Art with Design

In displaying art with design in spaces configured to suggest domestic interiors rather than white cubes, galleries are blurring the distinction between the two.

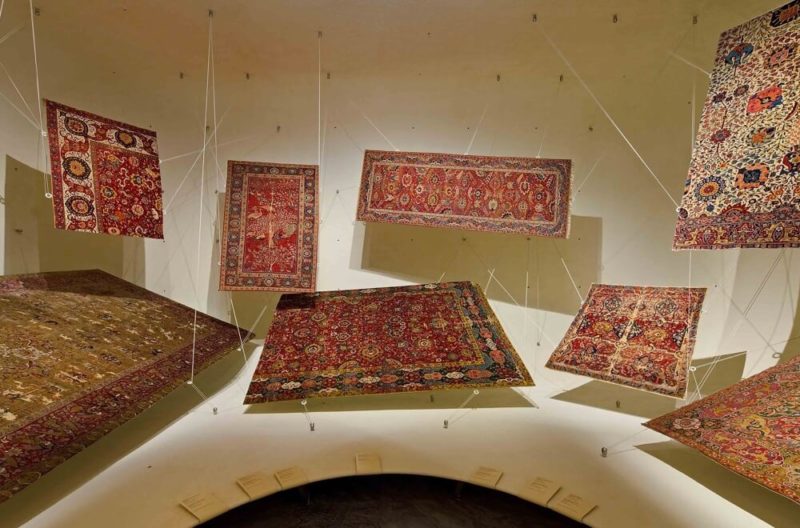

Installation view, Hauser & Wirth at Frieze Masters, 2018

COURTESY: Hauser & Wirth

WHEN, A DECADE ago, the Scandinavian artist partnership Elmgreen & Dragset turned the Danish and Nordic Pavilions at the Venice Biennale into the fully furnished art-filled homes of two imaginary collectors, they apparently sparked a trend among dealers. Art and design were seen to complement each other within the confines of an ostensibly domestic space, within which there was a narrative at play.

Witness Gagosian’s booth at this year’s FIAC in Paris – a mise-en-scène inspired by a villa at Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat, complete with mantelpiece cluttered with objects and framed photos, logs in the grate, and a suite of early 20th century rattan and bamboo furniture at the centre – and it’s clear commercial galleries are thinking along similar lines. Staying at the Villa Santo Sospir between 1950 and 1963, Jean Cocteau had “tattooed” – his verb – its interior walls with tempera illustrations of deities from Greek mythology. These too had been recreated on the Sheetrock walls of the booth, against which were displayed works by Alexander Calder, Alberto Giacometti, Yves Klein, Fernand Léger, Man Ray, Henri Matisse and Francis Picabia, all artists who frequented the South of France.

Installation view, Gagosian at FIAC, 2019

COURTESY: Gagosian © 2019 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York ; © Succession Picasso 2019 ; © Adagp / Comité Cocteau, Paris, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris 2019 / PHOTOGRAPH: Zarko Vijatovic

Over on Victoria Miro’s stand, a little anteroom was dedicated to the Cuban-American artist and furniture designer Jorge Pardo. A painting hung on one wall. One of his untitled pendant lights in laser-cut translucent recycled PETG cast multiple shadows on the rest. Whether his lights are intended to illuminate, or be looked at, is a moot point. Pardo may also design every sort of furnishing from marquetry coffee tables, cane bedheads and rocking chairs to floor tiles (not least for the collector Maja Hoffmann’s hotel L’Arlatan, 750 km south in Arles), but the fact that he specifies the type of bulb implies they are works of art.

