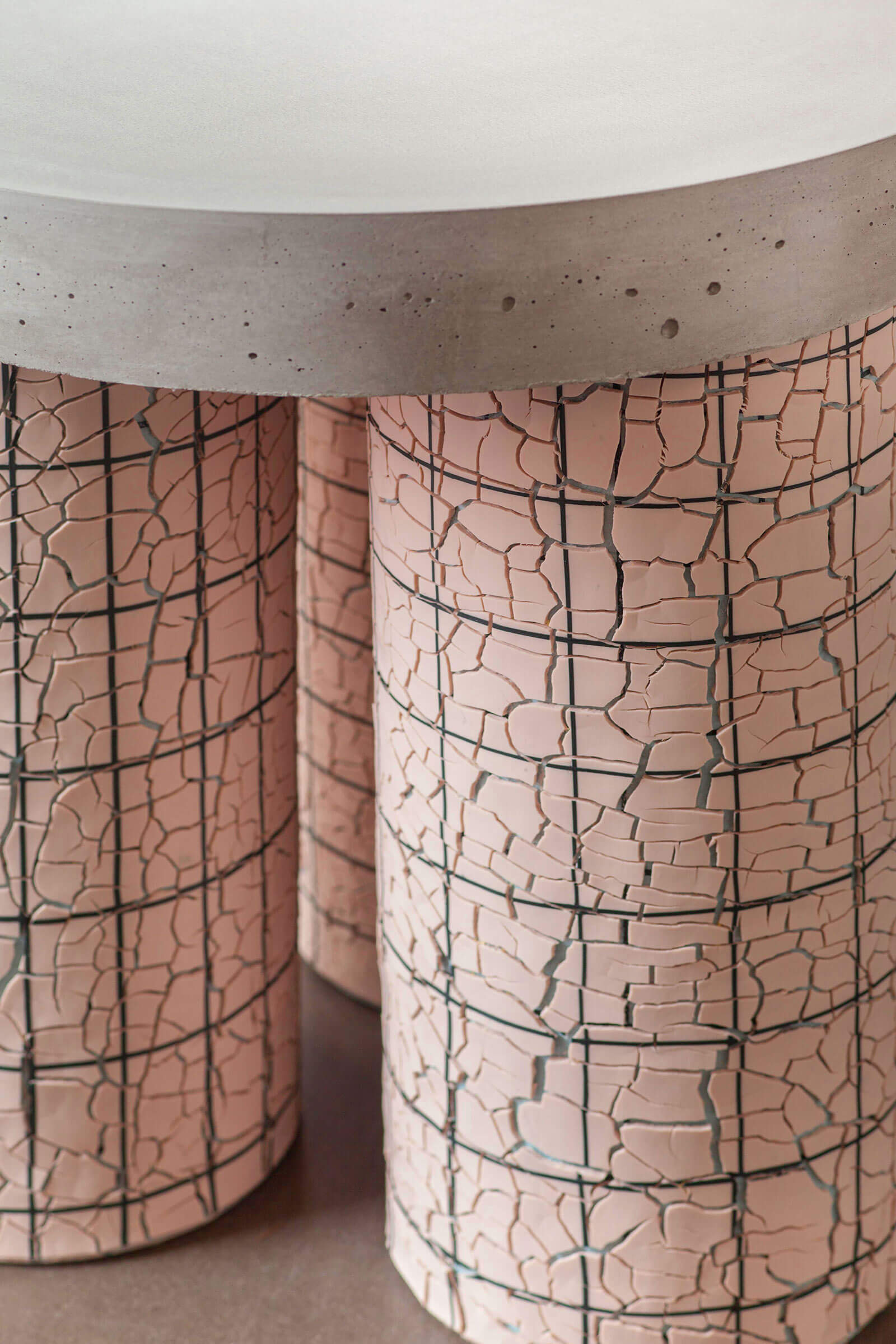

‘GRID Pink Table’, 2021

Irina Razumovskaya

Irina Razumovskaya, ‘GRID Pink Table’, 2021

COURTESY: Irina Razumovskaya & Aybar Gallery

ANCHORED IN BY a recessed grid of thin stripes, a ‘crackled’ ceramic surface forms the exterior of three cylindrical bases that prop up a concrete tabletop. The visceral contrast of crystalline geometric forms and a rough, richly textured skin alludes to the jarring interplay of entropic material decay and the lasting imprint of urban road systems. Russian ceramicist Irina Razumovskaya has masterfully employed age-old techniques, such as the controlled chaos of clay shrinkage, to achieve this effect.

“I was born in Leningrad, a city and country that no longer exists,” she explains. “For me, witnessing the grand Constructivist and Soviet-era building around me crumble and fall apart, due to harsh climate and the poor quality of cement, is very poetic.” Razumovskaya’s education brought her in close contact with ancient architectural forms. For her, the built environment is symbolic of not only specific cultures but also periods in time. The artist’s interest in dilapidation is closely linked with the complexities of context and identity.

Explored in 20 iterative pastel-hued works grouped in series called ‘GRID’, ‘ARCHI’ and ‘CONCRETE LANDSCAPE’, her latest work reflects Razumovskaya’s own aesthetic heritage and the classically-trained artist’s first foray into functional object-making. Developed for Miami Beach-based Aybar Gallery, the architectonic tables, lamps and sculptures all riff on the same underlying conceptual juxtaposition.

“It’s a metaphor for how the hopes and beliefs of a whole nation can vanish; how the truths, mistakes and ambitions of those involved are ultimately just temporary,” she describes. “On the one hand, these objects exist in this moment but, on the other, appear to be disappearing or melting away. Clay is perhaps the most permanent material we’ve been able to harness as human beings, but in this case, it freeze-frames a more unstable and transitory moment. The material can emulate the passage of time. Twenty-four hours in a kiln can mirror centuries.”

For Razumovskaya, working with the material represents a tacit understanding of its craft, an implicit set of skills she began acquiring early on. The artist is careful to allow the properties of the material to embody its own narrative, image, and mood. “There is a reason that it has been prized since the earliest days of human civilization,” the artist reflects. “Clay is both close to nature and the body. It can surprise you and guide you, which is why I have spent so much of my career trying to push its boundaries and experiment with novel forms and effects.”

-

Irina Razumovskaya, ‘GRID Pink Table’, 2021

COURTESY: Irina Razumovskaya & Aybar Gallery

-

Irina Razumovskaya, ‘GRID Pink Table’, 2021 (detail)

COURTESY: Irina Razumovskaya & Aybar Gallery

-

Irina Razumovskaya, ‘GRID Pink Table’, 2021 (detail)

COURTESY: Irina Razumovskaya & Aybar Gallery