Fred Baier: form swallows function

He was one of the first designers to embrace computer modelling and CAD, thirty years on he's still on his journey.

New Art Centre, Roche Court, Wiltshire

23rd January – 10th April 2021

Fred Baier

PHOTOGRAPH: Sarah Weal

“WHEN I STARTED doing what I was doing, there was no outlet for somebody who made arty-farty furniture,” the designer Fred Baier tells me, over Zoom, tiny angel wings of white hair flying behind his ears. Baier was a pioneer – both in the field of furniture that aspired to be art and in the use of computers to realise those pieces. He began his experiments in the 1970s and has continued to pursue his own idiosyncratic vision for over forty years. With his defiant, anti-modernist credo – form swallows function – he has made a continuous stream of one-off inventions, each full of wit, imagination and wizard engineering.

This month the New Art Centre at Roche Court, near Salisbury, is mounting the first public show of Baier’s work for ten years. The works, dating from the 1980s to 2010, are placed through The Design House, with one piece, the ‘Love-Seat’, given pride of place in the eighteenth-century Orangery. Currently on view online, when government regulations allow, the show will open for visitors.

Fred Baier, ‘Rockin Bowl’, 2010

COURTESY: New Art Centre

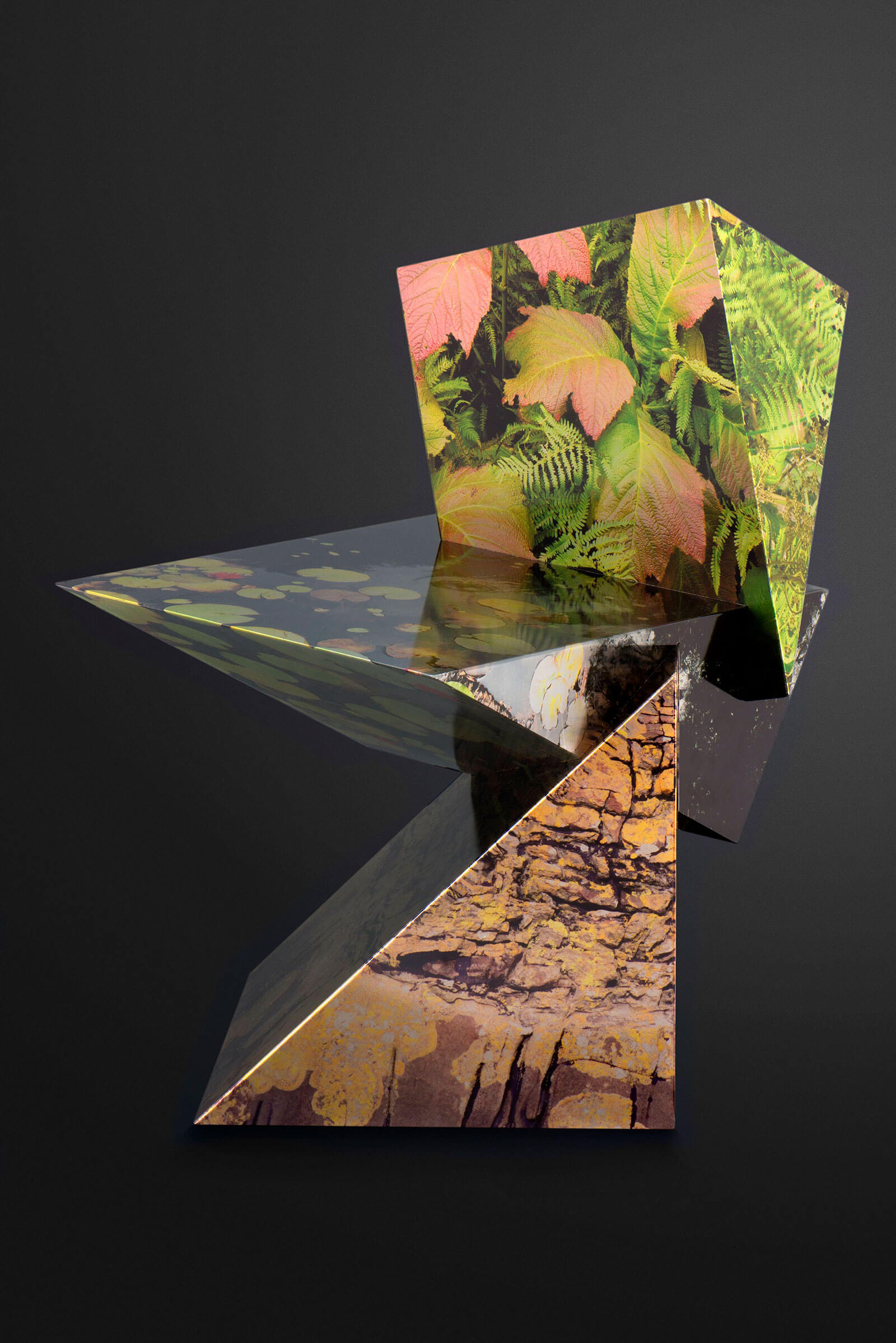

When the V&A bought his piece ‘Prism’ chair (1989/1993), a combination of three prismatic solids interpenetrating at unconventional angles, ahead of a 2011 exhibition about Post-Modernism, the curator, Glenn Adamson, spoke of Baier as “the most interesting British furniture maker of his generation.” As well as playing a critical creative role, alongside his friend Paul McManus, in the development of CAD (Computer-aided design), Baier has also been a hugely influential teacher, both through courses he has taught at the Royal College of Art and through mentoring