Murano in crisis

Soaring gas prices, competition from cheap glass imports and ageing maestros – can glassmaking survive in Venice?

Glassworks by Lino Tagliapietra

COURTESY: Lino Tagliapietra

THE UKRAINE WAR has dramatically increased the price of gas in Europe. Among many consequences, has been a direct impact on glass art and design centres across the region – from Stourbridge to Nový Bor. In the Czech Republic, for instance, the market price of gas for 2023 is currently twelve times the 2021 price. The Czech government has recently promised to support small industries by imposing a cap; however, some factories have already closed, at least temporarily.

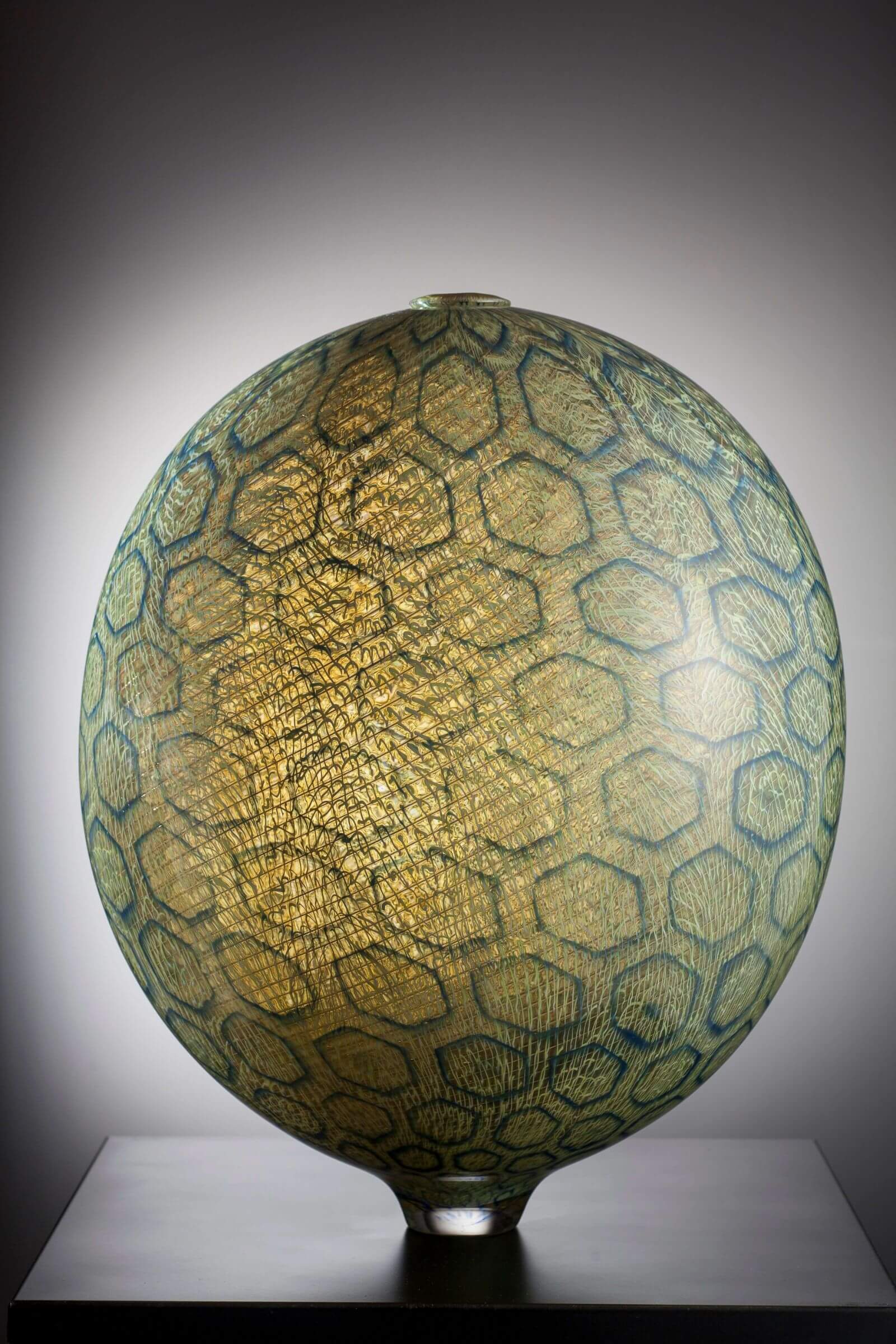

Lino Tagliapietra, ‘Secret Garden’

COURTESY: Lino Tagliapietra

One of the glass centres worst affected by the gas shortage is Murano, in Venice. With furnaces that are almost entirely gas-powered, its network of factories, design studios and galleries has been precipitated into a crisis. Between October 2021 and July 2022, the industry received 8 million Euros in government grants. However, since the grants have ended, at least 80 percent of Murano’s factories have halted production. Gas prices are skyrocketing, says Luciano Gambaro, president of the Consorzio Promovetro Murano, which represents the industry. “In the last two months I paid as much for gas as I paid in the whole of the previous year,” he emphasises, “These figures are absolutely unmanageable.”

