Charlotte Perriand

An exhibition exploring the legacy of a designer who kept collaboration, innovation and adventure at the heart of her work.

The Design Museum, London

19th June – 5th September 2021

Place Saint-Sulpice apartment-studio room recreation with Charlotte Perriand’s ‘Table extensible’, 1927, and ‘Fauteuil pivotants’, 1927

COURTESY: The Design Museum / PHOTOGRAPH: Felix Speller

AS A YOUNG Parisian creative in the 1930s, living a Bohemian life in a Montparnasse garret, Charlotte Perriand trained for weekend ski trips in her beloved Alps by working out on a flat 8th-floor rooftop. In an early brush with death, recorded in her autobiography, A Creative Life, she nearly went over the edge chasing a misdirected medicine ball.

To reach her playground she would stand on the lavatory seat to exit her bathroom through the skylight, before clearing the roof overhang with a rock-climber’s mantel move. This early familiarity with flat roofs and overhangs may have sowed the seeds for her signature architectural achievement more than 30 years later: the ‘Arcs’ 1600 ski village in her father’s native Savoy.

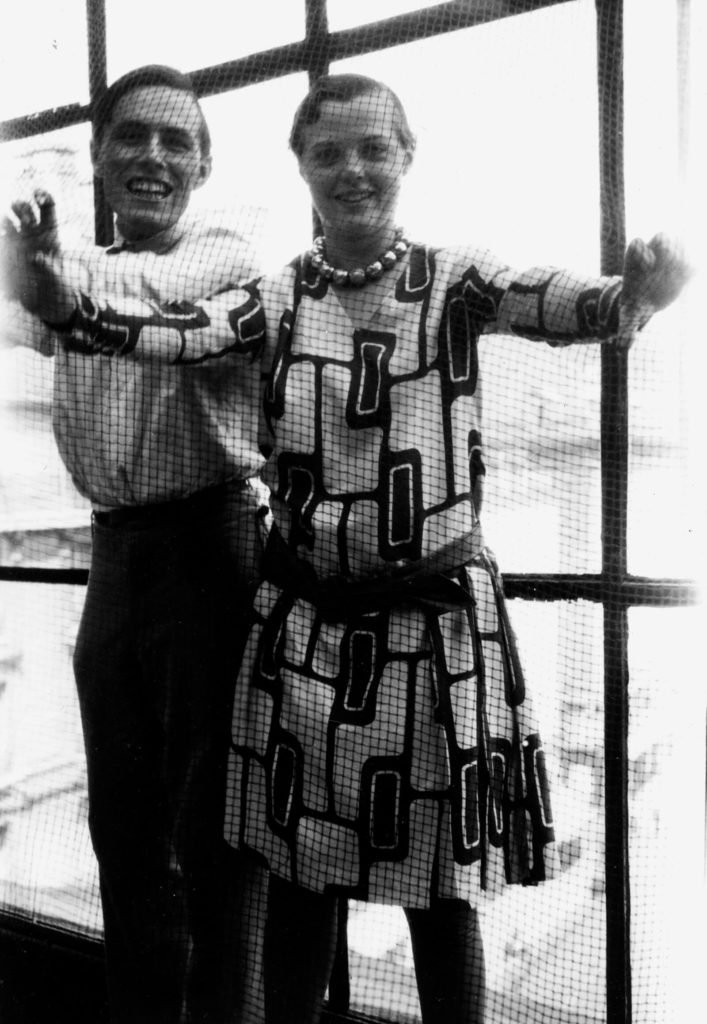

Charlotte Perriand with Alfred Roth in Place Saint-Sulpice apartment-studio, Paris, 1928

COURTESY: © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2021 / © AChP

A modernist in the machine age, Perriand didn’t do ‘pretty’. A rebel against her decorative arts training, she didn’t do ‘designer’; and ironically for somebody whose legacy creations include tubular steel chairs and a tilting lounger, she didn’t, in her own mind, do ‘furniture’. She did living spaces and the interior ‘equipment’ that made them habitable.