younger designers like Gareth Neal, Tim Wells, Rachel Hutchinson and Mike Wainwright, who have worked as interns in his studio. Besides his own body of characterful works, his enduring relevance, according to Roche Court curator Sarah Griffin, lies in his ability to inspire “young minds to turn ideas into three dimensions.”

Fred Baier, ‘Park Life (Prism Chair)’, 2017

COURTESY: Mark Somerville

It was Baier’s woodworking teacher at school who tipped him off that if he wanted creative freedom, as a craftsman, he would have to go to art school. So Baier talked his way into Birmingham, School of Art, before going on to do an MA at the Royal College of Art (1972-1975). While at Birmingham, he worked at a near-obsolete pattern makers for the automotive industry, at a time when car parts were moulded not welded. “I loved the machines and the processes,” he explains, “In fact my final piece at the RCA, a chest of drawers, was a homage to the pattern-making industry.” To begin with he “made objects that were about the demise of the old way of crafting things.”

Installation view

COURTESY: New Art Centre

The other ingredient was a free and wild way with colour: “I had this idea that if you make attention-seeking objects, then they publicise themselves. So that’s what I started to do. I used bright colours, and I used a vocabulary of imagery that was unexpected – objects that looked like they might work, like a table with hydraulic pistons, or a baby’s cradle that looked like one of those crane grabs, or a bed that looked like the flat bed of a truck.” Baier adds, “It was a very free and expressive time. People were making Pop Art, Warhol had just had a show at the Tate. People were making things that looked like other things but you could sit on them.” In 1979 he was invited to exhibit at the Ikon Gallery in Birmingham, in a show titled ‘Furniture … Sculpture’, alongside sculptors Helen Chadwick and David Nash.

