LDF / Discovered

Promoting twenty young designers and the merits of American hardwood.

Exhibition view

COURTESY: The Design Museum / PHOTOGRAPH: Thom Atkinson

IT HAS BEEN incredibly tough to forge a new career over the past 18 months. In the design world, graduates have seen many of their traditional platforms vanish. New Designers, which is traditionally held annually at the Business Design Centre in Islington during July, migrated online this year after being cancelled in 2020, for instance. Meanwhile, many of the universities’ own shows have been severely abridged. To compound the issue further, trade fairs and global design festivals, which fertilise up-and-coming talent, have been postponed or run as smaller, more obviously local, iterations. Which is where the American Hardwood Export Council (or AHEC, for short), in collaboration with Wallpaper* magazine, decided to step in.

Juan Franco & Juan Sierra, ‘Riverside’, 2021

COURTESY: Juan Franco and Juan Sierra & The Design Museum / PHOTOGRAPH: Jason Yates

Discovered, which opened at the Design Museum on 13th September, brings together 20 emerging designers from around the world to create a piece of furniture, or an object, that investigates their relationship with ‘touch, reflection and strength’ during the COVID crisis. Among other things, the brief asked them all to think about coping with isolation and the changing relationship between the physical and digital at a time when so many people have been forced to communicate through Zoom. The only real stipulation was that they had to work with one of four timbers from the American hardwood forest – red oak, American cherry, and hard and soft maple.

The designers were split into four groups, along broadly geographic lines, and each group was allocated a mentor, an experienced designer who could help refine their thinking and guide them through the process. Subsequently, their ideas were made in four workshops – Benchmark in the UK, WeWood in Portugal, Australia’s Evostyle and Fowseng in Malaysia.

Making of ‘Howard Desk’ by Mimi Shodeine

COURTESY: The Design Museum & Mimi Shodeine / PHOTOGRAPH: Fraser Stephen

“The project is so important for us,” confirms AHEC European director David Venables, “because it’s about the next generation of talent. It’s a group that has had a real challenge already and will face significant challenges in their working lives.” And he’s quite right, inevitably nascent careers have been stymied.

Alessandra Fumagalli, sketches of ‘Studiolo 2.0’, 2021

COURTESY: Alessandra Fumagalli, The Design Museum, AHEC & Wallpaper*

“Graduates, and those who are still emerging in their careers, have had very little chance to engage with makers,” explains Benchmark’s co-founder Sean Sutcliffe. “It will be pretty challenging for them to make up lost ground.” For several of the designers, the project came at an opportune time. “It has been very tough,” Alessandra Fumagalli Romario, tells me from her home in Milan. “I’d just finished studying [at the Royal College of Art], so it was the year of starting real work. The idea was to find a job and start my career but everything was very difficult.”

Alessandra Fumagalli Romario, ‘Studiolo 2.0’, 2021

COURTESY: Alessandra Fumagalli & The Design Museum / PHOTOGRAPH: Jason Yates

And while many have been able to work digitally, they still lack that human element of seeing their pieces being made in a workshop. “It’s about the ability to communicate face-to-face. I still utterly believe that the best designs come from hands-on experience and the best designers know how stuff goes together,” says Sutcliffe. “Stuck at home they all miss the studio interaction and the lack of serendipity – that moment where someone says the right word over your shoulder and turns on a lightbulb for you.”