Not only that, but with the ongoing situation so uncertain, his firm cannot give clients a guaranteed price on commissions. He has kept just one of his three furnaces running to complete an order. After that, if prices do not fall, he too will have to close until things improve.

Lino Tagliapietra, ‘Africa’

COURTESY: Lino Tagliapietra

Many of the smaller businesses, with rent to pay and lower turnover, have already ceased operations. One of these is Vetraie Ribelli (‘rebel glassmakers’), Murano’s first women-owned glassblowing studio. Founded in January 2021 by Chiara Lee Taiarol and Mariana Oliboni, they have already established themselves as a distinctive studio, and participated in the Venice Glass Week. But in mid-September their furnaces were switched off. Instead, they were making small-scale art with borosilicate, using tanks of liquid propane as fuel for the burners. They were also planning collaborative projects both with other Muranese glassworks and with international female artists. According to Taiarol, however, such measures would not be enough in the long term, either for them or the rest of the industry. “Either gas will return as before, or the whole of Murano will have to be revolutionised.”

Lino Tagliapietra, ‘ Dinosaur’

COURTESY: Lino Tagliapietra

Gas is just the latest addition to Murano’s list of woes. A more entrenched one is the competition from cheaper production centres in other countries, especially China, which sell their goods on Murano. The existence of these ‘fakes’ continues to confuse tourists, says Gambaro, who do not understand why they should pay several times more for Muranese pieces; as a result, “they don’t buy anything at all.” The nadir came in 2015, when the local Chamber of Commerce estimated that 70 per cent of glass sold in Venice was not made on Murano.

Lino Tagliapietra, ‘Endeavor’

COURTESY: Lino Tagliapietra

There is also the perennial criticism that the industry has failed to adapt to changing times. Lino Tagliapietra is convinced that women need to be part of Murano’s future in a way that they were not of its past. Lino himself, of course, has played a vital role in opening the island up to the world. “He is an extraordinary maestro and designer, who overturned the old dogmas and so created a new way of presenting, exhibiting and even making artistic glass,” says Gambaro. The question is whether there will be any to follow him.

Lino Tagliapietra

COURTESY: Lino Tagliapietra

The 2022 Glass Week opened just as the gas crisis was starting to bite. Despite this, the mood was positive. It was striking how many entries there were from international glass artists and designers, often with a connection to Murano. “This type of exchange has become fundamental for all of us,” says Gambaro. “We have things to teach, but also things to learn.”

-

Lino Tagliapietra at work

COURTESY: Lino Tagliapietra

-

Lino Tagliapietra at work

COURTESY: Lino Tagliapietra

-

Lino Tagliapietra at work

COURTESY: Lino Tagliapietra

As if to illustrate his point, among the new stars of the programme were Tessa and Tara Sakhi, a pair of Lebanese-Polish designers and sisters from Beirut. Their exhibition in the Chiesa di San Gallo, ‘I Hear You Tremble’, was a collaboration with the maestro Fabiano Amadi and Laguna~B, a relatively young Muranese production company. The result was a series of heavy, partially distorted glass urns rolled while still hot in waste metal powder. These pieces play with the themes of ancient trade around the Mediterranean and the cross-cultural history of glassmaking.

Portrait of designers Tara and Tessa Sakhi in Murano, Venice, alongside ‘Jurat’ vessels by T SAKHI

COURTESY: T SAKHI

Collaborations between maestri and independent artists like the Sakhi sisters on unique and small-edition pieces, rather than either in-house designers or larger-scale production, look to be Murano’s best hope for the future.

If you think about it, says Lino, it is strange that glassmaking should have taken root on Murano seven centuries ago “because there wasn’t anything here – neither water, nor wood, nor sand.” “What is truly important for Murano is not a product,” says Gambaro, “glass is part of our history, culture and tradition.”

Lino Tagliapietra, ‘Dinosaur’ series

COURTESY: Lino Tagliapietra

Sometimes it seems as if that tradition itself might be part of the problem. Yet there is still no substitute for technical knowledge passed on through the generations, and a network of complementary skills – provided these are regularly injected with new life. As Lino puts it, “since history has given us this importance of being Murano, why should we let it be lost?”