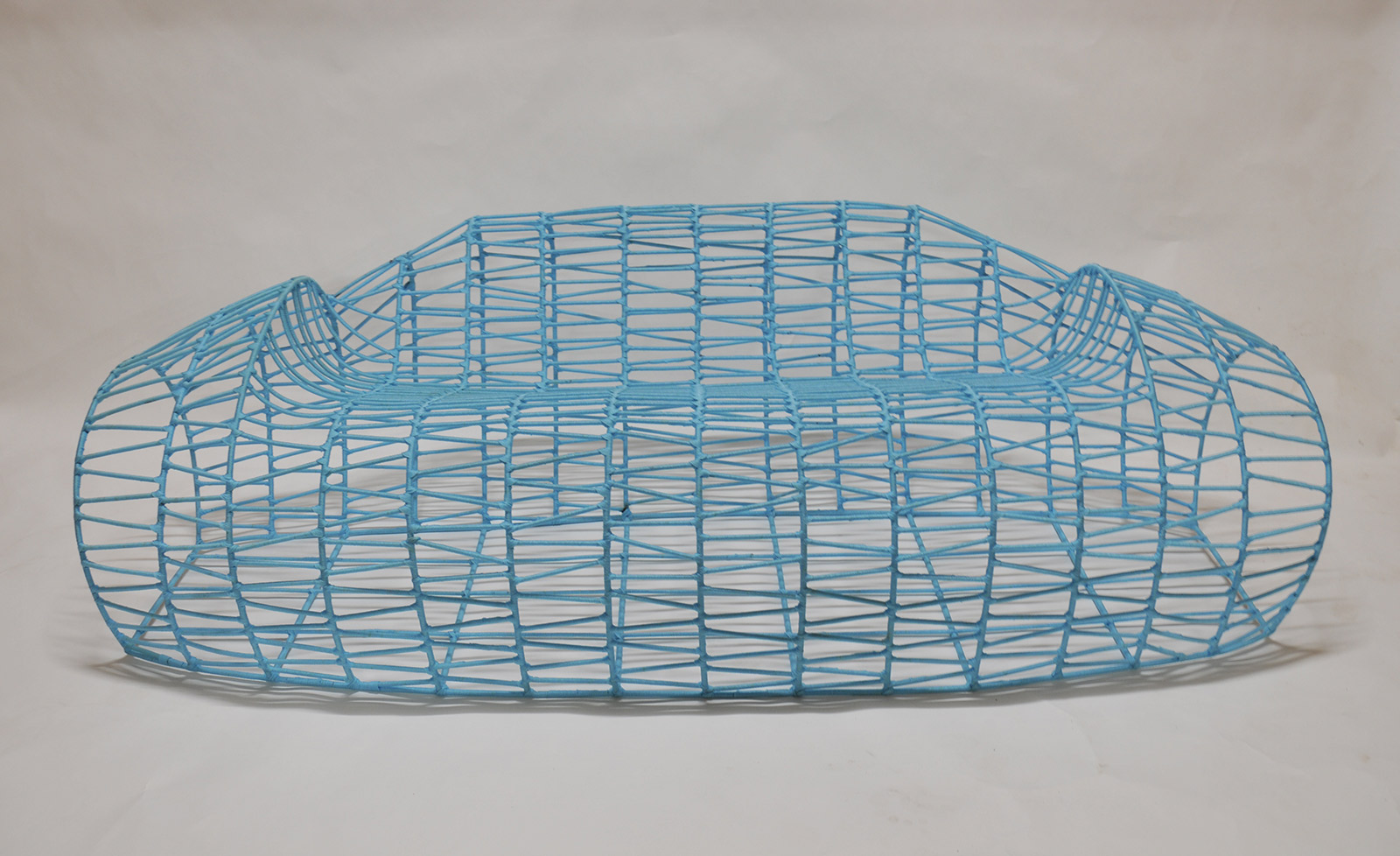

Somian also reconfigures the discarded canoes of Ivorian fishermen into sofas by adding fabric onto the empty inner structure and legs onto the base. “It saddens me when old and tired fishermen leave their canoes at the water’s edge and they become rotten,” he explains. “As a designer, I want to find a solution and bring something magical to them.”

Jean Servais Somian, ‘Banquette Pirogue’, 2014

COURTESY: Jean Servais Somian

Somian, who feels affinity with Senegal’s Bibi Seck and Burkina Faso’s Hamed Ouattara, believes that African designers are driven by a shared philosophy: “By using locally sourced or recycled materials, we’re transmitting a message: that one needs to look at what’s happening close-by and facilitate the livelihood of the local community. In Africa, we don’t have big manufacturing machines but that doesn’t mean we can’t create with what we have.”

