Atang Tshikare

As the South African artist brings his masterful storytelling to a global audience, Brecht Wright Gander discovers more about his rich creative process.

Atang Tshikare

COURTESY: Atang Tshikare / PHOTOGRAPH: Kope Figgins

ATANG TSHIKARE GREW up in Thaba ‘Nchu (‘Black Mountain’), one of several so-called “homeland” states that retained independence from the apartheid South African government, even while being enclosed within its broader territory. He was fourteen when the nation was integrated in 1994 – with the election of Nelson Mandela – and his life has been marked by expanding boundaries. Born in a small state existing within a larger, fiercely demarcated state, he has now arrived as an international figure in art and design, currently collaborating on projects across three continents. Tshikare launched his company Zabalazaa Design in 2010, collaborating with local artists and working on commissions with brands such as Adidas Originals, Puma, BMW and MTV Base. He began exhibiting limited-edition sculptural furniture and functional art, in a variety of forms and materials, with Southern Guild in 2012.

Atang Tshikare, ‘Peo e Atang’, 2020

COURTESY: Atang Tshikare / PHOTOGRAPH: Anke Loots

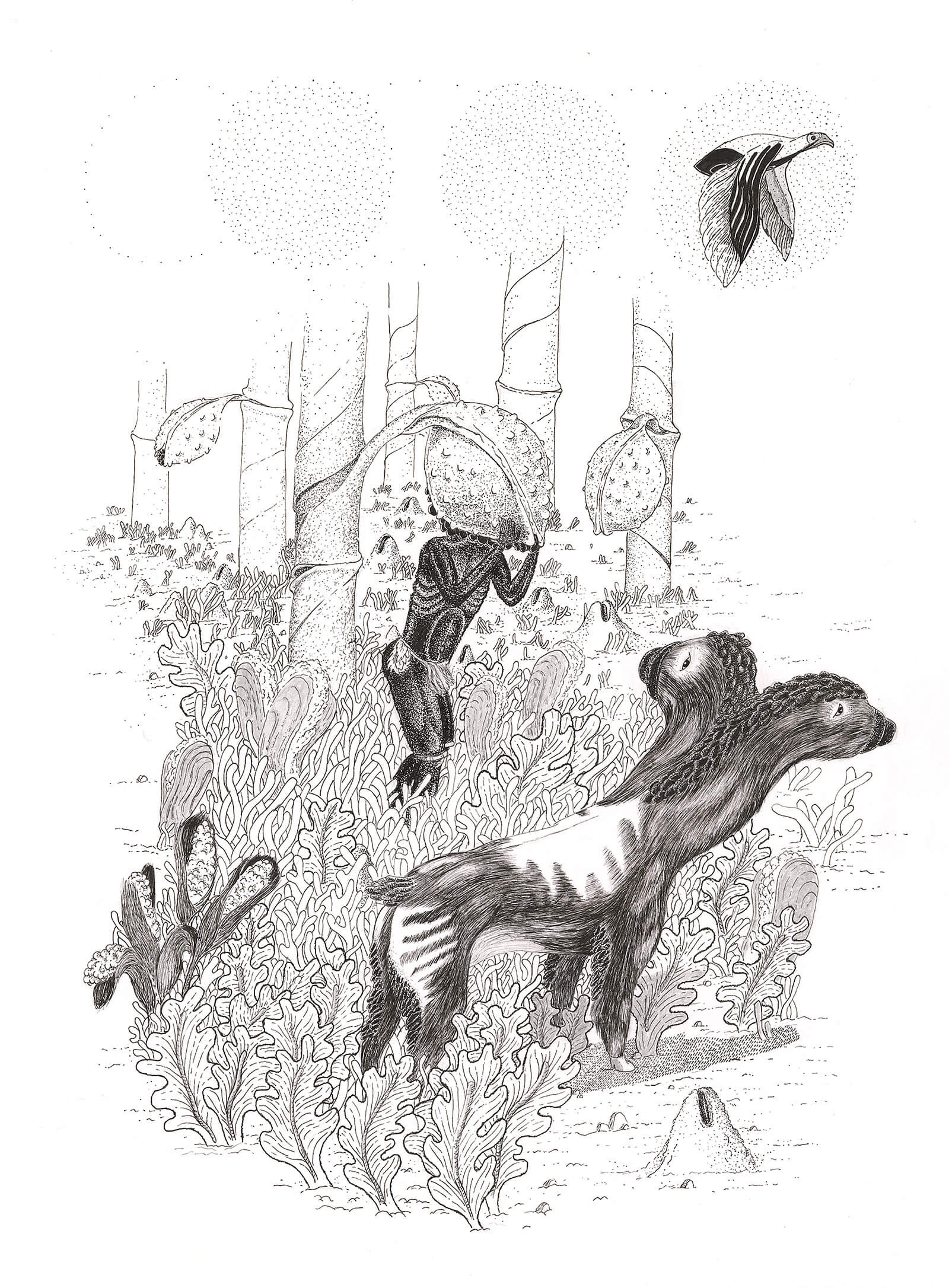

Tshikare’s recent, independently launched solo show, ‘Peo e Atang’, is addressed to his newborn son, Peo. For it, he bound sculpture, music, animation and drawings together into a metastructure he calls a “physical narrative”. The presentation delivers an expansive vision centred on graphical, zoomorphic forms that emerge from fables of Peo’s misadventures. These stories, which the artist began developing even before his son’s birth, reflect the anxieties of a father who knows the world his son will discover is not the world he would give him.

Atang Tshikare, ‘Tau-Tau’, 2020

COURTESY: Atang Tshikare / PHOTOGRAPH: Anke Loots

But Tshikare’s love is supported by his talents, which allow him to render a world of his own description, one which, even in its darker fables, pulses with aesthetic beauty. In addition to ‘Peo e Atang’, which is ongoing, Tshikare is currently included in ‘Before Yesterday We Could Fly: An Afrofuturist Period Room’ at the Metropolitan Museum in New York. He will be unveiling a collaboration with Dior at Design Miami/ in late November.

Atang Tshikare, ‘Botlhale’, 2019

COURTESY: Atang Tshikare / PHOTOGRAPH: Anke Loots

Brecht Wright Gander (BWG): Let me first say that I find ‘Peo E Atang’ deeply moving. It’s a habitable vision, a multimedia project that braids film, drawing, sound, sculpture, design and text into a love-offering for your son. Can you describe how the project developed? Did you envision it comprehensively from the outset, or did one beginning lead to another?

