Memphis – Plastic Field

A vibrant collection of over 160 iconic works from Sottsass’s Memphis Group, exhibited against the backdrop of a former 19th century prison.

Musée des Arts Décoratifs et du Design (MADD), Bordeaux, France

21st June 2019 – 5th January 2020

THE MEMPHIS EXHIBITION at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs et du Design (MADD) coincides with Bordeaux’s ‘Liberté’ season, which sees freedom-themed cultural events held throughout the city. It takes place 35 years since the museum’s then director, Jacqueline Du Pasquier, whose daughter Nathalie Du Pasquier was a member of Memphis, organised the first Memphis show outside Italy.

Memphis was founded in 1981 by Sottsass. Its name was coined from a 1960s Bob Dylan song, ‘Stuck Inside of Mobile with the Memphis Blues Again’, that Sottsass and his coterie of young designers and architects listened to during a meeting.

Masanori Umede, ‘Tawaraya’, 1981

COURTESY: © Madd-bordeaux / PHOTOGRAPH: Laurent Gueneau

The first Memphis exhibition at the gallery Arc ’74 in Milan broke the Bauhaus form-follows-function theory in favour of experimenting with colour, emotion, sensuality and forms. Disrupting the codes of good taste, materials were daringly and playfully juxtaposed. And, thanks to Ernesto Gismondi, founder of Artemide, the collection was distributed worldwide. Against the backdrop of Italy’s 1970s financial crisis and the rise of the Red Brigades – a terrorist organisation responsible for robberies, kidnappings and murders – Memphis breathed inventiveness and optimism. Karl Lagerfeld described seeing the first collection as “love at first sight” and furnished his Monte Carlo apartment with more than 150 Memphis pieces. His Memphis collection was auctioned by Sotheby’s in Monaco in 1991.