Hamed Ouattara, ‘Indigola’, 2018

COURTESY: Out of Africa Gallery, Barcelona

Although styles vary – partly due to different tribal influences – reinterpreting traditional craftsmanship and recycling materials are commonalities of design made in Africa. For instance, the Senegalese designers Baay Xaaly Sene (BXS) and Ousmane Mbaye have both ingeniously created furniture from old petrol barrels. A parallel trend is how interest in African design has filtered into the mainstream – as exemplified by IKEA launching its Överallt collection last year, made by ten African designers including Issa Diabaté, Selly Raby Kane and Bethan Rayner and Naeem Biviji.

Ousmane Mbaye, ‘Tabouret Patrimoine’, 2006

COURTESY: Ousmane Mbaye

Taking a slightly different tack, Jomo Tariku, an Ethiopian-American industrial designer, gleans ideas from the African continent in a quest to define a new language of contemporary furniture. One such example is his ‘Birth Chair II’ (2016). Made from blackened wood with white motifs painted on the backrest, it resulted from deconstructing traditional African birthing chairs that are used in parts of Sub-Saharan Africa to provide support to pregnant women during childbirth.

Jomo Tariku, ‘Birth Chair II’, 2016

COURTESY: Jomo Tariku

An early pioneer of African contemporary design is Mali’s Cheick Diallo, whose furniture was included in the seminal ‘Africa Remix’ exhibition at the Hayward Gallery and the Centre Pompidou, among other venues, in 2004. His work is in the collection of the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris and was exhibited by Bamako Art Gallery at the fair AKAA (Also Known As Africa) in Paris in November.

After studying architecture and design in France, Diallo lived in Rouen, travelling regularly to Bamako to collaborate with local craftspeople. He returned to Bamako six years ago. “I wanted to show that it’s possible to make design in Mali,” Diallo, 59, told me during an exhibition of his work in his house and garden (designed by his architect father) in 2017. “My philosophy was to develop manual, artisanal savoir-faire, because industry doesn’t exist over here, and make contemporary, luxury objects with our own hands without importing things from abroad. People didn’t believe me when I said my objects were made here.”

Cheick Diallo, ‘Woo’ armchair, 201o

COURTESY: Cheick Diallo

Diallo works with weavers to create meticulously woven and braided furniture and lighting, some pieces revealing a western sensibility informed by Frank Gehry, Ron Arad and Constance Guisset. Other pieces are made with recycled metal on a large metalworking site. “Africa needs to show that it can propose design projects to the whole world – that’s the ambition and now it’s happening on a bigger scale,” says Diallo, who was commissioned to make furniture for the French and Belgian embassies in Bamako. Regarded as the “grandfather of African design”, he was a co-founder and president of the Association of African Designers and organises workshops for young designers in Ivory Coast, Senegal, Ghana, Morocco and Tunisia.

“Cheick Diallo introduced the idea of reinventing local savoir-faire in Africa in the 1990s with an intellectual, conceptual and rigorous approach,” says Pascale Revert, founder of 50 Golborne in London. Revert discovered Diallo’s work 15 years ago through her first gallery, Perimeter Art & Design in Paris, and is one of several collectible African design dealers, along with Southern Guild in Cape Town. At Collect, the International Art Fair for Modern Craft and Design in London, she presented Uganda’s Sanaa Gateja who makes mural beadworks, Nigerian ceramicist Ranti Bam and Senegalese furniture designer Balla Niang.

Cheick Diallo, ‘Samsara’ lounge chair, 2011

COURTESY: Cheick Diallo

Although the market for contemporary design from Africa is led by European and American clients, both Fakhoury and Revert believe the number of local collectors is growing. “Some live abroad, others have returned to their country of origin and have purchasing power,” Fakhoury says.

“The local African bourgeoisie is becoming interested in unique pieces in galleries in Abidjan, Lagos, Johannesburg, Cape Town and internationally,” Revert concedes. “But economic structures are needed for significant market development. One hopes that ‘starchitects’ of African origin, such as David Adjaye and Francis Kéré, who are increasingly involved on the continent, will call on African designers for hotel, residential and social projects, like schools.”

Equally, venues like the Palais de Lomé are needed to stimulate a passion for design locally through staging exhibitions like the one on Aguessy.

Installation view, Kossi Aguessy’s exhibition at the Palais de Lomé

PHOTOGRAPH: Nicolas Robert

‘Infinity: Kossi Aguessy (1977-2017)’ is at the Palais de Lomé until March 2020.

Galerie Cécile Fakhoury – aims to promoted contemporary art in Africa.

Collect – the only gallery-presented art fair dedicated to modern craft and design.

50 Golborne – contemporary African Art and Design Gallery London.

Jomo Tariku – Ethiopian American artist and industrial designer.