Max Clendinning: Interior Eulogies

A new exhibition celebrates the avant-garde furniture designer of London’s Swinging Sixties.

Sadie Coles HQ

13th September – 1st October 2022

Max Clendinning, ‘Saturn’ table and ‘Satellite’ chairs, for Race Furniture Ltd.; Ralph Adron, curtain for the artists’ own home, 1966-1967

COURTESY: Sadie Coles HQ, London & © Max Clendinning & Ralph Adron / PHOTOGRAPH: Katie Morrison

THE LATE ARCHITECT, interior and furniture designer and artist, Max Clendinning, and his life partner Ralph Adron – a painter and theatre-set designer with whom he closely collaborated – were key movers and shakers in Swinging Sixties London. They revelled in and popularised a free, expressive approach to domestic interior design widely adopted in the UK in the 1960s and 1970s.

Treating their high-ceilinged homes in North London (first a Georgian house in Canonbury, then a Victorian one in Islington) as giant canvases, they painted ceilings and walls with flamboyant murals and filled rooms with their avant-garde furniture. The couple experimented with a whole raft of emerging, zeitgeist-capturing styles: pop; space-age futurism; Art Deco revivalism; minimalism and surrealism. Advocating eclecticism, they often blended these styles. Their out-there interiors filtered into pop culture since they were regularly used for photoshoots, notably by journalist Janet Street-Porter, at the time Home Editor at hip young women’s magazine Petticoat.

The home of Max Clendinning and Ralph Adron, Islington, London circa 1967. Furniture

and mural designed by Max Clendinning, mural executed by Ralph Adron. Clock designed

and made by Ralph Adron. Clendinning’s grey-painted cabinet now in the collection of the Victoria & Albert Museum, London.

