Giacomo Ravagli: Open Vein

A new exhibition of geometric sculptural lights and minimalist tables sings of the Italian designer’s honed sculptural skills.

Carpenters Workshop Gallery Paris

8th September-3rd December 2022

Giacomo Ravagli, ‘Toro’ wall lamp, 2022

COURTESY: Giacomo Ravagli & Carpenters Workshop Gallery

“FOR A DESIGNER, making a lamp is probably the hardest thing to do,” says Italian designer Giacomo Ravagli, bending over the geometric lighting sculptures unveiled in his first solo show, ‘Open Vein’, at Carpenters Workshop Gallery in Paris. “The challenge is complicated technically and about researching solid volumes to see how they relate to light and its temperature.”

Giacomo Ravagli, ‘Bzzzzzz’ table lamp, 2022

COURTESY: Giacomo Ravagli & Carpenters Workshop Gallery

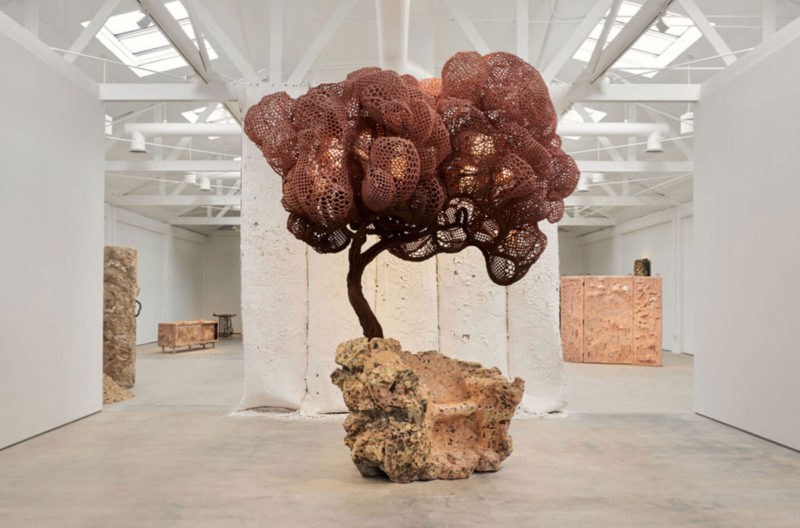

On view are pieces made from stones such as travertine, breccia and basalt that Ravagli carved in Tuscany to accentuate their patterns and achieve bold, anthropomorphic shapes. A table lamp titled ‘Bzzzzzz’ reminds him of a bee; the ‘Headstand’ floor lamp faintly resembles an upside-down face, or an African mask. “It’s like how kids try to find figures in clouds,” Ravagli says.

Giacomo Ravagli, ‘Headstand’ floor lamp, 2022

COURTESY: Giacomo Ravagli & Carpenters Workshop Gallery

Each stone has its particularities. The basalt of ‘Headstand’ is from Mount Etna in Sicily. Black and porous, this igneous rock originated from magma, the molten material that solidified after flowing out of the volcano. “When I work with this stone, I have to protect myself with a mask,” Ravagli explains. “It really feels alive – the smell of the dust is like fire and ashes.”

Giacomo Ravagli, ‘Headstand’ floor lamp, 2022 (detail)

COURTESY: Giacomo Ravagli & Carpenters Workshop Gallery

Ravagli has paired the sculpted bases with translucent shades made from Indian mica – a mineral silicate characterised by shiny flakes. “I visited a monastery in Russia where I saw small-sized windows made out of mica and thought of applying this to my work,” he recalls. Ravagli arranged the mica flakes on a heat press in order to make ultra-thin sheets. The result was random, unpredictable, with scatterings of browns, reds and greens appearing on the surface.