Jorge Pardo, ‘Untitled’, 2017

COURTESY: Jorge Pardo and Victoria Miro, London/Venice © Jorge Pardo

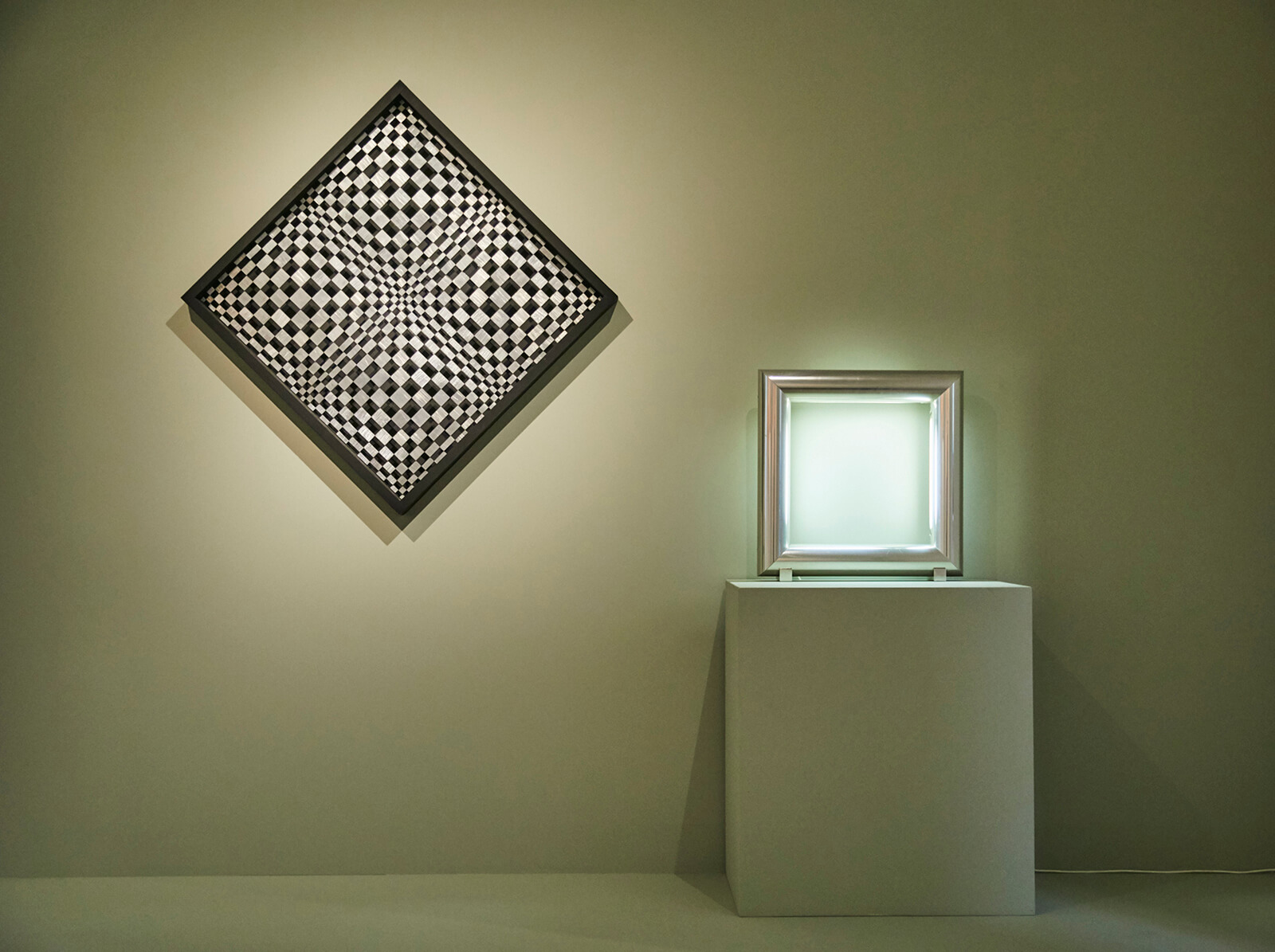

It’s a question that arises again at the exhibition of post-war Italian art and design currently on at Tornabuoni’s French outpost over in the Marais. Look at the opening juxtaposition of Dadamaino’s ‘Oggetto Ottico Dinamico’ (1962-71) with Nanda Vigo’s ’Utopia’ (1970), and it isn’t immediately obvious which is the art and which the design.

Dadamaino, ‘Oggetto Ottico Dinamico’, 1962-71 and Nanda Vigo, ’Utopia’, 1970

COURTESY: Tornabuoni / PHOTOGRAPH: Say Who / Valentin Le Cron

The Dadamaino work is described as “milled aluminium plates on nylon threads on a wooden structure”, an Op Art arrangement of gradated squares and rectangles that fools the eye into discerning a third dimension. It could, at a pinch, be a tray, except that no sane collector would risk using something so exquisitely crafted. In any case Dadamaino was an artist, one of the few female pioneers of the avant-garde in 1960s Italy. Ergo it’s a work of art.