Fred Baier, ‘Pyramid Chairs’, 2014 (designed 1978/9)

COURTESY: Mark Heathcote

Gradually, Baier began to introduce the idea of movement to his pieces: “I was trying to make objects that embodied action, so ‘folding’, ‘piercing’, ‘balancing’, ‘pirouetting’, because I thought the body and ballet gave a dynamic to the work.” At this point Baier landed a commission from Phil Manzanera of Roxy Music, to design furniture for the Art Deco masterpiece, St Ann’s Court, designed in the 1930s by Raymond McGrath. He decided that rather than adopt an Art Deco aesthetic, he would follow their first principles, which were “to use the latest equipment and modern materials, and embody all these new materials and processes in the work”. The latest thing for Baier were computers. As he explains, “Computers had just stopped being green backgrounds with yellow writing on them, which you bought as a kit in a shop. The more sophisticated ones were making images, albeit with machines that had reel-to-reel tapes and men in white coats with stethoscopes, listening at the cabinets.” At first, Baier used the computers just to design, enabling him to work with geometries hard to conceive on paper. He would then build by hand.

Fred Baier

PHOTOGRAPH: Sarah Weal

“What drives all his work is his vivid imagination, his love of machines and his fascination with mathematics …”

Fred Baier

PHOTOGRAPH: Sarah Weal

” … He starts with the idea in his head, playing about with form before he even considers function”

In parallel, Baier began to explore his own version of a contemporary Baroque: “One of the major things about Baroque was that you had to make your resistant materials look like they flowed like silk or that they flapped in the wind. Everything had to be very fluid and ornate. You made hard objects that looked soft. So I made things like that.” By now Baier’s work was diverging outrageously from the new 1980s orthodoxy of a return to craftsmanship. As he puts it, “Here everyone was showing off their woodworking skills, whereas in the States people were getting hold of wood and getting in there with grinders and it wasn’t about woodwork, it was about making fluid objects out of things.” So Baier went to America and exhibited in New York, where he met Wendell Castle, the archduke of fluid, who invited him to teach at the Rochester Institute of Technology.