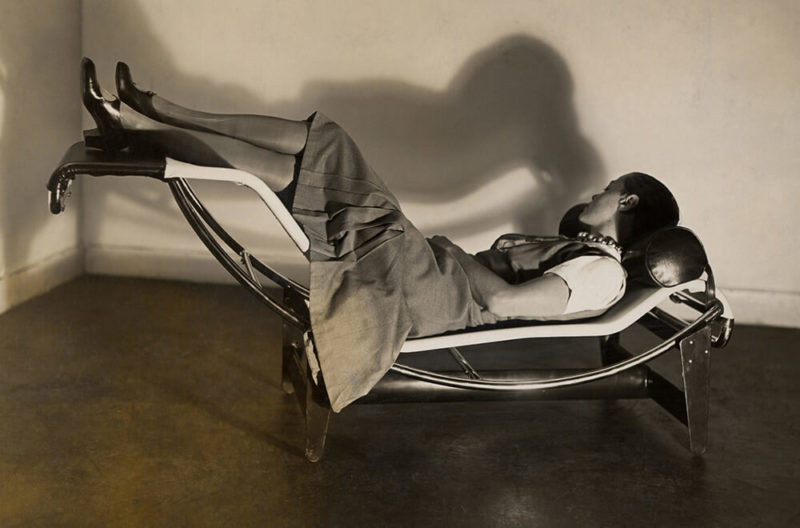

Charlotte Perriand, ‘Chaise longue basculante’, 1928 (produced by Cassina) in the recreation of the Salon d’Automne Salon d’Automne, 1929, by Le Corbusier, Pierre Jeanneret and Charlotte Perriand. Reconstruction by Cassina.

COURTESY: The Design Museum / PHOTOGRAPH: Felix Speller

For her, this equipment – chairs, tables, closets, bookshelves, kitchens and bathrooms – was not a furnishing afterthought. It was an integral part of the architectural process, up there with urban planning, materials science, structural engineering and industrial-scale production. Perriand believed that interior architecture was more than mere decoration, but should be a synthesis of design, architecture and art. “[It is this belief] that makes her maybe the most significant female designer of the 20th century,” says Justin McGuirk, Chief Curator of The Design Museum, where ‘Charlotte Perriand: The Modern Life’ is showing this summer.

View of the Place Saint-Sulpice apartment-studio room recreation

COURTESY: The Design Museum / PHOTOGRAPH: Felix Speller

Born into a century of conflicting -isms – imperialism, communism, fascism, nationalism – Perriand inevitably saw “a political dimension in architecture – regulating individuals and classes,” says the young French cultural commentator Alice Pfeiffer. “She paid attention to gender roles and reinvented women’s relation to domestic space. She created open kitchens adjoining living rooms, to literally and symbolically free housewives from a sense of isolation and allow them to take part in the home’s social life and conversations.”

Charlotte Perriand, ‘Cantilever bamboo chair’ and ‘Cross-based bamboo armchair’, 1940 (produced by Cassina)

COURTESY: The Design Museum / PHOTOGRAPH: Felix Speller

In a prolific career spanning seven decades and three continents, she created interiors for council flats and embassies, student dorms and ski lodges. Her wackiest creation was a mountain refuge shaped like a tin can on stilts. Her most commercial, the London ticket office of France’s national airline, Air France. But her most ambitious project unquestionably was the conception and greenfield development in the 1960s and 70s of the string of Alpine ski resorts known collectively as ‘Les Arcs’.

