Lighting in Design

Designers have always experimented with light, both natural and artificial. Technology is now bringing new toolboxes and processes for contemporary creatives to play with – from LEDs to drones.

THE IMMATERIAL ESSENCE of light invariably intrigues creative minds. While Joesph William Mallord Turner captured its transcendental quality in nineteenth-century paintings, contemporary designers realise works that utilise its enigmatic energy as a vital component of their artistic language.

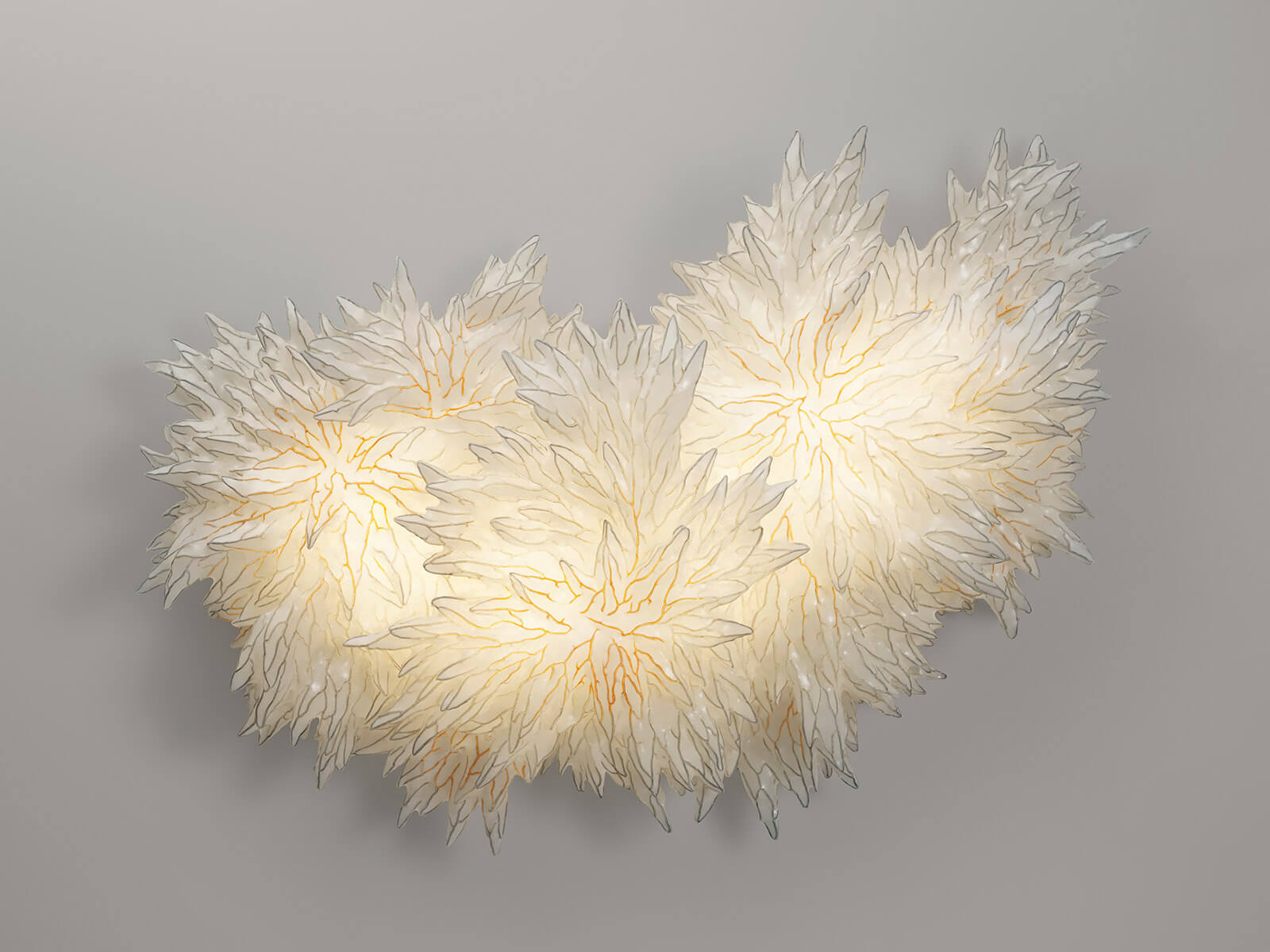

Ayala Serfaty, ‘Clear II’, 2018

COURTESY: Galerie BSL

A recent performance art installation, ‘Franchise Freedom’, for instance, was created by Dutch design studio Studio Drift in Rotterdam on 5th May 2020. A swarm of 300 drones illuminated the sky, flying in programmed formation above the River Nieuwe Maas and Erasmus Bridge. Produced with the art organisation Mothership, it culminated in the transformation of the drones into a pulsating red, white and blue heart, representing the colours of the Netherlands’ flag. The piece paid tribute to Liberation Day, marking the end of Nazi Germany’s occupation in 1945, and to the heroic efforts of health workers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Studio Drift, ‘Franchise Freedom’, Rotterdam, 2020

COURTESY: Studio Drift / PHOTOGRAPH: ©Ossip van Duivenbode

‘Franchise Freedom’, the first iteration of which was presented during Art Basel Miami Beach in 2017, evolved from the interactive, sculptural installation ‘Flylight’ (2015), inspired by the idea of a flock of birds. The latter is composed of dozens of suspended, delicate glass tubes that become brighter or duller in order to mimic the behaviour of starlings in flight, thus using technology to evoke a natural phenomenon.

Studio Drift, ‘Flylight’, 2015

COURTESY: Carpenters Workshop Gallery

Fascination with applying technology has consistently driven the creation of lighting. The invention of the electric lightbulb in the late 19th century ushered in the development of lighting as a luxury good. In the early 1900s at Tiffany Studios, Louis Comfort Tiffany created leaded glass lamps with brightly coloured, intricately crafted floral patterns for affluent households.

Tiffany Studios, ‘Pond Lily’ table, circa 1903