The piece is hung “in dialogue with” an empty frame of polished tubular steel inset with fluorescent bulbs. Through it, explains the architect Charles Zana, who curated the exhibition, one looks into a void, which “is how Vigo imagined Utopia”, hence the name she gave the work, and the one he took for the show. To him it’s a work of art. Dan Flavin had been using fluorescent tubes in his work since the early 60s, and they counted as art. But perhaps because Vigo also made tables and shelves and mirrors, ‘Utopia’ tends to be classified as a lamp, and its creator a designer.

But questions of taxonomy are not what interests Zana. To him, artists, architects and designers are all engaged, as he puts it, in “the same spiritual research, the same quest for the absolute”. So the exhibition is intended to prompt, he says, “a kind of conversation,” about the “commonality” discernible in works by 17 artists and 17 designers, all Italian and all broadly contemporary. By presenting us with an exhibition of such “meetings”, he’s inviting us to think about “the sharing of values,” he says.

Gaetano Pesce, ‘Sansone’ table, 1980; Alighiero Boetti, ‘Mappa del mondo’, 1980; Gio Ponti, ‘Pavone’ ceiling lamp, circa 1950

COURTESY: Tornabuoni / PHOTOGRAPH: ©Matthieu Salvaing

Some of the connections he makes seem obvious: the pairing of Gaetano Pesce’s ‘Sansone’ table cast in resin in the colours of the Italian Tricolore before Alighiero Boetti’s national-flag embroidery ‘Mappa del mondo’; or Superstudio’s fabulously kitsch (and correspondingly comfortable) fake leopardskin ‘Bazaar’ modular sofa paired with two of Piero Manzoni’s ‘Achrome’, framed squares of white synthetic fur and fibreglass wool. Elsewhere he pairs mirror with mirror (Allesandro Mendini’s ‘Scivolavo’ chair with a Michelangelo Pistoletto mirror painting) and wood with wood (Enzo Mari’s rustic construct-it-yourself ‘Autoprogettazione “P”’ chair and a Mario Ceroli assemblage of timber offcuts.)

Superstudio, ‘Bazaar sofa’, 1968; Piero Manzoni, ‘Achrome’, 1961-2

COURTESY: Tornabuoni / PHOTOGRAPH: ©Matthieu Salvaing

But there are also combinations to prompt you to look afresh. Alessandro Mendini’s ‘Poltrona di Proust’ armchair, designed in 1978 but not realised until 1987, has been positioned before Piero Dorazio’s painting ‘Penumbra III°’ (1976), a “chromatic fantasy”, in Zana’s words, that initially appears to harmonise with the chair’s upholstery. “The chair is of a type you see in all country houses, in all our grandmothers’ homes,” says Zana of the 19th-century fauteuil. But in painting the canvas with which it has been upholstered as well as its ornate carved frame in colourful pointillism, he made it, says Zana, “a manifesto for the Alchimia movement”, whose mission was to move design on from Modernism and to make unique pieces that functioned, rather than furniture for a wider market. In other words, this is not just a chair, it’s a painting. Though Mendini’s splashy brushwork could not be further from Dorazio’s precise handling, each carefully rendered lozenge of colour delineated in a darker shade.

Alessandro Mendini, ‘Poltrona di Proust’ armchair and Piero Dorazio, ‘Penumbra III°’, 1976

COURTESY: Tornabuoni / PHOTOGRAPH: Say Who / Valentin Le Cron

The reference to Proust alludes not just to the idea that memories can be triggered by everyday objects, but that in redecorating or recasting something familiar and ordinary one can begin to see it, to paraphrase Proust, “with other eyes”. “If you saw a chair like this in a home,” says Zana, “you might not like it, or give it a second thought”. Here, though, it’s become something to appraise and think about.

The idea for the show was prompted by an exhibition of paintings by Giorgio di Chirico, at which Zana, who made his curatorial debut two years ago when he put together a show of works by Carlo Scarpa and Ettore Sottsass at the Olivetti Foundation in Venice during that year’s Biennale, “saw an obvious, though invisible dialogue with Sottsass’s work. The painter and the architect [were] conducting the same spiritual research,” he says. “A quest for the absolute.”