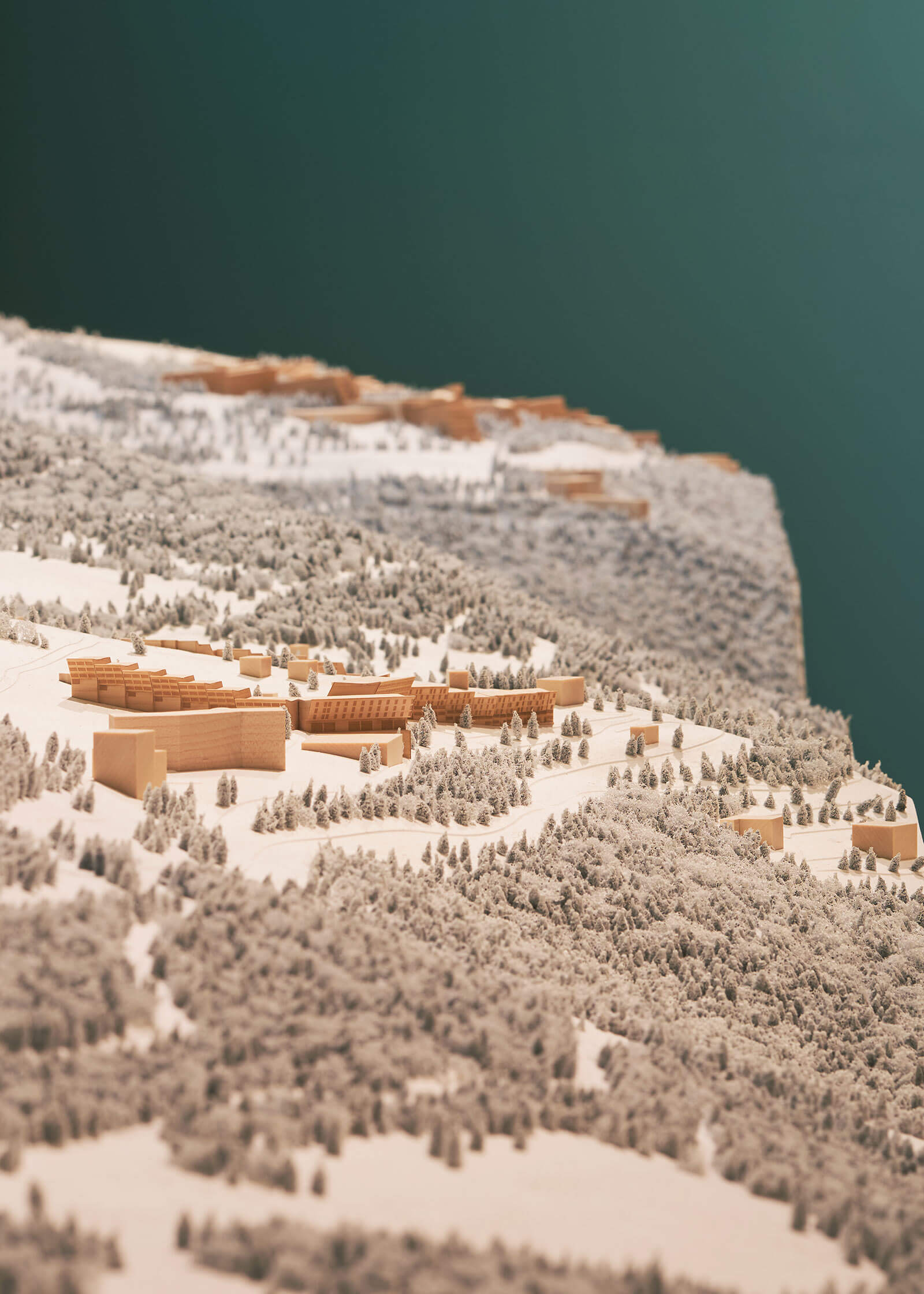

Relief model showing the locations of Arc 1600 and Arc 1800

COURTESY: The Design Museum & Fondation Louis Vuitton / PHOTOGRAPH: Felix Speller

The first of these, Arc 1600, particularly bore her stamp. Perched on a hillside above the little town of Bourg St Maurice, it looks for all the world as if a giant has knocked over and sat on a huddle of high-rise condo blocks. Some are squashed into the contours of the hill so that nothing shows except ranks of patio windows opening onto terraces, each terrace being the roof of the next rank down. Another, aptly named ‘The Cascade’, tumbles down the slope in a series of offset rhomboid cubes, configured so that on one side each apartment has a sunny balcony built on the ceiling of the apartment below, while on the other a corresponding overhang protects the access footpath and entrances from snow and rain.

‘La Cascade’, Les Arcs 1600, 1967-69

COURTESY: © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2021 / © AChP

It may be fanciful to sense her youthful insouciance sublimated in the out-of-kilter originality of these 1960s buildings; but go into one of the apartments and it’s certainly not fanciful to sense Japanese influences in their spatial conception.

In June 1940, as German armies bulldozed into France, Perriand sailed for Tokyo, which was not yet Germany’s ally, to take up a contract with Japan’s Ministry of Trade and Industry. She taught Japanese craftsmen modernist industrial design, the Bauhaus mantra that: “form emerges from function”. In return she absorbed the Taoist and Zen understanding of space: “The essence of a water jug is not its form, or matter, but the void that holds the water.”

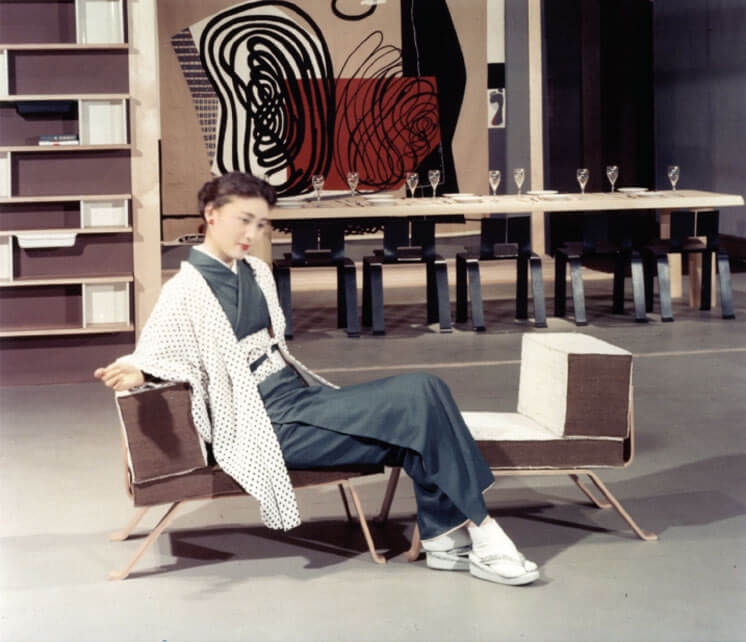

Charlotte Perriand, proposal for a Synthesis of the Arts, Takashimaya department store, Nihonbashi, Tokyo, 1955

