Body Vessel Clay / Black Women, Ceramics & Contemporary Art

“Ladi Kwali opened up my horizons, every time I walk around my work, I think of her.” Magdalene Odundo

Two Temple Place, London WC2

29th January – 24th April 2022

Ladi Kwali

COURTESY: York Museums Trust (York Art Gallery) / PHOTOGRAPH: W. A. Ismay

LAST NOVEMBER, PHILLIPS sold what it called “the most important collection of contemporary ceramics ever to come to auction”, amassed by the art dealer and scholar John Driscoll. The top ten lots were, not unpredictably, all by Lucie Rie and Hans Coper, for whom a new auction record was set. It was one of 28 exceeded that day, none more spectacular than the £132,300 (including fees) realised by a water pot by the Nigerian potter Ladi Kwali. Its estimate had been a modest £6,000-£8,000. Hitherto the highest price commanded by her extraordinarily fine and exquisitely inscribed vessels had been £12,750.

Born in 1925, Kwali is hardly unknown. Her pots can be found in the collections of the British Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum. Her image graces the back of Nigeria’s 20 naira note. And she is not short of high-profile admirers.

Ladi Kwali, ‘Pot’, 1959

COURTESY: York Museums Trust (York Art Gallery)

The multi-media artist Simone Leigh has spoken of how “discovering a really beautiful water pot” by Kwali inspired her to become an artist. It made her “start to think about the means of production, the knowledge, everything that happens around that object” and informs the ways she sculpts life-size female figures in clay before casting them in bronze, works she will show at this year’s Venice Biennale, where she is representing the US with an exhibition dedicated, says its co-curator, Jill Medvedow, “to the experiences and contributions of Black women”.

Kwali also had a profound influence on the Kenyan-born British studio potter Magdalene Odundo, who trained with her in Nigeria in the 1970s, and who herself has held the record for the most expensive ceramic by a living artist since Sotheby’s sold a rounded pot with an elongated trumpet-like neck glazed in orange, brown and black for £378,000 last year.

Magdalene Odundo, ‘Group of pots’

COURTESY: © Magdalene A.N. Odundo & York Museums Trust (York Art Gallery)

“Ladi Kwali opened up my horizons,” Odundo has said. “Every time I walk around my work, I think of her.” They had no common language – Kwali spoke Hausa, Odundo Swahili – so it was a very physical training “like a mother teaching her baby to walk”. Kwali would hold her hand as she added clay to the pot she was building. “I literally mimicked her, as she had when she was learning from her aunt,” Odundo told the critic Jennifer Higgie. “I was in total awe of her.”

Magdalene Odundo, ‘Water Carrier (Esniasulo)’, circa 1974-76

COURTESY: © Magdalene A.N. Odundo & The Hepworth Wakefield, Wakefield Permanent Art Collection / PHOTOGRAPH: Lewis Ronald

This winter, a range of pots by Kwali will be shown alongside works by Odundo and six other artists in an exhibition in London entitled ‘Body Vessel Clay: Black Women, Ceramics & Contemporary Art’. In the words of its curator, Jareh Das, the exhibition both “reacts to a call to demystify Ladi Kwali” and explores “how ceramics have been disrupted, questioned and reimagined by Black women over the past 70 years”.

Phoebe Collings-James, ‘The subtle rules the dense’, 2021

COURTESY: © Phoebe Collings-James / PHOTOGRAPH: Paul Tucker

Das was a curatorial fellow at Middlesborough Institute of Modern Art [MIMA] in the north of England when she first read about the Pottery Training Center in Abuja, then a small town in northern Nigeria, where Kwali worked. The British ceramicist Michael Cardew, who trained with Bernard Leach, arrived there in 1951, a place his biographer, Tanya Harrod, describes as “a small paradisical emirate, especially if you were an expatriate”. (Now known as Suleja, it gave its original name to Nigeria’s modern capital in 1976.)

Its emir, Sulaiman Barau, was keen to facilitate education projects in collaboration with the colonial administration, among them a Pottery Training Centre that would train makers of traditional ceramics to produce, says Das, “casserole dishes, beakers, beer tankards and other everyday functional domestic tableware for the emerging Nigerian middle class.” Cardew, a government “pottery officer”, was appointed to set it up and run it.

Shawanda Corbett, ‘I’ll tell you what (From: Neighbourhood Garden)’, 2020

COURTESY: Shawanda Corbett and Corvi-Mora / PHOTOGRAPH: Marcus Leith

Ladi Kwali, meanwhile, came from a small village of Gwari Yamma people, about 30 miles away. “It was said that by the time she was a teenager, her pots would sell before they got to the market,” says Odundo. “And we know the emir collected her work,” adds Das, and that Cardew saw it in his house and was impressed by it, so though they hadn’t intended to employ women at the centre, she was invited to work there.