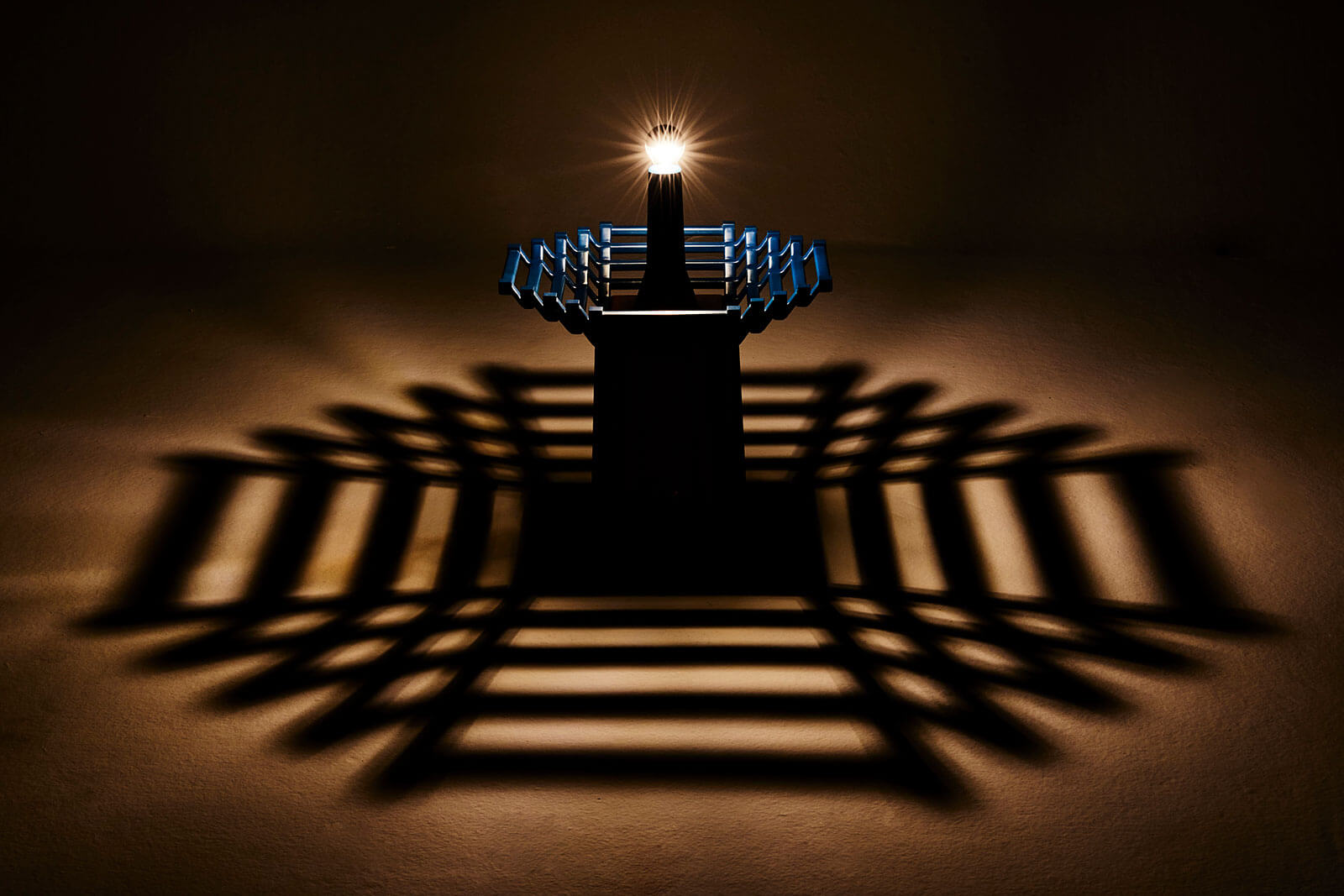

Kamonwan Mungnatee, ‘Corners Lamp’, 2021

COURTESY: Kamonwan Mungnatee & The Design Museum / PHOTOGRAPH: Winston Chuang

Kamonwan Mungnatee, ‘Corners Lamp’, 2021

COURTESY: Kamonwan Mungnatee & The Design Museum / PHOTOGRAPH: Winston Chuang

Bearing these constraints in mind, it’s fascinating to see that the finished results run design’s gamut: from the rational to the playful and from the functional to the sculptural. German designer Pascal Hein, who currently works in Konstantin Grcic’s studio, has created ‘Migo 01’, a fascinatingly zoomorphic chair which can be used in a number of ways, for example. “There’s no front or back. There’s no right or wrong. Yes, it’s a chair and you can sit on it but you can sit on it in various ways. You can adapt to it or it can adapt to your needs,” he explains. Not only that but the user can perch on it or it can also act as a side-table.

Pascal Hien, ‘Migo 01’, 2021

COURTESY: Pascal Hien & The Design Museum / PHOTOGRAPH: Jason Yates

Ultimately, he says, the piece is an attempt to combat loneliness: “It’s a companion or a friendly little helper. What I wanted the object to be is something that has a presence. I wanted to create something that you can have a relationship with. I didn’t want it to be a passive object. I wanted it to be like a buddy.” Each of the pieces in the collection comes from a single plank of red oak, ensuring an aesthetically pleasing consistency of grain. It’s a very smart design that you could easily imagine going into production.

If Hein’s piece was designed to combat isolation then, conversely, Martin Thubeck used his experience of being cooped up with his young children in a small flat to playful effect. Flip the Stockholm-based designer’s chair over and it transforms into a small slide, ideal for the kids.

Martin Thubeck, ‘Ra’, 2021

COURTESY: Martin Thubeck & The Design Museum / PHOTOGRAPH: Jason Yates

As he explains: “The idea was born from a curiosity of asking: ‘Why not?’ I figured what would happen if the children became part of my work?” It’s a surprising, genuinely joyful piece of thinking.

Martin Thubeck, ‘Ra’, 2021

COURTESY: Martin Thubeck & The Design Museum / PHOTOGRAPH: Jason Yates

Several of the cohort from South East Asia took the opportunity to emphasise their local culture at the behest of their mentor, Nathan Yong. “I did hint to them that they should look at their society and their architecture,” the Singapore-based designer says. “This project gives them an international platform.” Taking him at his word, Mew Mungnatee took her cues from pagodas in Bangkok, whilst Nong Chotipatoomwan was inspired by Thailand’s triangular cushions.

