Design Week Lagos

The dynamic Nigerian city hosts the rising design stars of West Africa – soon to be viewed by an international audience via a Netflix documentary.

Lagos

October 21st-31st,2021

Titilailai Design Studio, ‘Comb’ chair, 2021

COURTESY: Titilailai Design Studio

NIGERIAN DESIGN MAVEN Titi Ogufere wears many hats, from having established the Interior Designers Association of Nigeria (IDAN) to being the first president of African descent of the International Federation of Interior Architects/Designers (IFI) – not forgetting her role as creative director in the Lagos-based design agency, Essential Interiors Consultancy.

While Ogufere has geared her entire decade-long practice towards promoting design in Nigeria and West Africa, her most personal endeavour has been creating Design Week Lagos (DWL) in 2019. As the new iteration of the ten-day event – the largest of its kind in Western Africa – continues across the Nigerian metropole until 31st October, Ogufere tells The Design Edit that DWL stemmed from a lack of global recognition of the country’s design potential. “I made it my mission to unite the community, harness talent and build industry – to show the world the exciting, relevant work happening here,” she says.

Ike Studio, ‘Oche Bench’, 2021

COURTESY: Ike Studio

The current edition, titled ‘Design Revolution’, echoes the pre-pandemic vivacity of the inaugural affair, with an exhibition of fifteen designers and studios, the virtual IFI African Regional Roundtable discussion with the participation of over 5,000 African designers, and a student prize for a solution-based design competition. Unique to this year, however, is the premier of the Netflix docu-series Made by Design, about Nigerian design. This new development had evolved from the pandemic, which had put DWL on hold and prompted its organisers to think digital.

Tekura, ‘Chair’, 2021

COURTESY: Tekura

Made by Design’s first season highlights a total of thirteen industrial or product designers, as well as architects – among whom are Osaru Alile, Lani Adeoye, Depo Akintunde, Papa Omotayo and Theo Lawson – based across Nigeria. Ogufere, who co-produced the series with Emmy award winner filmmaker Abiola Matesun, is hopeful that the show, similar to DWL, will prompt further attention to the country’s vibrant creative profile. “There is such an incredible range of talent here that the series only really scratches the surface.”

Josephine Forson of Tekura

COURTESY: Tekura

A critical curatorial thread of DWL is dismantling what Ogufere sees as an, “extremely reductive global understanding of African design, inextricably linked to a history of colonialism.” She gives the example of the Ankara fabric, which is often considered African yet is of Dutch creation, imported to the continent after it failed to sell in the Philippines.

Achinivu Okorafor for Opoto Design, ‘Okpo’koro’, 2019

COURTESY: Achinivu Okorafor

Ogufere notes the undeniable connection between the history of western Modernism and traditional African design. “African design traditions are the root of Modernism – they are natural, neutral colours, with clean lines and geometric patterns that hold great significance both in their reference to the land and its history.”

Studio Osaru Alile’s ‘Wrap’ chair is an object of historical and personal resonance, both for her native Benin and the family legacy. Alile had fallen in love with the “craftsmanship, upholstery and vibrancy” of her grandparents’ furniture from the 1950s. “This stirred up a deep desire in me to have a soulful understanding of the stories behind them,” she adds.

Osaru Ailie, ‘Wrap Chair’ for 7Eight Pieces, 2021

COURTESY: Osaru Ailie

The resulting chair is a hybrid of traditions, symbols and craft techniques: artist Osaru Obaseki designed the print for the cotton fabric, which was spun in Funtua, while the batik was hand-dyed by Oyinkansola Olatunde in the state of Osun. The symbols on the cloth represent the various aspects of the Benin culture with a focus on authority, spirituality and the value of life. Alile’s Lagos-based firm, CC Interiors, has been part of DWL since its inception, and is showcased in the Netflix docu-series.