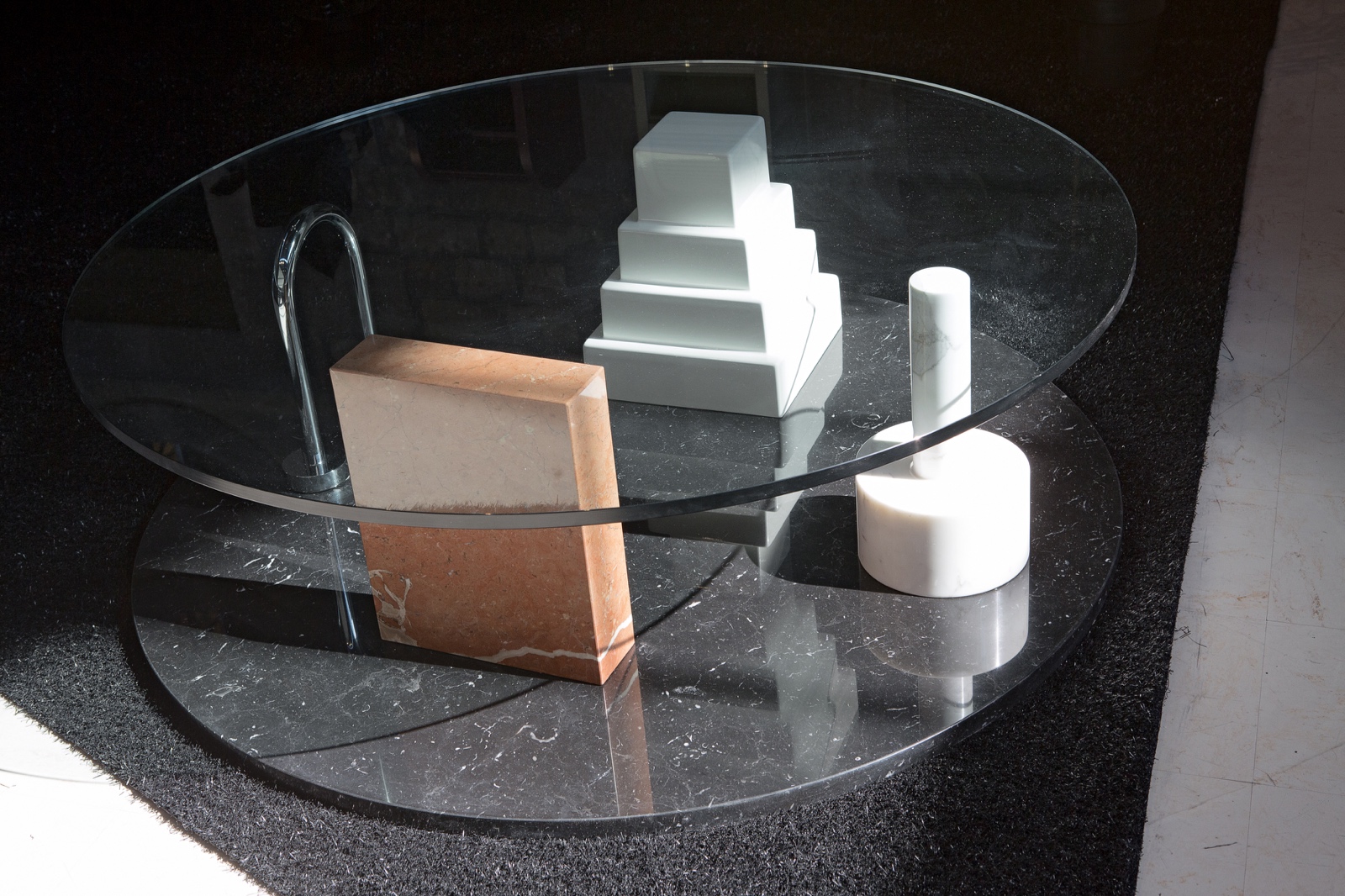

Ettore Sottsass, ‘Park’, 1983

COURTESY: © Madd-bordeaux / PHOTOGRAPH: Laurent Gueneau

‘Memphis – Plastic Field’ was first presented by Fondazione Berengo at Palazzo Franchetti during last year’s Venice Architecture Biennale. Including works from the inception of Memphis in 1981 through to its last collection in 1987, it seduced MADD’s director, Constance Rubini, who brought it to Bordeaux. Co-curated with Jean Blanchaert, curator of the Venice show, this new iteration exchanges the sumptuous palazzo for the stark interior of a former 19th century prison. The prison buildings are part of MADD, and lie across a cobbled courtyard from the mansion that houses the decorative arts museum.

Installation view, ‘Memphis Plastic-Field’

COURTESY: © Madd-bordeaux / PHOTOGRAPH: Laurent Gueneau

The brightly coloured Memphis pieces are offset by a jungle-like scenography of black astro turf and plastic plants. Created by IB Studio – Isabella Invernizzi and Beatrice Bonzanigo – the angular scenography is based on Ettore Sottsass’s ‘Carlton’ (1981), a bookcase/room divider greeting visitors at the entrance.

“The idea is that in the ruins of a prison, overgrown by a jungle, we discover a civilisation that has disappeared, which is Memphis,” Rubini says. “Memphis embodies freedom and it’s important to show the movement’s strength, radicality and singularity.”