(From left to right) Ettore Sottsass, ‘Grande vaso afrodisiaco per conservare pillole antifecondative’, 1964; di Chirico, ‘La grande tour’, 1915; di Chirico, ‘L’addio dell’amico che partr all’amica che rimane’, circa 1950; Ettore Sottsass, ‘Barbarella’ cabinet, 1966

COURTESY: Tornabuoni / PHOTOGRAPH: Say Who / Valentin Le Cron

Or take his juxtaposing of Sottsass’s polychrome ceramic ‘Grande vaso afrodisiaco per conservare pillole antifecondative’ (1964) and ‘Barbarella’ cabinet (1966) with di Chirico’s paintings ‘La grande tour’ (1915) and ‘L’addio dell’amico che partr all’amica che rimane’, and aesthetically the connections are clear. As, indeed, are those between Lucio Fontana’s ‘Concetto Spaziale, Attese’ (1964) and Carlo Mollino’s 1959 chair for the architecture faculty at the Polytechnic of Turin, the slit between its stiles echoing the punctures in Fontana’s canvas.

Lucio Fontana, ‘Concetto Spaziale, Attese’, 1964; Carlo Mollino, ‘Chair’, 1959

COURTESY: Tornabuoni / PHOTOGRAPH: Say Who / Valentin Le Cron

“Look how the use of gilt gives each a Byzantine quality,” urges Zana, when we come upon Enrico Castellani’s metallic ‘Superficie’ (1961) and Carlo Scarpa’s ‘Crescita’ (1968). He urges me to consider, too, the astral references in Gio Ponti’s ‘Pavane’ chandelier (circa 1950) and its bearing on Arnoldo Pomodoro’s 1999 sculpture ‘Disco’. More than that they are displayed as a collector might opt to display them at home, where aesthetic connections may assume precedence over intellectual ones, though not necessarily at the expense of them.

Enrico Castellani, ‘Superficie’, 1961; Carlo Scarpa, ‘Crescita’, 1968

COURTESY: Tornabuoni / PHOTOGRAPH: Say Who / Valentin Le Cron

Hauser & Wirth, whose highly conceptual booths and collaborations with Moretti Fine Art, have become a feature of Frieze Masters in London, also opted to display 20th century Italian furniture alongside both modern and renaissance works of art last month. This year the starting point for their exhibition was the milieu of another Italian avant-garde artist and intellectual Fabio Mauri, and so the exhibition included works by more than half the artists and designers on show at Tornabuoni – Alberto Burri, Boetti, Castellani, Dadamaino, Dorazio, Tano Festa, Fontana and Manzoni – only this time in dialogue with Italian old masters.

Installation view, Hauser & Wirth and baukuh at Frieze Masters, 2019

COURTESY: Hauser & Wirth

At the start of Ben Eastham’s foreword to the accompanying book, Before or After, at the Same Time: Rome, Milan, and Fabio Mauri, 1948 – 1968, he alludes to a sofa that had belonged to Mauri’s grandfather on which four generations of artists and other celebrities had sat. Mauri inscribed the names of all those he could remember on a lead plate, which, propped up on the sofa, became part of his 1999 installation ‘Quadreria’. It made sense then that prominent in the booth – which evoked a suite of six dark wood-panelled rooms expensively furnished in a mid-century Modern style (designed by the Milan- and Genoa-based architects baukuh) – was a sofa. In this instance, Gianfranco Frattini’s ‘872’, (circa 1958), upholstered in pink velvet, one of a number of furnishings loaned by the Rome-based gallery Giustini/Stagetti, which specialises in pieces by Franco Albini, Ponti and Sarfatti.

Installation view, Hauser & Wirth and baukuh at Frieze Masters, 2019

COURTESY: Hauser & Wirth

In front of the sofa hung another Fontana ‘Concetto spaziale, Attese’; behind it two of Mauri’s own tempera paintings (both entitled ‘Smoking’, 1969) and adjacent to Enrico Baj’s collage ‘Trillalì-Trillalà’. A 19th century Neapolitan School carving of a skull wearing a crown in marble stood on the marble coffee table before it. “It really had the feel of 1950s Milan,” says Neil Wenman, senior director at Hauser & Wirth, who oversaw the project. “You need the details to ring true.”

