Joseph Walsh: designer maker

Glenn Adamson explores the boundless creative energies of Joseph Walsh, whose passion for making has brought the world to his doorstep.

Joseph Walsh Studio Magnus Modus

A peek inside the Irish designer’s rural studio in County Cork

THE DESIGNER’S MOST important tool, they say, is a pencil. This is certainly true of Joseph Walsh. Visit his studio, nestled in the countryside of County Cork, Ireland, and you will invariably see him drawing. In what seems a single continuous gesture, transiting gracefully from one project to the next, he puts pencil to paper – sketching towards a new idea – then directly to the surface of his wooden furniture and sculpture, defining and redefining its contours. Once finished, after weeks or months of highly skilled crafting, these works still have something of the pencil in them; they are like lines uncoiled and sprung into the world.

Joseph Walsh, ‘Enignum Shelf’, 2018

COURTESY: Joseph Walsh Studio / PHOTOGRAPH: Andrew Bradley

Walsh cuts an unusual figure in the design landscape, and not only for the quality and quantity of his output. He is entirely self-taught – apart from a few skills he picked up from his grandfather as a boy – and operates largely outside of the gallery system that drives much of contemporary design, principally working through private commissions.

Joseph Walsh

COURTESY: Joseph Walsh Studio / PHOTOGRAPH: Andrew Bradley

He is also an outlier in geographical terms. While Ireland has had an active design scene since the 1960s, its energies are concentrated either in heritage firms (like Beleek Pottery, J. Hill’s Standard, and Waterford Crystal), or in small craft studios. Though Walsh is far off the beaten track – his shop is situated on his family’s farm in Riverstick, where he grew up – he maintains a large workforce of about twenty, including skilled artisans from Japan and France alongside local talent. This cosmopolitan mix seems to suit him well; for a country lad, he spends a good deal of time on aeroplanes.

Joseph Walsh Studio, 2019

COURTESY: Joseph Walsh Studio / PHOTOGRAPH: Andrew Bradley

FOR MANY YEARS the heart and soul of Walsh’s work was bent olive ash, a locally available and sustainable timber. When he was first starting out in the 1990s, he was inspired by the work of British furniture maker John Makepeace to try steam bending, which makes wood temporarily malleable, allowing it to be shaped in a mould. This tried-and-true technique was for him a radical breakthrough. Animated from the first with a desire to push his skills and materials as far as they could go, he began developing a repertoire of curved, laminated forms, reminiscent of the turbulent whiplashes of Art Nouveau. As commissions began coming his way, he approached each one as a challenge, working to achieve greater scale, steeper curves and higher complexity. And although wood has remained his principle medium, over time he has added other materials to his vocabulary: transparent resin, figured marble, custom upholstery, black lacquer. By now, he and his team have achieved such mastery that their technique melts into the background, in favour of a sensation of pure movement.

Joseph Walsh, ‘Enignum Free Form Seat with Eximon Side Table’, 2018

COURTESY: Joseph Walsh Studio / PHOTOGRAPH: Andrew Bradley

Though Walsh was already getting attention for his work in 2007 – when he was all of twenty years old – it was his ‘Enignum’ series, launched in 2010, that first brought him international acclaim. The title is a portmanteau of “enigma” and “lignum” (Latin for wood), which is fitting, because the pieces have a seductive air of impossibility about them. So taut that they almost visibly quiver, they seem to store in them the kinetic energy imparted by the bending process: a wall shelf that arches sideways, like an arrow in a bow; chairs with the stance of gazelles poised to leap; dining tables with broad tops drifting above asymmetrical nests of curling, free-form ribbons. In the most breathtaking passages of the ‘Enignum’ pieces, the sweeping lines part company with one another, separating into two or three echoing curves, then converging again like a resolving musical chord.

Joseph Walsh, ‘Enignum Dining Table and Enignum II Chair’, 2010

COURTESY: Joseph Walsh Studio/ PHOTOGRAPH: Andrew Bradley

The masterpiece of the ‘Enignum’ series is a bed that Walsh made in 2015 for the View Room at Chatsworth House, the estate of the Duke and Duchess of Devonshire. Located high up in the stately home’s mazy architecture, this bedchamber has a commanding prospect over the surrounding property. Though intimate in plan, the room has a high, vaulting ceiling. Walsh had already made one canopy bed for Chatsworth – itself a marvellous conception, with a drape of translucent organza over its dramatic upswept forms – and now he took full advantage of the View Room’s unorthodox dimensions. The bed’s superstructure corkscrews upwards fully six metres into the air, like a flash-frozen whorl of smoke.

Joseph Walsh, ‘Enignum Bed’, 2015

COURTESY: Joseph Walsh Studio / PHOTOGRAPH: Andrew Bradley

While still a functional piece of furniture – one imagines that its best vantage might be from the mattress, where one can gaze upwards into its twisting forms – the View Bed has a strong sculptural implication, as so much of its form is released into pure abstraction. This dynamic was even more explicit in ‘Magnus Celestii’, Walsh’s first large-scale installation, realised in 2014 for Roche Court, a museum in Wiltshire, England. It travels upwards from a taproot set into the floor, into a horizontal desk. Then it keeps going – and going – enclosing the entire space in a unified spiralling composition, finally arriving in a wall shelf. It’s as if furniture has sprung free of its utilitarian commitments, gone on a wander, and finally come home to rest.