Osaru Ailie, ‘Wrap Chair’ for 7Eight Pieces, 2021

COURTESY: Osaru Ailie

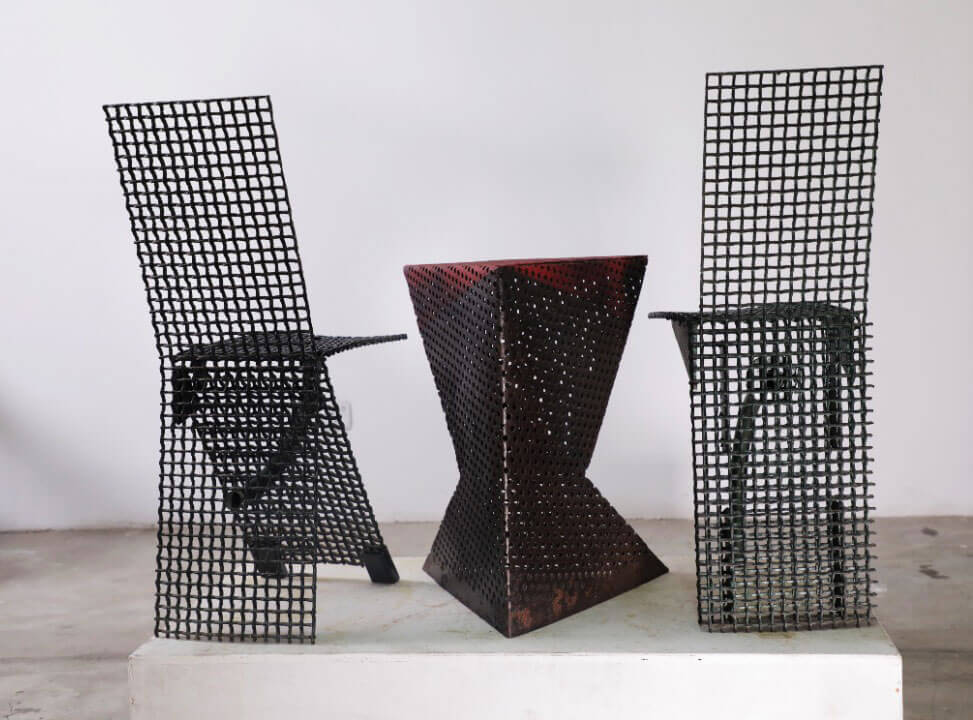

Sculptor and designer Olu Amoda’s chairs ‘Flip’ and ‘Balance’, and the side table, ‘Akaba’, are a result of Amoda’s exploration of his connection with the users of his objects. “A chair supports comfort, but sitters occasionally like to check the material’s structural integrity,” he explains about ‘Balance’. The salvaged steel chair is constructed in the form of a grid and supported by a bent rod leg.

Olu Amoda, (left to right), ‘Flip’, 2003, ‘Akaba’, 2004-2019; ‘Balance’, 2003

COURTESY: Olu Amoda

“It is fun seeing sitters realise the precarious situation of restlessness and extend their feet apart to give extra support to prevent [themselves] tipping over.” He sources his materials from Lagos’s Owode Onirin and Orile scrap markets where tons of discarded design products wind up. Amoda calls his searches at the markets, “treasure hunt trips,” and adds: “Each visit is like an anthropological, forensic and archeological field trip: they reveal the attitude and taste of its owner, evident in the discarded objects.”

Nifemi Bello, ‘Chair’, 2018

COURTESY: Nifemi Bello

For Nifemi Bello, industrial design is a tool for humorous connection, which he achieves through the “element of surprise in functionality or materiality.” Bello gives his ‘LM Stool’ as an example of “luring people in via material, texture or colour.” The quirky seat’s unassuming weight is hidden behind its thin form and singular colour – prompting amused reactions when people discover its unexpected density. The comments have confirmed Bello’s interest in the emotional reality of using an object and triggered understanding about the performativity of design. “People say they love the weight of the chair, as if this also compliments the overall design. I would be lying if I say I saw this coming, but I have learnt so much from that in itself.” This realisation guides the designer towards lighthearted yet intricately-envisioned strategies. “Depending on the context of the brief, I don’t take myself too seriously, because I think design can be fun and intellectual at the same time,” he says.

AGA CONCEPT, ‘Mnanwu Chair’, 2021

COURTESY: AGA

“Lagos is an incredibly dynamic city in terms of design and culture,” summarises Ogufere. “DWL provides an incredible moment to access the creative energy of the city, a moment for the community to come together, to share and convene with their peers – and see what is happening beyond the silo of their studio.”