“The centre was male-led because [it was thought] men were stronger and would produce more,” says Das, who grew up in Lagos in the south of Nigeria. “But Ladi Kwali really disrupted that and made a way for other women – potters like Halima Audu – to come into the centre and train and work there.”

Magdalene Odundo, ‘Burnished jar with top flared on one side, red and black’, 1984

COURTESY: © Magdalene A.N. Odundo & York Museums Trust (York Art Gallery)

Here Kwali learnt to use stoneware rather than terracotta as well as western techniques such as glazing and wheel throwing, though she preferred to build pots by hand using the coiling method she had learned in her youth.

She also began to decorate them in sgraffitoed slip. “People ask me about the meaning of the animal motifs and folkloric figures,” says Das. “But they are rooted in Gwari, which is an oral tradition, and I come from a completely different ethnic group, so I don’t know. Kwali had tattoos on her arms and scarification on her face, and some people have asked if she translated those on to her pots, but I just don’t know that either. Although there’s a lot of documentation about her career, there’s not much around about her. It’s been quite a journey trying to piece together her life.”

Ladi Kwali, ‘Pot’, 1959 (detail)

COURTESY: York Museums Trust (York Art Gallery)

There is, however, a film of Kwali at work on Vimeo, “radiant with the fun of it all”, as Cardew observed, noting that when she was satisfied with a pot, “she would begin to sing”. As Harrod has written, watching her at work was “one of the world’s performative wonders […] To awed outsiders she appeared to go into a trance-like state as she incised outlines and cross-hatching with a knife-like tool, working her way round the pot without any preliminary setting out.”

Bisila Noha, ‘Water Vessel’, 2021

COURTESY: © Bisila Noha / PHOTOGRAPH: Paul Tucker

Odundo has also spoken of Kwali’s “dancing around” both pots she was making and those of her students. “Oh boy, it was amazing. She would point at the mistakes I had made. It was her eye, that ability to see form and to correct it. She had a sense of geometry in her bones.” Like Kwali, Odundo builds her pots using the coiling method, enabling her to create large sculptural forms evocative of the female body such as the 57cm-high ‘Asymmetric Vessel’ acquired earlier this month by the Hepworth Wakefield.

The physicality of Kwali’s making was also what drew Das to her work. “I’ve always been interested in the movements involved in hand-building, the way the body engages with it. There’s a real sort of dance around the object to create it.”

Jade Montserrat and Webb-Ellis, ‘Clay’ film still, 2015

COURTESY: Jade Montserrat and Webb-Ellis

Indeed, although all the artists whose work she has chosen to show work with clay, most of them – Phoebe Collings-James, Shawanda Corbett, Chinasa Vivian Ezugha, Jade Montserrat and Julia Phillips – have interdisciplinary practices, embracing drawing, sculpture, video, sound, text and performance. Only Odundo and Bisila Noha, who will also be one of 20 artist-makers to be featured at this year’s Harewood Biennial, can really be described as studio potters.