Atang Tshikare, ‘Nageng’, 2020

COURTESY: Atang Tshikare / PHOTOGRAPH: Anke Loots

Atang Tshikare (AT): The project began with a story I wrote in 2006. In 2020, when my son was born I picked it up again and added to it until I felt it had strong characters that could become sculptures. As I planned the sculptures I realised they needed an environment to elaborate where they were based, and so I began to do the drawings alongside the sculptures. This went well and began to feel like an animation movie, so I decided it needed music – this is where I am with the process at the moment. Next year, the first part of the written trilogy should be out and then it will be followed by the music. Hopefully, each year, the sculptures, books, drawings and music will be presented to the world from a different city or continent.

Atang Tshikare, ‘Maru 1’, 2021

COURTESY: Atang Tshikare / PHOTOGRAPH: Anke Loots

BWG: So writing was the generative seed that led to the sculptures, that led to the drawings, that led to animations, that led finally to music. It’s a very unusual development process and it’s especially interesting to me that you began with words. In the west, it’s a pedagogical given that drawing is the first step in visual artwork. Not only that, but your father was an illustrator and you yourself are such a fluent draughtsman. Can you talk to me about the significance of starting with stories rather than images? I’m also curious about music as the apotheosis of your process. So many artists whose work is confined to a single discipline look to music with an envious eye – it is, in some ways, the most immediately transformative medium. Why is it that you find yourself with music at the end?

Atang Tshikare, ‘Diyamaleng’, 2019

COURTESY: Atang Tshikare

Atang Tshikare: As a human, you emit words before you hear them and this is the energy transformation that my work takes – from one manifestation to the next. It is especially so when processing a bigger idea like a solo show. It begins with a single visual, followed by a conversation that I have with myself. The words are then written as an artwork, that plays out as a narrative, that takes on various forms. The drawings and maquettes follow after, sporadically filling in visual gaps as I recite the fable. It’s like planning for a film.

Atang Tshikare, ‘Kgotlhano’, 2019

COURTESY: Atang Tshikare

Once in a while I collect records and play at home, or at small events. When I was younger I played classical piano, keyboards and clarinet. Hence now I make a playlist for my workday and create within a theatrical mood. So, for me, music is a reflection of the created pieces. Once the artwork is created, it tells me what it sounds like.