COURTESY: RIBA Collections & © Max Clendinning & Ralph Adron

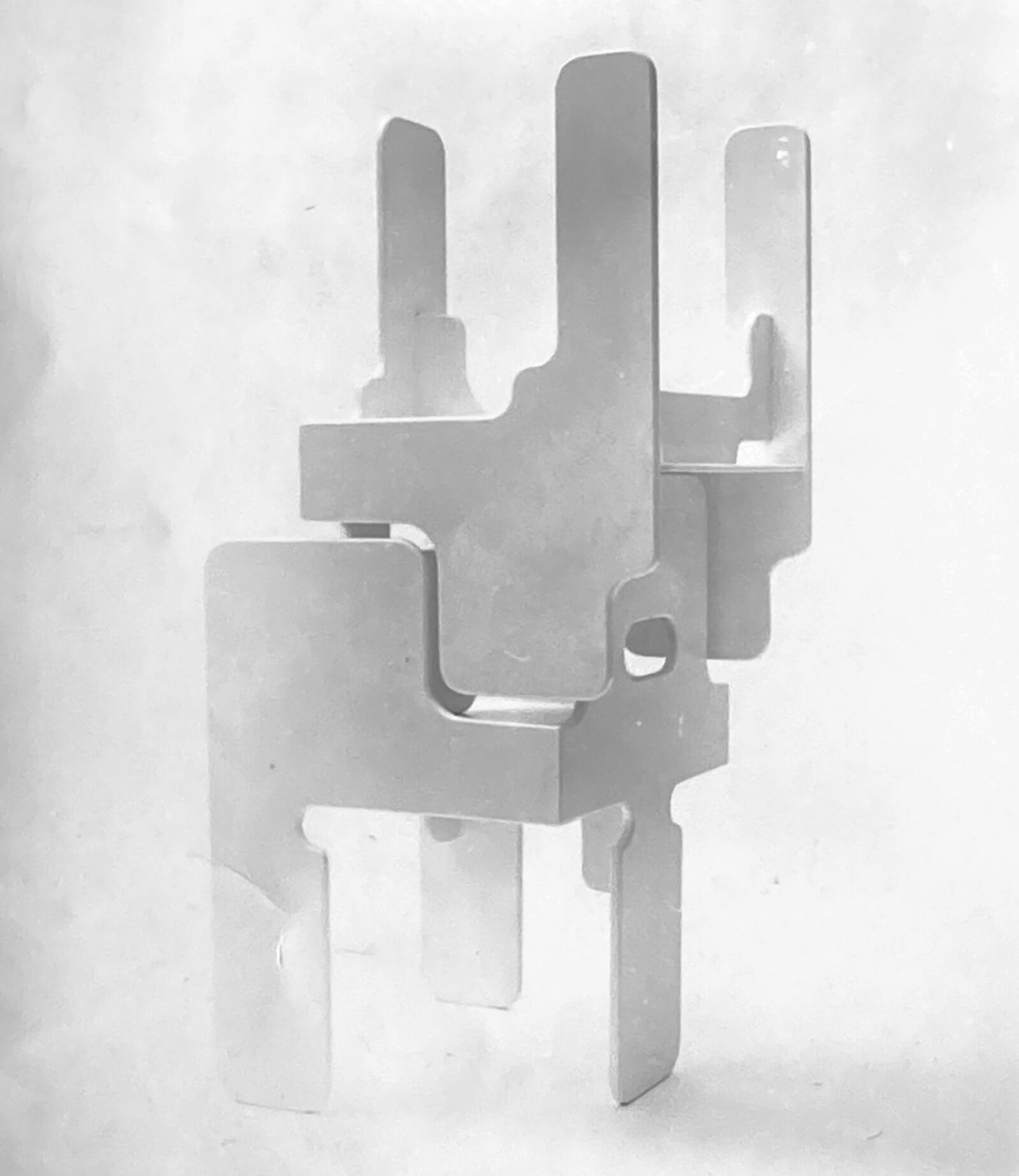

Clendinning, whose family were furniture-makers, also designed ultra-pop furniture, such as chairs for Liberty & Co. Drawn by him on plywood sheets, these designs were cut with a jigsaw by his brother, giving them an artisanal quality. His tables and chairs for Race Furniture (founded by furniture designer Ernest Race), feature ergonomic curves that recall the futuristic, 1960s font, Westminster, designed by Leo Maggs and inspired by the computer-like numerals on bank cheques.

Max Clendinning, ‘Saturn’ table and ‘Satellite’ chairs, for Race Furniture Ltd.; Ralph Adron, curtain for the artists’ own home, 1966-1967

COURTESY: Sadie Coles HQ, London & © Max Clendinning & Ralph Adron / PHOTOGRAPH: Katie Morrison

Now Clendinning and Adron’s bold designs are in the spotlight again, thanks to an exhibition called ‘Max Clendinning: Interior Eulogies’ at London gallery Sadie Coles HQ – an unusual move for a gallery that normally shows art. Adron has lent his support to the show, which includes furniture for Liberty & Co and Race Furniture, a console, sofa and sculptures from their Islington home, pieces from other private collections as well as photographs, illustrations and artworks.

Max Clendinning, ‘Ariel’ chair, for Race Furniture Ltd., 1967

COURTESY: Sadie Coles HQ, London & © Max Clendinning & Ralph Adron / PHOTOGRAPH: Katie Morrison

The exhibition, which overlaps with the London Design Festival, arose following conversations between its curator Simon Andrews, a design expert and long-standing fan of Clendinning, and gallerist Sadie Coles. “We both feel it’s important to celebrate creativity, irrespective of medium and era,” says Andrews, formerly Senior International Specialist for Christie’s. “Sadie invited me to curate a show and I suggested one about Clendinning. He’s an unsung figure, largely overlooked save by the cognoscenti. When I was a student, I discovered the first article about Max and Ralph’s home in Canonbury, published in The Studio Yearbook in 1967. Then, some 20 years ago, I met Max at Christie’s by chance when I was selling a pair of his chairs. The mythology surrounding him is strong but the objects he produced were always scarce.”

Contact print, experimental chairs designed by Max Clendinning for Liberty & Co, London, 1965

COURTESY: © Max Clendinning & Ralph Adron

Born in County Armagh, Northern Ireland, Clendinning trained as a painter before qualifying as an architect in London in 1953. “He played a part in the postwar reconstruction of Britain,” says Andrews. Early projects included designs for the ‘Britain Can Make It’ exhibition at the Victoria & Albert Museum, London in 1946 and the Festival of Britain of 1951. He designed the now Grade II-listed Manchester Oxford Road train station and Crawley Civic Centre in 1964. On establishing his own studio in 1965, he focused on interior and furniture design. Early 1970s projects included an all-grey boutique for Christian Dior and an Art Deco-inspired kitchen with a high-gloss, scarlet ceiling and custom-made units for the East London home of Street-Porter and her then husband, photographer Tim Street-Porter.

The home of Max Clendinning and Ralph Adron, Islington, London circa 1966. Furniture

designed by Max Clendinning

COURTESY: RIBA Collections & © Max Clendinning & Ralph Adron / PHOTOGRAPH: John Donat