COURTESY: Christie’s

The Art Nouveau movement of the 1920s/1930s saw French interior designers like Armand Albert Rateau and Pierre Chareau, along with the artist Alberto Giacometti, making unique or limited-edition lamps that are highly sought-after today. A ‘Pond Lily’ table, circa 1903, by Tiffany Studios went under the hammer for $3.4m at Christie’s in 2018, while a floor lamp by Chareau fetched $2.2m.

Pierre Chareau, ‘Religieuse’ floor lamp, model SN13, circa 1923

COURTESY: Christie’s

“In the first half of the 20th century, designers used lighting to create cultural, iconic pieces that can command exceptional prices,” Agathe de Bazin, Christie’s head of design sales in Paris, says. “Throughout the century, designers were interested in technical innovations, like neon, and reinterpreted them.”

In the 1930s in Italy, Arteluce (founded by Gino Sarfatti), FontanaArte (co-founded by Gio Ponti and Pietro Chiesa) and Arredoluce (founded by Angelo Lelii) began manufacturing sharp, modern designs. In the 1950s in France, Serge Mouille and Pierre Guariche also made modern classics while Mathieu Mategot registered a patent, Rigitulle, for his invention of pleated, perforated metal and integrated shelves, small tables and plant pots into several lighting pieces. The lighting designs of French designer Jean Royère and, later, Claude Lalanne – known for whimsical evocations of flora and fauna, – have both proved immensely popular, commanding high prices at auction, as have those of Scandinavian designers such as Alvar Aalto, Paavo Tynell and Poul Henningsen.

Mathieu Mategot, ‘Suspension’ suspension light, circa 1954

COURTESY: Galerie Matthieu Richard, Paris / PHOTOGRAPH: © Sylvie Chan-Liat

The Light and Space artists in the US, such as James Turrell, known for his installations bathed in coloured light, have been inspirational for some contemporary designers. Yet in terms of industrial design and the illumination of buildings, it is Ingo Maurer, the late German designer who is frequently referred to as the “poet of light”. The American designer Johanna Grawunder cites Maurer’s “poetic, user-friendly refining” of technology as something that has guided her. “When a new technology comes out, I find myself thinking, ‘What would Ingo do?’” she says.