Alessandro Mendini, ‘Cipriani’, 1981

COURTESY: © Madd-bordeaux / PHOTOGRAPH: Laurent Gueneau

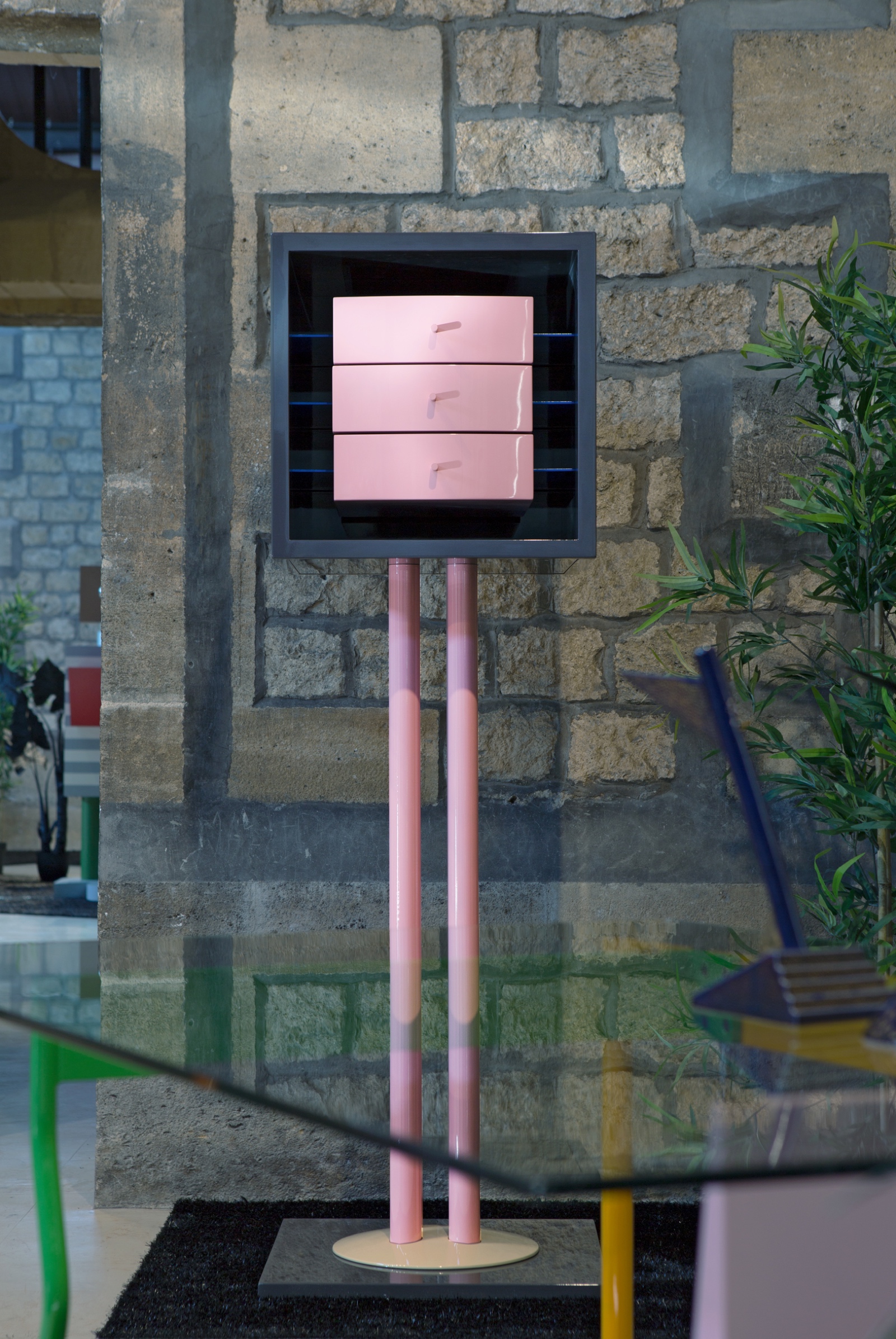

In the first room is ‘Tawaraya’ (1981), the black-and-white striped boxing ring with bright poles and lights by Masanori Umeda. While a photograph of the Memphis designers lying in the ring has been widely published, it’s rare to see the iconic piece exhibited. Umeda was one of three Japanese designers, along with Shiro Kuramata and the architect Arata Isozaki, who participated in the Memphis adventure. Among Kuramata’s pieces is the ‘Nikko’ (1982) drawer cabinet in metal and lacquered wood. An elegant distortion of a classical cabinet, its pale pink drawers are encased in a black cube on two elongated poles standing in a yellow circle in a black square.

Shiro Kuramata, ‘Nikko’, 1982

COURTESY: © Madd-bordeaux / PHOTOGRAPH: Laurent Gueneau

Indeed, Memphis was international in scope. Sottsass united Italian designers such as Andrea Branzi, Aldo Cibic, Michele De Lucchi, Alessandro Mendini and Marco Zanuso Jr., American designers Michael Graves and Peter Shire, British designer George Sowden and French designer Martine Bedin. Among the strong pieces on view are Graves’s ‘Plaza’ (1981), a snazzy, turquoise dressing table with a gold-and-white mirror, and Shire’s ‘Bel Air’ (1982), a witty, asymmetrical armchair.

Michael Graves, ‘Plaza’, 1981

COURTESY: © Madd-bordeaux / PHOTOGRAPH: Laurent Gueneau

Sottsass’s coffee tables ‘Park’ and ‘Park Lane’, both from 1983, reveal his passion for mixing materials. The first has geometrical, steel and marble forms under a glass top and arranged on a marble disc. “With its mix of architectural forms, scales and materials, it’s as if there’s a city underneath the glass,” says Rubini. The second has a black marble base supported by glittery green fibreglass legs. “Who, apart from Sottsass, would have thought of combining those two materials?” Rubini asks.

Marco Zanini, ‘Roma’, 1986 (armchair); Ettore Sottsass, ‘Park Lane’, 1983 (table); Andrea Branzi, ‘Gritti’, 1981 (bookcase)

COURTESY: © Madd-bordeaux / PHOTOGRAPH: Laurent Gueneau

Memphis’s fun-like spirit is encapsulated in Bedin’s ‘Super’ (1981), a small blue wagon on wheels with five flashing light bulbs, and in objects such as Sottsass’s ‘Tahiti’ (1981) lamp. The most beautiful display in one of the cells is the collection of glass vases and bowls that Sottsass created with Marco Zanini in 1982, 1983 and 1986. Each piece is fashioned from gluing or holding together variously coloured elements.

Martine Bedin, ‘Super’, 1981

COURTESY: © Madd-bordeaux / PHOTOGRAPH: Laurent Gueneau

Ettore Sottsass and Marco Zanini, glass collection, 1982, 1983, 1986

COURTESY: © Madd-bordeaux / PHOTOGRAPH: Laurent Gueneau

While the exhibition captures Memphis’s unique exuberance, what’s lacking is the historical context of why it occurred, and why it disbanded. As Rubini says, “The designers never wrote a manifesto. There was a lightness of renewal in the collections and, as the designers didn’t want Memphis to become institutionalised, it couldn’t last longer than it did.” As Sottsass gradually distanced himself from the movement, the other designers pursued their own paths. “What’s remarkable is that some of the pieces are still produced today,” Rubini enthuses.