Joseph Walsh, ‘Magnus Celestii’, 2014

COURTESY: Joseph Walsh Studio / PHOTOGRAPH: James Harris

PUBLIC ART LOOKS set to be a whole new arena for Walsh’s considerable energies. Last year he completed another monumental sculpture, entitled ‘Magnus V’, for the commercial property fund IPUT. This is part of an increasingly outward-facing aspect of Walsh’s career, manifested most clearly in a series of events entitled “Making In,” which he has been hosting at his studio. The first of these one-day conferences was held in 2017. I myself became involved as a co-convenor in 2018, where ‘Magnus V’ was unveiled. A third event, entitled “Making In Public,” will be held this year on the 14th of September. The symposia have allowed Walsh to invert his customary direction of travel; instead of going out to meet the designers of the world, he brings them home to Riverstick.

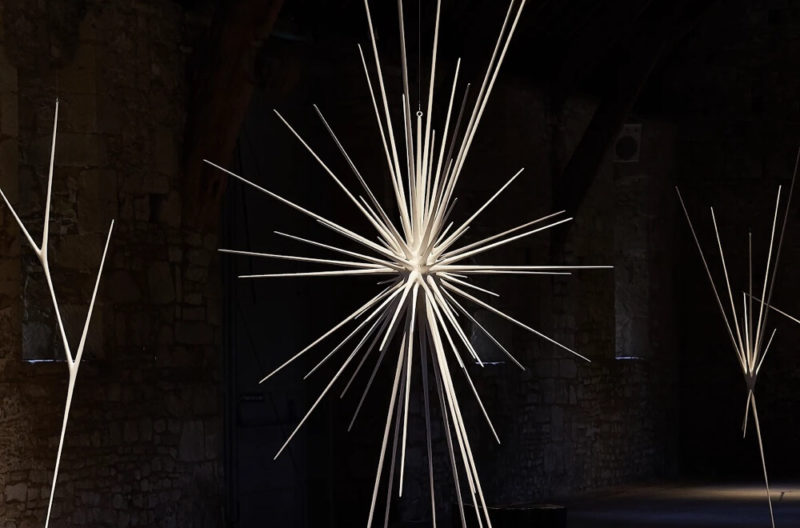

Joseph Walsh, ‘Magnus Modus’

COURTESY: Joseph Walsh Studio / PHOTOGRAPH: Andrew Bradley

“The pieces have a seductive air of impossibility about them …”

Joseph Walsh, ‘Magnus V’

COURTESY: Joseph Walsh Studio / PHOTOGRAPH: Andrew Bradley

” …they seem to store in them the kinetic energy imparted by the bending process”

One of the most charming – and intellectually provocative – aspects of the “Making In” conferences is the mutual encounter they provide between local Irish makers and international contemporary designers. In 2017, the scene was stolen clean away by Joe Hogan, a plainspoken and traditionally skilled basketmaker who lives at the edge of Loch Na Fooey, County Galway. Last year, potter Sara Flynn memorably described the focus and stillness of her tiny Belfast studio, and the necessity of this quality of compression for her subtle, undulating vessels.

Alongside these distinctive Irish voices, the conferences have hosted design superstars from all over, among them Humberto Campana from Brazil, John Makepeace and Gareth Neal from the UK, and this year, Pietro Seminelli, an Italian maestro of fabric design based in Paris. The 2019 edition, which focuses particularly on public engagement, will also include presentations by architects Charles Renfro, Yvonne Farrell and Shelley MacNamara (of Grafton Architects). And Walsh has also consistently made room for Japanese artisans, like the oke (wooden pail) maker Nakagawa Shuji, and luxury craft firms, among them Jarosinski & Vaugoin, the Viennese metalsmiths.

Participants of ‘Making In 2018’

COURTESY: Joseph Walsh Studio

MEANWHILE, WALSH CONTINUES to expand the parameters of his own work. While he continues the long-running ‘Enignum’ series, he has also created other idioms, including ‘Erosion’, which features massive, carved stack-laminations, evocative of geological formations; ‘Lillium’, which tends in the opposite direction, lacy, light, and complex; and ‘Lumenoria’, which emphasises crystal-clear cast resin, used to make table tops or cabinet façades. This last series is particularly demanding for Walsh and his team. It requires a totally different skill set – more chemistry than carpentry – and admits no margin for error. The results are ravishing, though, with rippling optical effects that are very much in keeping with his vocabulary. As ever in his work, that which is solid seems like it could well melt into air.

Joseph Walsh, ‘Lumenoria Dining Table and Dommus Chairs’, 2018

COURTESY: Joseph Walsh Studio / PHOTOGRAPH: Andrew Bradley

What next for Walsh? Already he has established himself as a leading participant in the contemporary furniture dialogue, responding both to elder statesmen like Makepeace and the late Wendell Castle, and to his own generational peers, such as the Dutch digital genius Joris Laarman. While he operates in this space with supreme confidence and originality, I myself wonder whether it is likely to contain him. As we have worked toward the latest iteration of “Making In,” with its explicit emphasis on public engagement, it’s been interesting to see Walsh’s restless mind turning to still larger scales – beyond the seven metres of ‘Magnus V’ to the field of architecture, and even to the urban fabric itself.

Even the most amazing piece of furniture reaches a comparatively small audience: of the few who are able to afford it, and those onlookers who happen to be invested in the discipline as a research field. Already Walsh has given this tight community a great deal, and with his public sculptures, has already begun to step outside of it. Will he now turn his attention to more macroscopic design problems? I wouldn’t be surprised. After all, mathematically speaking, a line – which is the basic unit of Walsh’s creativity – can go on forever. Have pencil. Will travel.

Joseph Walsh, ‘Enignum Canopy Bed’, 2010

COURTESY: Joseph Walsh Studio / PHOTOGRAPH: Andrew Bradley

Joseph Walsh Studio – designer maker based in Cork, Ireland.

Glenn Adamson will be the moderator of ‘Making In: Public’, Saturday 14th September 2019, the third edition of the ‘Making In’ symposium hosted by Joseph Walsh.