Nong Chotipatoomwan, ‘Thought Bubble’, 2021

COURTESY: Nong Chotipatoomwan & The Design Museum / PHOTOGRAPH: Winston Chuang

Nong Chotipatoomwan, ‘Thought Bubble’, 2021

COURTESY: Nong Chotipatoomwan & The Design Museum / PHOTOGRAPH: Winston Chuang

Intriguingly, the Singaporean designer, Tan Wei Xiang, looked to the building sites that pock his city. “I was kind of struggling,” he confesses. “Countries like Thailand and Japan have such a rich history, but the Republic of Singapore is less than a century old.” To work out what he should do he decided to take some long walks. It turned out to be quite a revelation. “The more I walked, the more I realised that I was looking at things I didn’t really want to see or hear – the construction sites of Singapore. So my piece is about the ever-changing landscape of Singapore’s environment. We are such a small country and yet we are rapidly developing our land. It looks totally different than it did five years ago.”

He describes the building sites as Singapore’s “new vernacular”. And as a result, his cabinet, made from hard maple, adroitly reflects the crinkled, green metal fences that surround them.

Tan Wei Xiang, ‘Recollect’, 2021

COURTESY: Tan Wei Xiang & The Design Museum / PHOTOGRAPH: Winston Chuang

As well as supporting a new generation of talent, AHEC is keen to use Discovered to talk about the sustainability of its material. Wood, after all, is a renewable resource that locks in carbon. It’s important to point out that chopping down older trees in order to manage woodland is not a bad thing – selective harvesting opens up the canopy of the forest, letting light in and encouraging young saplings to grow and to continue sequestering carbon. “Discovered is a platform for us to show how wood is a solution towards mitigating climate change,” says Venables. “We’re keen to make sure that a young generation thinks more deeply about those issues.”

The project is also a showcase for a selection of woods that are currently unfashionable. It sets out to prove they could have a market, which in turn would help use the American hardwood forest – that runs from Maine in the north down to Mississippi in the south – to its full potential. “The biodiversity of our global forests is huge,” continues Venables. “For the American hardwood forests it has become quite a critical issue because they are one of the most spectacular examples of reforestation that has happened over the last century. But in order to maintain that sustainability you’ve got to encourage the use, harvest and value of all the timbers, not just picking one or two species that certain designers or brands feel is the right look.” According to Sutcliffe: “[Many of the] architectural studio[s] are all wanting to talk wood. Sustainability is the single biggest reason – every 1kg of wood contains 1.8kg of stored carbon dioxide. As a carbon lock it is the best material. And the more wood we can get into our built environment – whether it’s the building structure, the interiors, the furniture – the better the sustainable performance of the building.”

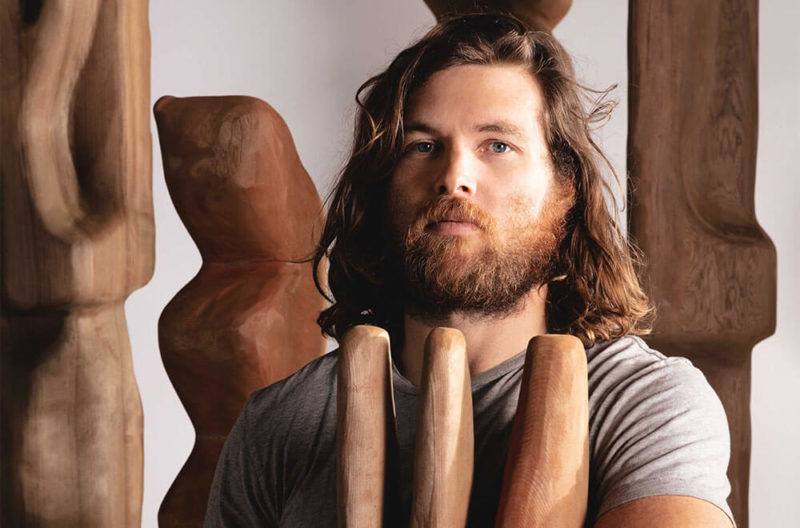

Mac Collins, ‘Cherry’, 2021

COURTESY: Mac Collins & The Design Museum / PHOTOGRAPH: Jason Yates

Discovered then is a gumbo full of different flavours. It’s a showcase for some of the industry’s best young talent from around the world – including Mac Collins, winner of this year’s London Design Festival Emerging Design Medal – it emphasises the importance of provenance and mentorship, and it provides a much-needed platform after a traumatic 18 months. That in itself is laudable, of course. But its subtly didactic element, which talks about sustainability and the need for bio-diverse forests is just as vital. This is design that’s really trying to make a difference.

Discovered: Designers for Tomorrow at the London Design Museum runs until 10th October 2021.