COURTESY: © AChP/ © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2021

“Her time in Japan was a huge influence on her, as well as a proof of her adventurous spirit,” says McGuirk. He adds, “In Japan, two main things affected her: the quality of the craftsmanship; and the sense of domestic space – the importance of storage, the striving for that sense of productive emptiness.”

Charlotte Perriand, perspective drawing of the dining room in the Place Saint-Sulpice apartment-studio, Paris, 1928

COURTESY: © AChP/ © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2021

In a typical Arc 1600 apartment, the outer wall between living space and balcony is a sliding screen – made of glass and wood, rather than rice paper and bamboo, but still perfectly Japanese in conception. Less a barrier than a transition integrating the few square metres of interior into the limitless beyond.

Storage space takes the form of a set of cupboards fronted with slatted, lightweight doors in local pinewood: plain and unobtrusive. The kitchen area is integrated into the living space. Perriand designed kitchen units and bathrooms which consisted of formed-metal modules, prefabricated off-site and slotted into place, a radically original application of industrial production techniques. “It’s innovative for her time,” comments McGuirk, “normalised modules which can be put up in multiple ways. It makes the user part of a collaborative process.” McGuirk adds, “The originality of her ideas is often overlooked – [for instance,] the idea of furniture as an architectural space divider, something she carries through her career.”

Charlotte Perriand, ‘Bookcase for the Maison du Mexique’, 1952

COURTESY: © AChP/ © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2021

Before the war and Japan upended her life, Perriand had worked for a decade with Le Corbusier, proselytiser of the house as “lived-in machine”. After the war, she worked with Jean Prouvé, visionary innovator of pre-formed steel sheet construction. Both collaborations are bound into the DNA of Les Arcs, together with others, such as the local master craftsman in wood construction, Roger Taillefer.

“One crucial advantage Perriand had over Le Corbusier was that she cared about the people that used her buildings, whereas le Corbusier considered buildings abstractly,” says Sarah Wigglesworth, an award-winning London architect focused, like Perriand, on sustainable, people-centred design. “She was clearly committed to most people’s social and economic realities, and how mass production with simple craft-based familiar products could answer to this.” Adds Pfeiffer, “For Perriand, modernism was more than a style, it held the promise of a more egalitarian society. Her career and life choices were a sort of manifesto against Western patriarchal domination.”

Charlotte Perriand, ‘Double chaise longue’, 1952 (produced by Cassina); ‘Nuage’ bookshelf, Steph Simon edition, circa 1958. Reconstruction by Cassina.

COURTESY: The Design Museum / PHOTOGRAPH: Felix Speller

In a world where women were expected to be homebodies, and architecture was mostly the domain of self-promoting men, her interiors were “not designed to be collectible,” McGuirk says. They were designed to be lived in, and affordable. Perriand was designing for every man – and every woman – in an emerging mass popular market.

Charlotte Perriand, ‘Shepherd’ stool, circa 1948 (Estimate €1,000 – €1,500. Unsold.)

COURTESY: © Ivoire Toulouse/Primardeco

It’s this every day, lived-in quality of her work that now attracts collectors, says auctioneer Jérôme de Colonges at Primardeco in Toulouse, who this month (June 1st) sold a collection of six Perriand chairs, a dining room table and three stools from a 1970s-built family home. The plain solid wood table, scuffed and scratched by five decades of use, sold for €58,700 euros, nearly double the top end of its €20,000-30,000 estimate, while the straw-seated, plywood-backed ‘Meribel’ chairs went for more than €8,000.

Charlotte Perriand, ‘Méribel’ chairs, circa 1946. (Estimate €2,000 – €3,000. Sold for €8,250)

COURTESY: © Ivoire Toulouse/Primardeco

“This is furniture which served the everyday life and comfort of a family,” Colonges said, “it has a patina.”

“Perriand put utility and beauty in reach of everybody. This table is so simple, so pure – but it is a simplicity that’s the refined product of a great deal of complexity.”

“I suppose the buyer may pay to have it restored and turned from everyday utility into an artwork,” Colonges mused: “in which case Charlotte Perriand will be in some sense a victim of her own success.”

Charlotte Perriand: The Modern Life is showing at The Design Museum, London.