-

Fred Baier

PHOTOGRAPH: Sarah Weal

-

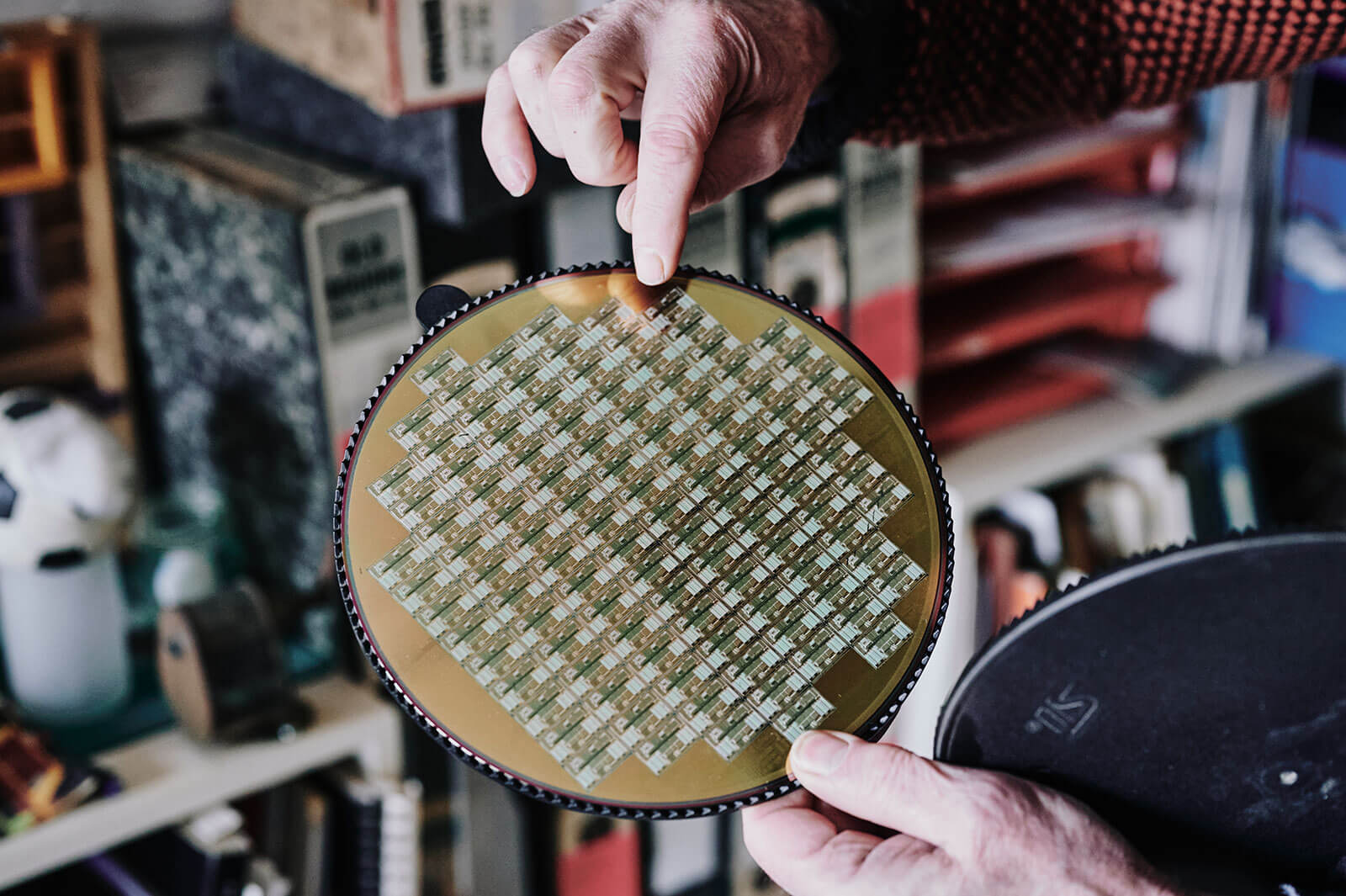

Computer circuit board

PHOTOGRAPH: Sarah Weal

-

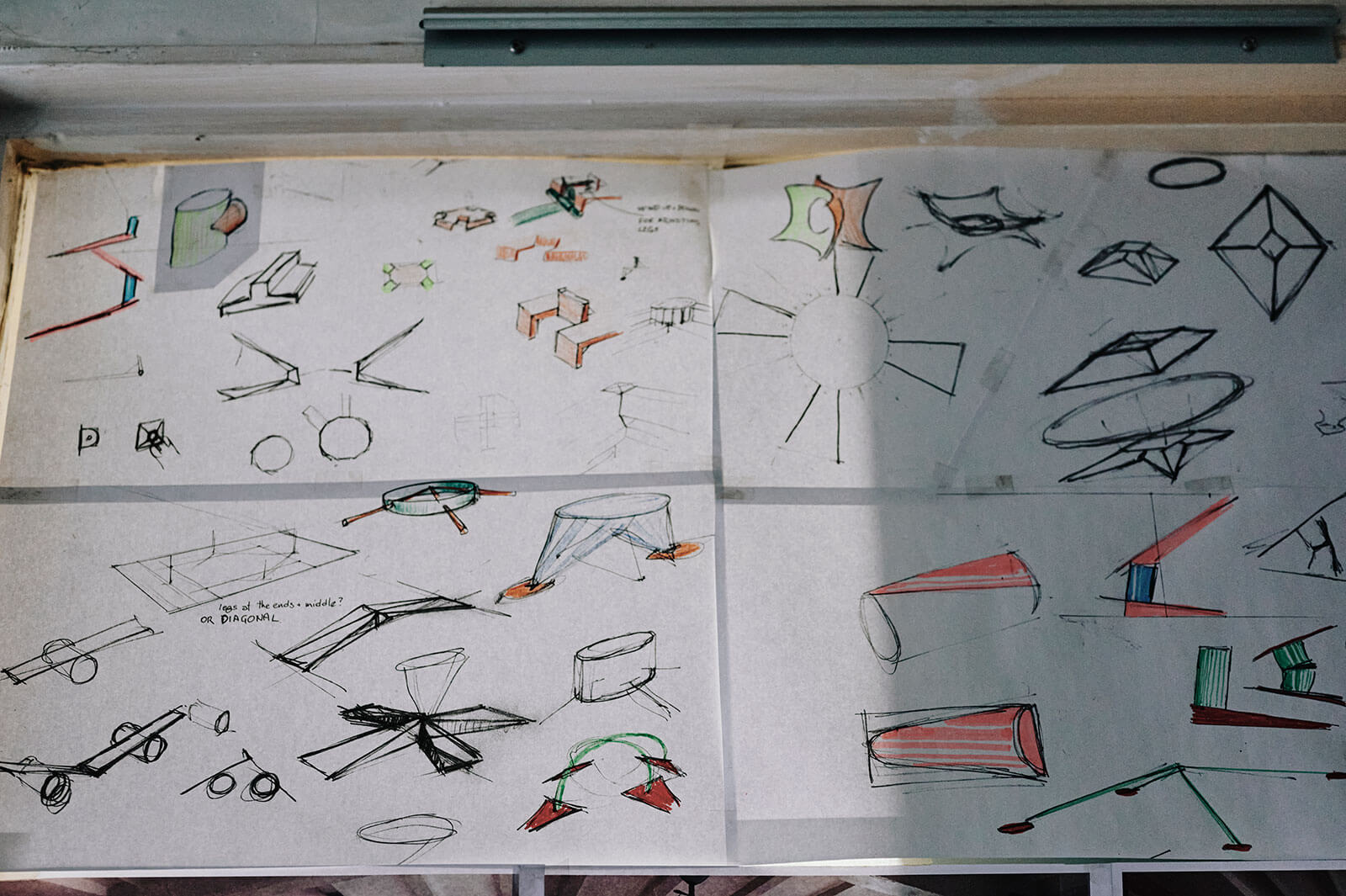

Sketches

PHOTOGRAPH: Sarah Weal

-

Workshop models

PHOTOGRAPH: Sarah Weal

-

In the workshop

PHOTOGRAPH: Sarah Weal

By the time he returned, computers had grown up. Together with the coder Paul McManus, Baier began to apply the computer to the actual putting together and building of the pieces, sitting beside McManus as they painstakingly worked out the language. Baier laughs, “I was Fred Flintstone. He was my Barney.” One of the pieces on show at Roche Court, the ‘Love Seat’, was conceived using a computer programme in 1982, and then built by a computer in the early 1990s. Baier comments, “This was probably one of the first things that was designed, developed and then manufactured using CNC.” The ‘Prism’ bought by the V&A, and its various siblings, is made using CNC folding and laser cutting and other computer technologies. Although conceptually constructed simply, in Baier’s words, ‘from lumps of geometry’, it is fiendishly difficult actually to build.