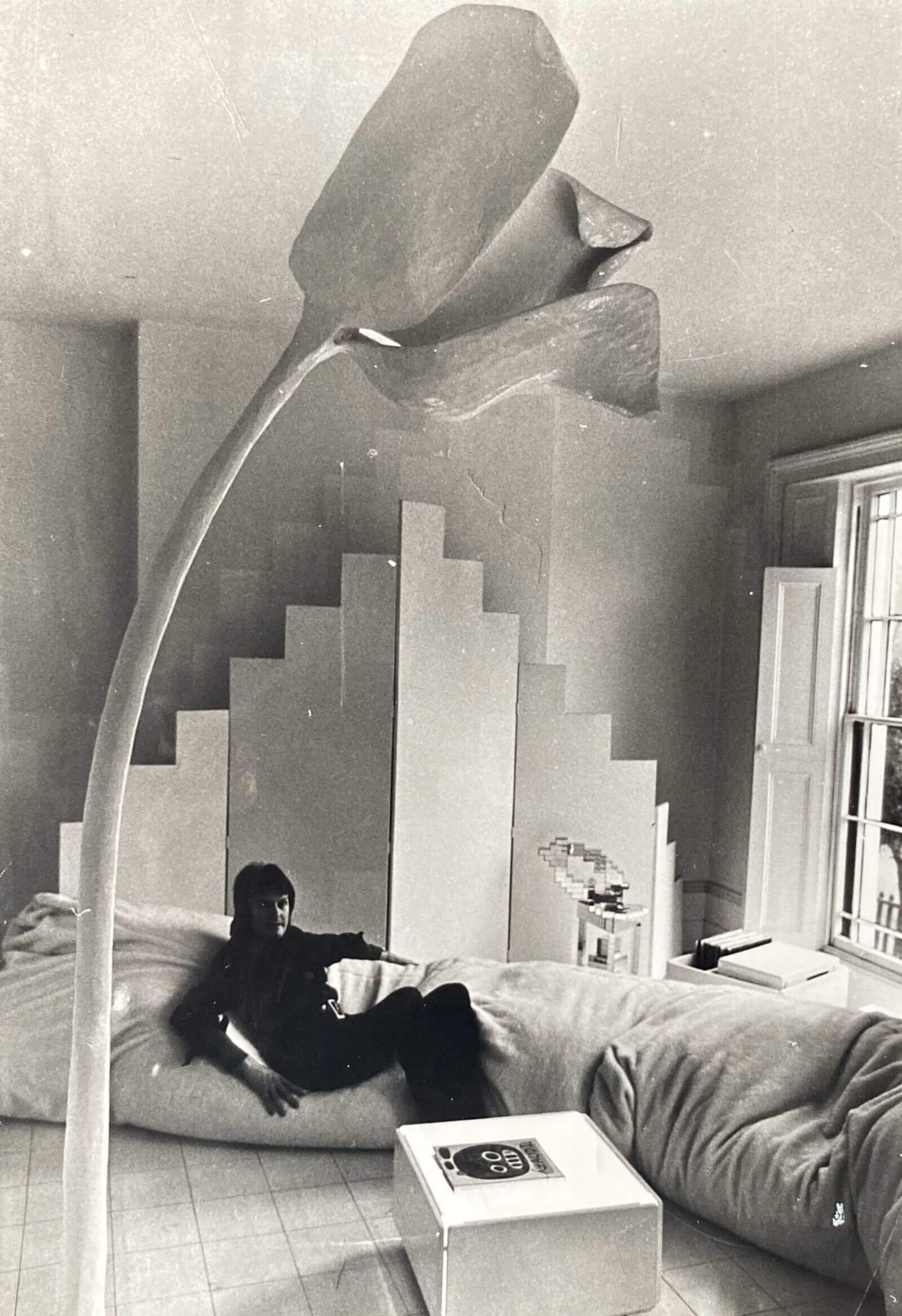

Since Clendinning and Adron co-created their interiors, why were they attributed to Clendinning? “Max was gregarious, front of house, meeting clients,” explains Andrews. Clendinning certainly looks the part in one 1960s photograph in which he strikes a debonair pose on a sofa, part of a family of plastic modular furniture designed for Aerofoam. Adron, meanwhile, was handy and practical; he rustled up many whimsical objects in their homes, including a Brobdingnagian, papier-mâché floor lamp shaped liked a tulip – created for a photoshoot – that towered over a white floor strewn with polar bear-white beanbags in a seemingly all-white room.

Max Clendinning at home, Islington, London, 1966

COURTESY: Ralph Adron collection © Max Clendinning & Ralph Adron

Yet Clendinning and Adron were as interested in subtlety as they were in spectacle, adds Andrews: “There were very subtle shades in this interior. The tulip is a very pale yellow. A Deco-inspired ziggurat on one wall combines pale blue and pink ice cream colours.”

Clendinning and Adron aren’t as well-known today as David Hicks and John Stefanidis, also fêted for their outré, 1970s interiors. Yet arguably their restless experimentation, which embodied two cornerstones of the pop movement – transience and youthfulness – subverted the elitism of British interior design previously epitomised by Syrie Maugham and Colefax and Fowler. Clendinning’s legacy might have been stronger, believes Andrews, had he stuck to one style. But he sees the exhibition as an opportunity to reappraise it. “The show will shine a light on his work and encourage a new generation to discover it.”

Max Clendinning, two ‘Satellite’ chairs, for Race Furniture Ltd., 1966.

COURTESY: Sadie Coles HQ, London & © Max Clendinning & Ralph Adron / PHOTOGRAPH: Katie Morrison

‘Max Clendinning: Interior Eulogies’ (curated by Simon Andrews) is at Sadie Cole HQ, 8 Bury Street, London SW1Y 6AB.