A passionate advocate of integrating coloured lighting into design and architecture, Grawunder designed the lighting for Van Cleef & Arpels’ recent exhibition at the ornate Palazzo Reale in Milan. By adding lighting to the display vitrines and their immediate surroundings, Grawunder created a theatrical backdrop to the jewellery that enhanced the thematic atmosphere of each particular room, without overpowering the tapestries and wallpaper. “We used very specific colour-changing light effects that we could programme to get the exact pink we wanted in a certain room to correspond to either a piece of jewellery or something in the room,” San Francisco-based Grawunder explains.

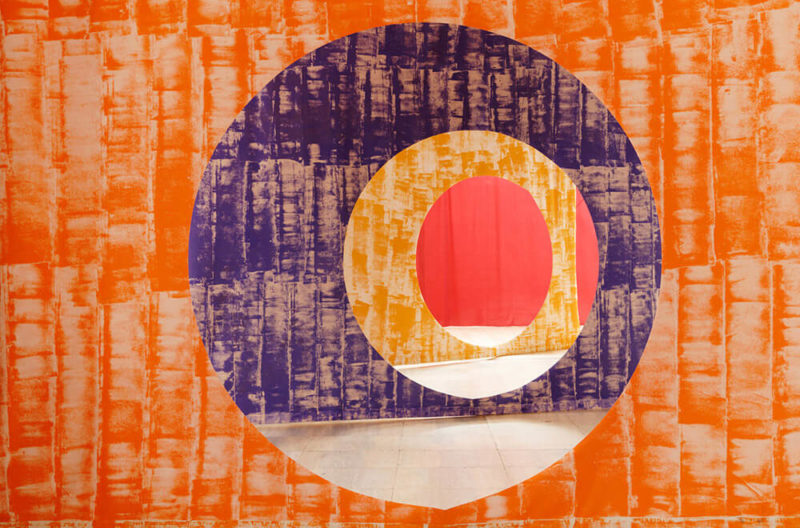

Johanna Grawunder, ‘Four Squares’, 2018

COURTESY: Carpenters Workshop Gallery

Grawunder began exploring the qualities of coloured lighting whilst working for Ettore Sottsass from 1985-2001 before opening her eponymous studio. “When I was working with Sottsass, there was very little integrated light in architecture and little attention to what would happen to the space at night with man-made light,” Grawunder says. “I found that I was looking through the Pantone book for colours I couldn’t find, that there was an entire section missing on the vibrancy of colour that you see in real life. I started working with coloured light to get these saturated, sophisticated colours that you could put on any surface.”

Grawunder’s projects range from limited-edition pieces to large-scale interventions, such as installing coloured lighting in San Francisco Airport’s glass elevators. “Using coloured lighting is a fast-track way to get people to feel emotion,” Grawunder states. In the future, she hopes that coloured lighting might be used for path-guiding in airports and to generate soothing experiences rather than a “wow moment”. As she says, “It takes a lot of discipline to use technology to get a beautiful, artificial light that’s not aggressive and gives people a pleasant experience.”

The Danish designer Astrid Krogh has used coloured light to enhance wellbeing in meditative works. In 2015, she installed a vertical sequence of five round “slices of light”, with a sky on each side, in a dark atrium of Nya Karolinska Hospital in Stockholm. Titled ‘Skylight’, the gradations of colour change throughout the day to imitate daylight, from sunrise to sunset. “When you are going through a difficult time in your life, you want to be reminded of something essential, like light,” Krogh says. “People can sit around the different levels of the atrium and the work can be comforting to them.”

Astrid Krogh, ‘Skylight’, 2015, Nya Karolinska Hospital, Stockholm

COURTESY: Astrid Krogh

Krogh often seeks to convey the physical impact of the view from her countryside atelier of the sea, the horizon and the light. She is currently working on an installation for a children’s hospital in Sweden that is inspired by the sensation of lying on a flower-dotted meadow and gazing at the sky. “I’m trying to find a universal language with light,” Krogh says. She also creates luminous, large-scale weavings with optical fibres and paper yarn in a spectrum of shifting colours, again mimicking the changing sky.