Vivian Chinasa Ezugha, ‘Uro’, a SPILL Commission at SPILL Festival 2018

COURTESY: Vivian Chinasa Ezugha / PHOTOGRAPH: Guido Mencari

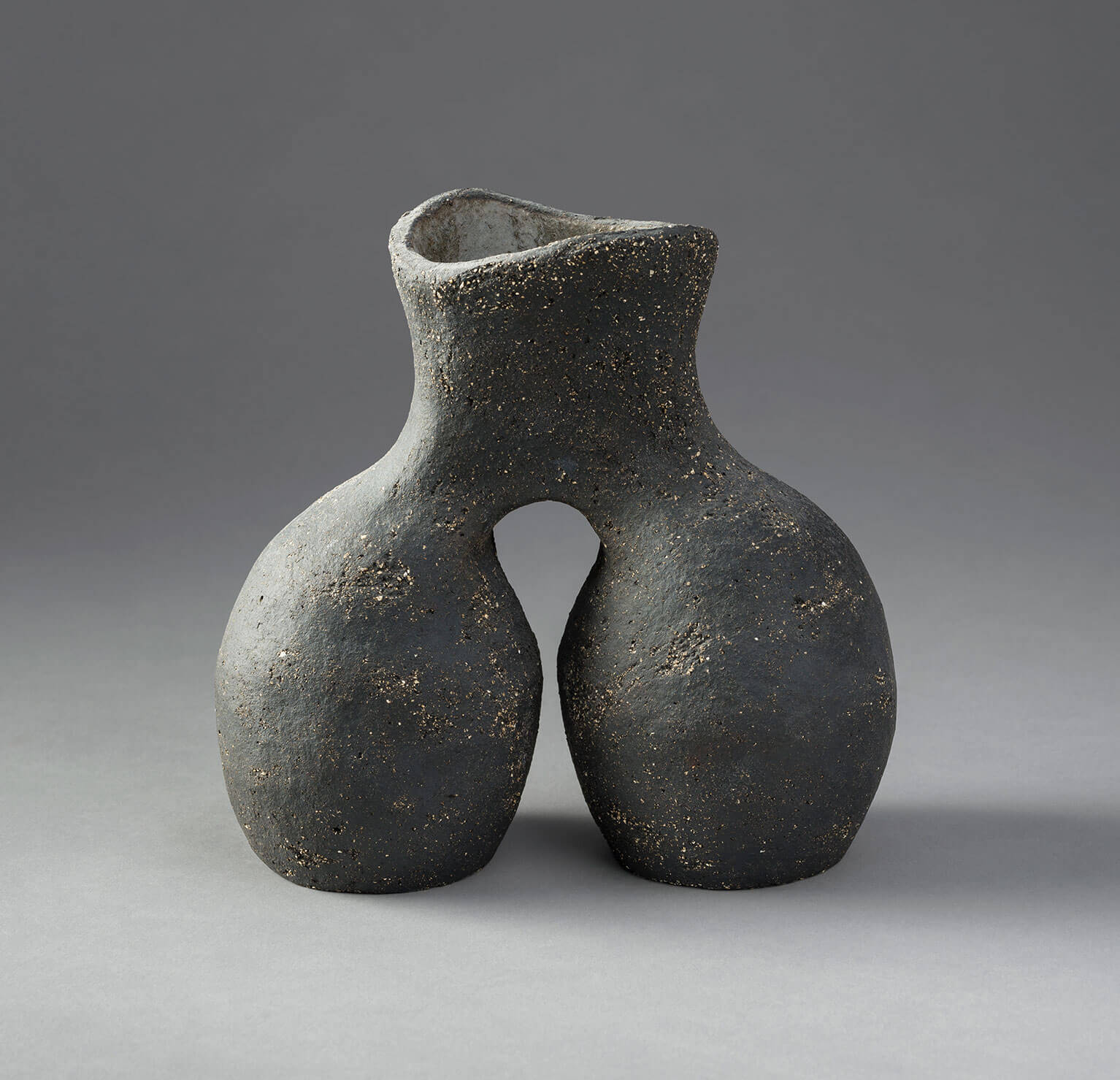

London-based Noha began to hand-build pots in 2020 (previously she had “mostly thrown”), using clay from Equatorial Guinea where her father comes from. “Since I couldn’t find anything about [Guinean] pottery, I looked at other traditions in Cameroon, Nigeria, Chad and Ivory Coast, searching for shapes,” she says, settling on what she believed were two universal shapes: the moon jar “and a two-legged vessel, which was a perfect way to reflect how I feel: a conjunction of two legs, two parents, two cultures [her mother is Spanish] and two races that combine and birth something new.”

Noha, ‘Two Legged Vessels’, 2020

COURTESY: Noha / PHOTOGRAPH: Thomas Broadhead for OmVed Gardens

The latter sold well. And it was only later she discovered the debt she unwittingly owed the Ivorian potter Kouame Kakaha. “I felt terrible like I’d betrayed another woman, a fellow potter, a sister.” Hence her decision to pay her tribute with her new project “the unnamed women of clay”, in homage to Kakaha and Kwali, Mama Aïcha from Morocco and all “our shared mothers and grandmothers” whose names have been “ignored, belittled and forgotten”.

Bisila Noha, ‘Kouame Vessel’, 2021

COURTESY: Bisila Noha / PHOTOGRAPH: Paul Tucker

“When one looks at African pottery – at the British Museum or in books – the pieces generally belong to a tribe.” The works are unattributed, their makers nameless. “We only know about Ladi Kwali,” she adds, “because Michael Cardew brought her into our consciousness, even though she had been making work since she was a young girl, learning from traditions that were part of her culture.”

Phoebe Collings-James, ‘The subtle rules the dense’, 2021

COURTESY: Phoebe Collings-James and Camden Arts Centre / PHOTOGRAPH: Rob Harris

Certainly, Kwali was known outside Nigeria during her lifetime. In the late fifties, she began to exhibit at and sell through the Berkeley Galleries in London, and her work was shown in Paris and the US too. “But I don’t know how much she benefitted personally,” says Das. Kwali had no children, and though Das tried to track down “existing family members, I couldn’t trace anyone. There’s no foundation or trust to manage her legacy. I’ve done the best I can and I hope the exhibition will spark something.” But for the moment, “All we have left are these objects.”

‘Body Vessel Clay: Black Women, Ceramics & Contemporary Art’ at Two Temple Place, London.

Ladi Kwali film on Vimeo.

Harewood Biennial, Harewood House, Leeds.