Giacomo Ravagli, ‘Torero’ wall lamp, 2022

COURTESY: Giacomo Ravagli & Carpenters Workshop Gallery

Born in 1981, Ravagli learnt how to carve stone by apprenticing in the workshops of Pietrasanta, a small town that is Italy’s world-renowned sculpture capital. Carrara marble was first excavated here by the Romans; today there are dozens of studios that manufacture works for artists. From the age of 18, Ravagli honed his craft, producing ornaments and decorations as well as outdoor sculptures for the likes of Louise Bourgeois.

Giacomo Ravagli, ‘Stationary points’ table, 2021

COURTESY: Giacomo Ravagli & Carpenters Workshop Gallery

Developing his own artistic language has been something of an odyssey. Whilst living in New York and collaborating with interior designers over a decade ago, Ravagli met Nina Yashar, owner of Nilufar Gallery in Milan, and began making works for her. Some years later, he lived in southeast India, near Chennai, and met skilled craftsmen who would carve black granite to make religious figures of Ganesh and other Hindu gods.

-

Giacomo Ravagli, ‘Tolu Bommalatam’ floor lamp, 2022

COURTESY: Giacomo Ravagli & Carpenters Workshop Gallery

-

Giacomo Ravagli, ‘Vulgata VI’ floor lamp, 2019

COURTESY: Giacomo Ravagli & Carpenters Workshop Gallery

Ravagli set up a workshop there, an experience that marked a creative turning point. “In Italy, I’d been trained like a machine and this very mathematical, scientific approach to sculpture would somehow block and flip me if I wasn’t doing it right,” he recalls. “In India, they work with their eyes. The artisans taught me to trust myself more and not be scared of making mistakes and I taught them to be more precise.”

Giacomo Ravagli, ‘Nose’ table, 2022 (detail)

COURTESY: Giacomo Ravagli & Carpenters Workshop Gallery

Returning to Italy, Ravagli strode out more confidently to make pieces with liberated forms. Unlike many designers, he seldom draws, preferring to envision his ideas and make one-to-one scale plaster models before translating them into stone. “I hate drawing,” he exclaims. “I do drawings only out of necessity.”

Giacomo Ravagli, ‘Meduse’ table, 2022

COURTESY: Giacomo Ravagli & Carpenters Workshop Gallery

Instead, Ravagli imposes a set of rules upon himself as part of his creative process. “I follow my rules, restrictions and mathematical formulas until I find the right shape,” he explains. “It’s very much about the void and the volume, constantly moving around the piece.” Ravagli tends to work outside and has a studio with a transparent roof through which sunlight pours in and the dust dissipates. “You can’t really work inside, it’d be a crazy mess,” he remarks.

Alongside the lamps are consoles and a side table. Exemplifying Ravagli’s prowess is ‘Nose’ – a console with a two-layered top carved from a single piece of stone. “Using two slabs was way too easy,” he quips. “You only realise that it’s one seamless piece when you see it close up.”

Giacomo Ravagli, ‘Nose’ table, 2022

COURTESY: Giacomo Ravagli & Carpenters Workshop Gallery

Hidden away in the gallery’s new extension used for offices and receptions is the dramatic ‘Modular Chandelier’ (2019). Ravagli made it from several sheets of brass arranged at striking angles in the gallery’s workshop in Mitry-Mory, northeast of Paris. “It’s in the different blues of the sea,” says Ravagli, visibly excited. He also notes how the patinated brass interior turns green and turquoise when it catches the light.

The show at Carpenters Workshop Gallery is the culmination of a gradual distillation of ideas reflecting how Ravagli has travelled around over the years. “My way of living, always on the go, doesn’t allow me to be very productive but I’m getting [my feet] more on solid ground now,” he says, smiling. “I’m a one-man studio, doing everything myself.”

Giacomo Ravagli

COURTESY: Giacomo Ravagli & Carpenters Workshop Gallery / PHOTOGRAPH: Teddy Freeman

‘Giacomo Ravagli: Open Vein’ at Carpenters Workshop Gallery Paris.