For 21st-century designers, the opportunities for experimenting with electricity and technology to create lighting are endless, believes the British designer Paul Cocksedge. “There are so many types of technology that allow people like myself to experiment and discover those magical moments that you’ve never seen before,” he says.

In 2011, Cocksedge was commissioned by the City of Lyon to create a public installation ‘Bourrasque’, which was presented in the courtyard of the City Hall during its Festival of Light. A long trail of what resembled curved sheets of glowing paper drifted up into the nocturnal sky – the onlookers gathered below looked up in wonderment. “It’s the emotional effect it had on people which was the most powerful thing,” Cocksedge remarks. The piece translated the concept of an earlier installation, ‘A Gust of Wind’ (2010), into lighting. The previous piece, shown at the Victoria and Albert Museum, comprised of curved sheets of Corian suspended in the air, looking like a stack of paper that had been blown into the air.

Paul Cocksedge, ‘Bourrasque’, 2011

COURTESY: © Mark Cocksedge

Lighting, of course, has often formed just one part of a designer’s multi-faceted output. Think of Mathieu Lehanneur’s ‘Twisted Infinity’ (2018), recalling a golden bow on a ribbon, and ‘Les Cordes’ (2018), whose array of glass cylinders emerge from the ceiling in a revisitation of the chandelier, as examples. Or the Bouroullec brothers’ ‘Lianes’ (2010), a looped, leather-clad pendant lamp, and Noé Duchaufour-Lawrance’s ‘Naturoscopie’ (2012), which features Plexiglas branches displaying kinetic images of nature.

Olga Engel, ‘Yeti’, 2019

COURTESY: Galerie Armel Soyer

“Olga Engel sculpts poetic lamps from innumerable, teardrop-sized porcelain pieces”

Vincenzo De Cotiis, ‘DC1911’ table lamp, 2019, from the ‘Éternel’ series

COURTESY: Carpenters Workshop Gallery

“Vincenzo De Cotiis has collaborated with Murano’s glass blowers to make striking, graphic lamps with silver leaves and brass”

Often inherent to lighting is a link with sculpture and craftsmanship. In his studio over the past decade, Nacho Carbonell has developed organic and cocooned, metal mesh shapes in works that, grouped together, can loosely evoke a forest of lights or vegetation. Last year, the Spanish designer welded green glass from beer bottles with metal, paper paste and wires to make forms inspired by the Bonsai tree with light shimmering through. “The colours of the reflections and shadows, and how the light goes through the glass to create optical illusions, bring a special mood into the interior, like stained glass windows in a church,” Carbonell says. “With most of my work, what I’m trying to create is an atmosphere more than an object.”