Atang Tshikare, ‘Sebatana’, 2019

COURTESY: Atang Tshikare / PHOTOGRAPH: Anke Loots

Some of the sound effects (rubbing, grinding, knocking) I get from movements of the materials as I work with/on them. Other sounds I find in nature (wood tearing, stone falling, water gushing), where some of the materials are originally found. Each element has a specific sound wave it emits, which in a way is its narrative, So only when I’ve experienced these various narratives of sound do I consider my artwork concluded. It is all a cinematic experience in 4D.

BWG: Moving from process to the much-abused word, inspiration, family has long been a beginning place for you. For instance, ‘Oa Mpona’, your show in 2017, may in some ways be the template from which ‘Peo E Atang’ emerged. Is that fair to say? It too, uses fables, illustration and sculpture to create a world. It too, has epic scope and reach and is a multi-year project that synthesises your real family and myths of your own authorship. It occurs to me that there is something especially interesting about the way your fables function as histories for new objects. It is as though you are not just innovating form, but, paradoxically, innovating a past, grounding your work in a tradition that never existed. Or that existed partially: your father was an illustrator and your grandmother was a weaver – those are real traditions that you are re-contextualising. How do you see your lived past and the past of your fables in relation to each other?

Atang Tshikare, ‘Kgobokano’, 2021

COURTESY: Atang Tshikare / PHOTOGRAPH: Anke Loots

Atang Tshikare: To answer your first question, I’d say, yes, family is a form of connection I associate well with. Hence all my works are part of one bigger story. The crochet/weaving my grandma did in ‘Oa Mpona’ are displayed in a different style, but the same craft, in ‘Peo e Atang’. The connections are beyond human – they are part of the bigger circle, which is the universe. In this way, whatever I create is a factor from the past, present and future.

My first sculpture ‘Le Bone Lebone’ is a self-portrait from 2016 and you can see it emerge again in 2020 as ‘Ke Bone’. It plays the same role but with slight variations. So in a sense it is all a single view from many eyes.

Atang Tshikare, ‘Ke bone’, 2020

COURTESY: Atang Tshikare / PHOTOGRAPH: Anke Loots

In terms of rewriting history, it’s a cathartic way of looking to the future because our story is something I need to understand; then I can forge my way forward creatively free and with a powerful sense of certitude and ability. Therefore the past and future are intertwined in the present and as such they can be re-imagined in any direction I want.

Sometimes it feels like re-listening to a song I’ve known for a while but then hearing new lyrics or meanings that refresh my views on it, amplifying my love and understanding of the song. Life is like that too.

Atang Tshikare, ‘Setlhare sa Sekaka’, 2021

COURTESY: Atang Tshikare / PHOTOGRAPH: Anke Loots

There are so many ways I’ve learnt how to tell a story that it is easy to see it in many mediums and have it relate to a wide audience without planning it that way.

I guess it’s natural to create a story because it runs in my family and hence I always have them referenced in some way or the other … Yesterday is the beginning of today and tomorrow is the end of today.

Atang Tshikare, ‘Diatla tsa leje’, 2020

COURTESY: Atang Tshikare / PHOTOGRAPH: Anke Loots

BWG: And what do you see, in your tomorrow, the end of your today? You are about to do a whirlwind of shows across the globe. Will ‘Peo e Atang’ be a through line in those shows? Or will it be something you continue to develop on a parallel track? I’m curious how you approach individual works and projects — do you think of them in isolation? Or do you see all of your output as enmeshed, part of a multi-rooted process of probing, gathering, extending?

Atang Tshikare: There are a lot of things coming up and it just gets bigger every year. Mostly big companies and institutes as you can see, it’s great for me!

All in all ‘Peo e Atang’ is a gift from me to my son, so the works for that show are based on the story I’ve worked on.

Atang Tshikare, ‘Peo e Atang’, 2020

COURTESY: Atang Tshikare / PHOTOGRAPH: Anke Loots

There are some similarities in the works outside of the ‘Peo’ show. Creatures like ‘Ke Bone’ and ‘Le bone Lebone’ are the same character but with different forms for example.

But when it comes to commissions like the MET and DIOR — these are about concepts of culture, reasoning and belief. So in that way it is an overarching topic that cascades into the themes I do for my own work. As a creator, my works are intertwined but I still have varying ways of talking about myself within all I do.

Atang Tshikare

COURTESY: Atang Tshikare / PHOTOGRAPH: Kope Figgins