The ideas for such booths, he explains, come from an “awareness that collectors collect across genres” and that, quite apart from being a “fun and interesting way” to engage with artists and their estates, creating a narrative to connect them helps “people to engage with the work”.

Installation view, Hauser & Wirth at Frieze Masters, 2017

COURTESY: Hauser & Wirth

In 2017, for example, the architect Luis Laplace conceived what he called “a fictional collector’s living room inspired by the Parisian homes of Yves Saint Laurent and Jacques Doucet” for Hauser & Wirth’s stand at Frieze Masters, “an abstraction of a domestic interior [in which the] furniture provides a context […] where tables stand in for plinths and the works are exhibited according to the collector’s individual taste, not categorised by date or style.”

Installation view, Hauser & Wirth at Frieze Masters, 2017

COURTESY: Hauser & Wirth

The following year their presentation, also designed by Laplace, focused on Stephen Spender’s artistic circle and his relationship with Arshile Gorky’s family.But if the real challenge, says Wenman, is to “create a space that gets the narrative across”, the presence of furniture also allows collectors “to sit down and relax and maybe engage a bit more with the work, to have a quality experience. That’s really what we are hoping to achieve.”

Installation view, Hauser & Wirth at Frieze Masters, 2017

COURTESY: Hauser & Wirth

It’s a trend that’s prompting artists to think too. “Perhaps unusually for a contemporary artist, I often prioritise how my work might flourish in a domestic setting,” said Grayson Perry ahead of the opening of his current exhibition of ceramics and rugs at Victoria Miro in London’s Mayfair. “I always imagine how it’ll sit within the decorative scheme of a collector’s house.” Indeed his pots, he says, look “more at home in a sitting room than an art gallery.”

Grayson Perry, ‘Thin Woman with Painting’, 2019

COURTESY: Grayson Perry and Victoria Miro, London/Venice © Grayson Perry

Grayson Perry, ‘Thin Woman with Painting’, 2019 (detail)

COURTESY: Grayson Perry and Victoria Miro, London/Venice © Grayson Perry

This year, “channelling” what he calls his “transgressive spirit”, he has for the first time turned one of his pots into a table lamp – an act he describes as “one of the great sacrileges against art committed by interior designers”. Entitled ‘Money on Holiday’, it incorporates photographs by Martin Parr (never afraid to snap at the hands that feed him, Perry “particularly” likes, he told the Financial Times, the “close-ups of gnarled manicured hands, freighted with huge jewels and clutching flutes of champagne”) and an unfashionable lampshade of stretched pale blue silk dupion. He hasn’t, though, specified the type of bulb. So is it art?

“Utility,” as he also told the Financial Times, “is often cited as the boundary that divides art from design.”

Grayson Perry, ‘Money on Holiday’, 2019

The question of what raises lighting “to the level” of art also arises in Flavia Frigeri’s foreword to the catalogue to Tornabuoni’s ‘Utopia’ show, in which she observes “an uncanny similarity” between Gino Sarfatti’s pendant light ‘2072 Jo-Jo’ (1953) and Alexander Calder’s “famous mobiles. [Though] unlike the latter, Sarfatti’s lamp fulfils a practical use, to illuminate the modern [her italics] home.” Charles Zana has hung it above Paolo Scheggi’s three-dimensional acrylic-on-canvas painting ‘Intersuperficie curva bianca’ (1966), on which it casts a subtle glow. “But it has no function really,” he insists. It brightens a room, I counter. Sarfatti designed more than 700 lights, many of them still in production. Surely his lights were designed with a purpose in mind. “It’s more a mobile, I think,” says Zana. A work of art, then? “Yes: the light is just a pretext.” The distinction between design and art remains obscure.

(Foreground) Paolo Scheggi, ‘Intersuperficie curva bianca’, 1966; Gino Sarfatti, ‘2072 “Jo-jo”’ lamp, 1953. (Background) Andrea Branzi, ‘Bench’ from the Animali Domestici collection, 1985; Pier Paolo Calzolari, ‘Senza titolo (Sale e trifoglio)’, 1969

COURTESY: Tornabuoni / PHOTOGRAPH: ©Matthieu Salvaing

‘Utopia’ at Tornabuoni, Paris, until 21st December.

‘Super Rich Interior Design’ at Victoria Miro, London W1, until 20th December.