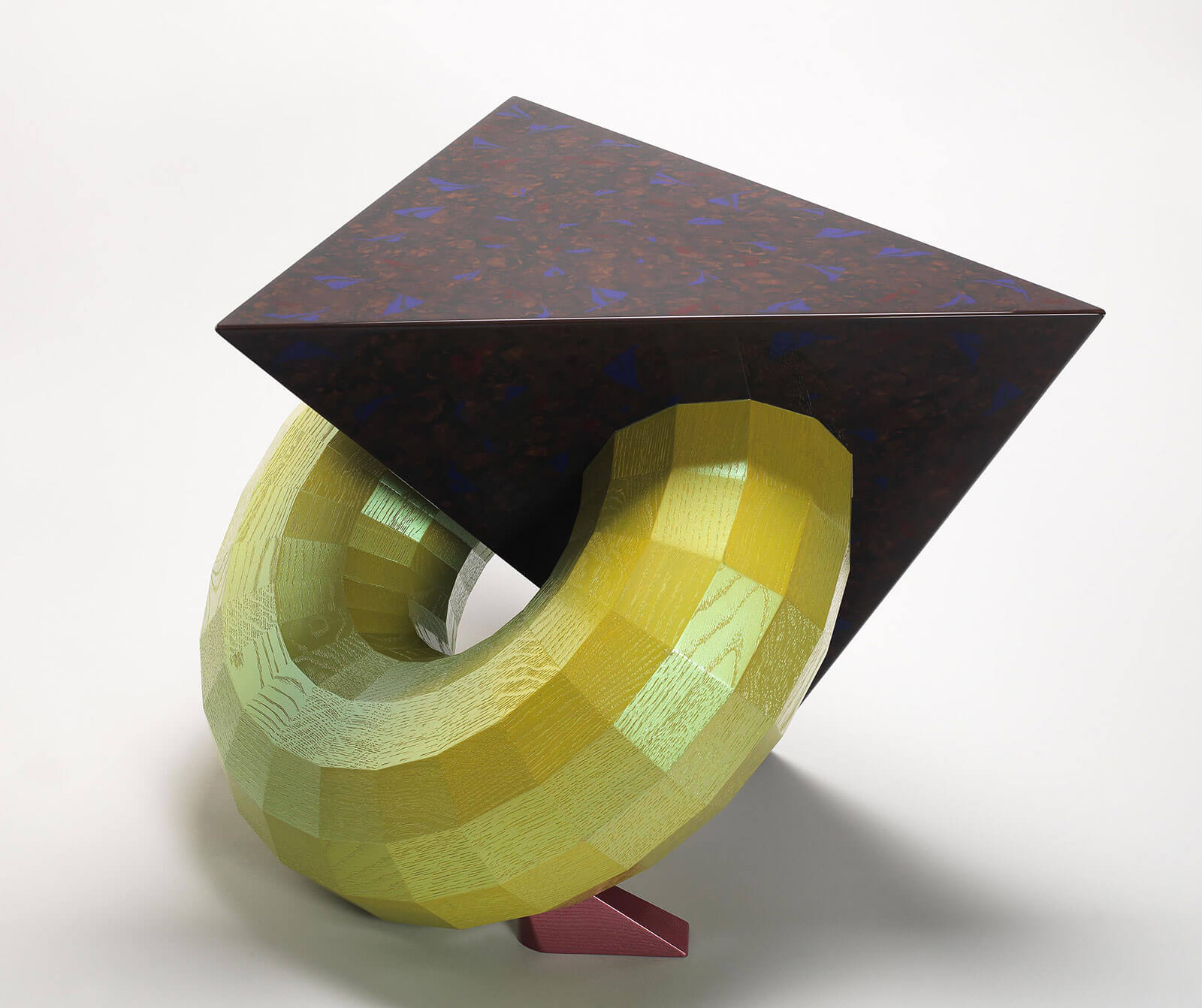

More recently, however, Baier has stepped back from computer technology. To be ahead of the curve is expensive and time-consuming, and “I have got a woodworking workshop and I have woodworkers hands.” However, whenever an idea requires some computer input – a recent ‘Anamorphic’ table, with geometry so complex it required CNCed mortice and tenon joints, and an oval table based on the toroid – a doughnut-shaped geometric form best manipulated on a computer – Baier turns to collaborators.

Fred Baier, ‘Tetrahedron & Toroid’ side table, 2012 (designed 1995)

COURTESY: Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

What drives all his work is his vivid imagination, his love of machines and his fascination with mathematics. Almost all his work is done to commission, for people who, in his words, “want a bit of Fred”. So he starts with the idea in his head, playing about with form before he even considers function. “Then I change the proportions,” Baier says, “so that it can interact with the human form.” At the same time, he is quite clear that he not a fine art sculptor. He explains, “When I am making these forms, which haven’t yet got a furnitureness to them, I am still imagining they are going to be furniture.”

It is these imagined pieces, transformed through intense problem-solving into three-dimensional objects, which are currently dotted through the spaces at Roche Court, for visitors to marvel at.

Installation view

COURTESY: New Art Centre

The New Art Centre – please check the website for opening times/COVID-19 lockdown restrictions.