Nacho Carbonell, ‘Broken Mixed Glass Bonzai’, 2019

COURTESY: Carpenters Workshop Gallery

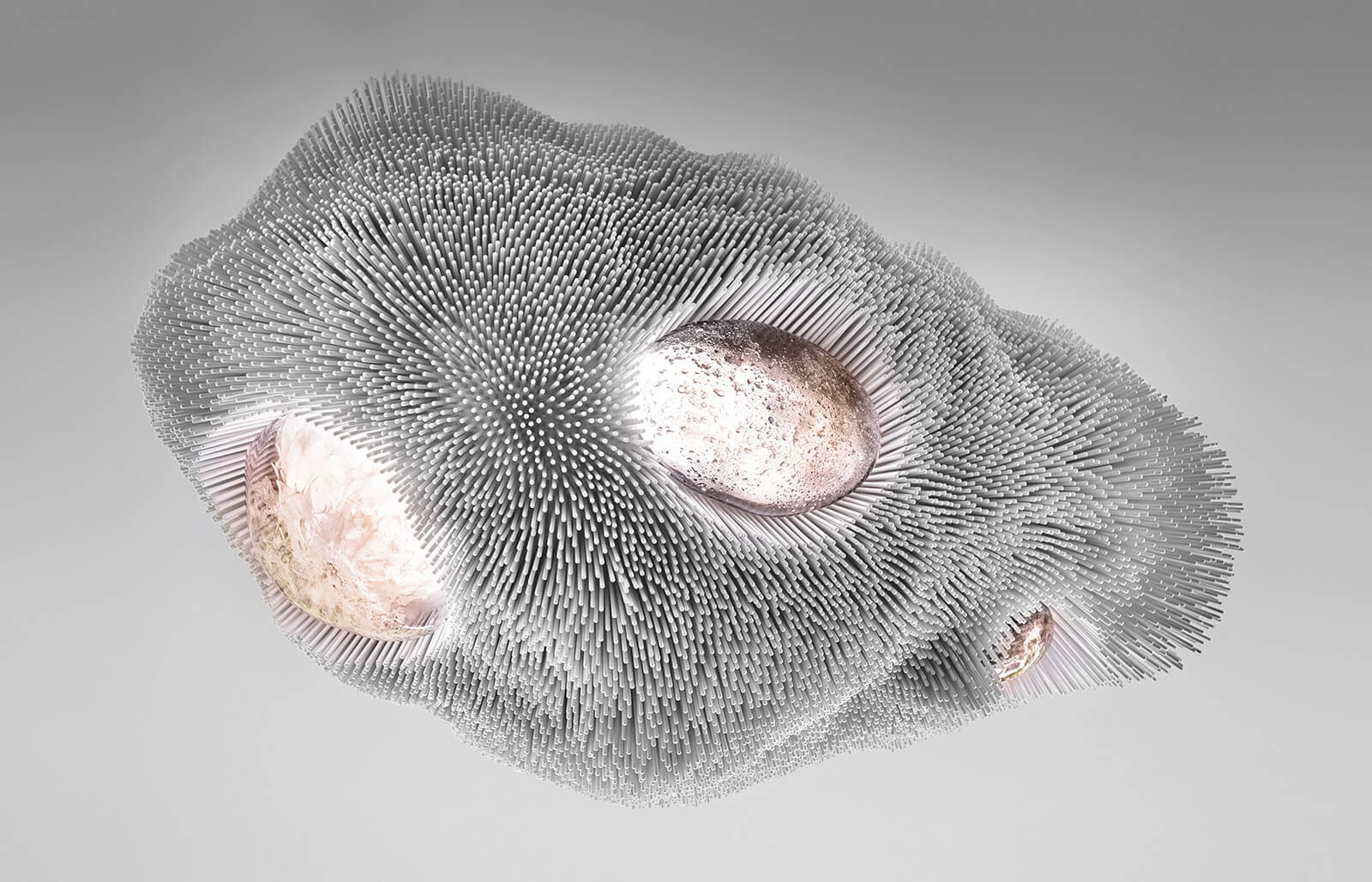

Originality of language is evidenced, too, in how Pia Maria Raeder meticulously cuts and arranges hundreds of lacquered beech rods with blown glass and LEDs to make her ‘Sea Anemone’ (2019) ceiling light sculptures. Ayala Serfaty realises wall light sculptures from glass and polymer – such as ‘Clear II’ (2018) that brings to mind white flowers in blossom – and Olga Engel sculpts poetic lamps from innumerable, teardrop-sized porcelain pieces. Vincenzo De Cotiis, meanwhile, has collaborated with Murano’s glass blowers to make striking, graphic lamps with silver leaves and brass.

Pia Maria Raeder, ‘Sea Anemone’, 2019

COURTESY: Galerie BSL

By contrast, John Procario makes undulating shapes from micro-laminated bent wood fused with white LEDs. “I like thinking of light as an interesting sculptural element – because light is a volume itself – and controlling it,” says the American designer, who is influenced by Brancusi and Donald Judd. Looking ahead, Procario plans to make a large outdoor lighting sculpture for a garden that can “interact with the scale of nature”.

John Procario, ‘Monumental Freeform Series’ (by Commission)

COURTESY: Todd Merrill Studio

As designers stretch their imaginations in tandem with pushing the boundaries of materials and technology, the scope for interpreting lighting in a rich body of artworks continues to grow.