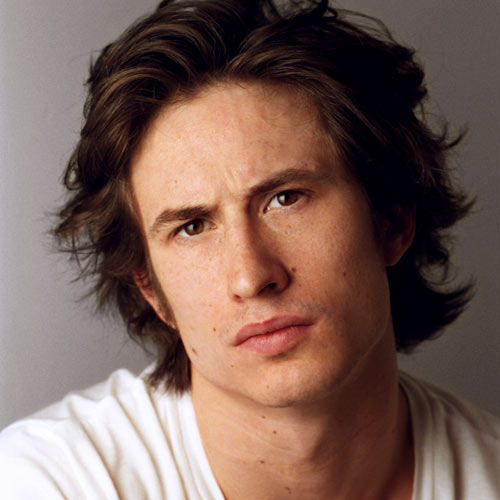

Jeff Martin

Brecht Wright-Gander in deep conversation with the Canadian designer about his work with wood, glass, stone, bronze, concrete – and now ceramics.

Jeff Martin, ‘Excavated Bureau’, 2021 with works from Max Lamb, Maria Moyer and Ian Collings

COURTESY: Jeff Martin

AROUND 2012, THE Canadian designer Jeff Martin was travelling 6,000 miles annually to show exquisitely crafted woodwork at the International Contemporary Furniture Fair. That’s what it took then, pre-Instagram, to gain international visibility. Today, his studio has broadened to include ceramics, glass, stone, bronze and concrete.

Unlike many of the famed leaders of the Studio Craft Movement, Martin continually researches and expands his material vocabulary. George Nakashima was a woodworker. Henry Bertoia was a metalworker. Toshiko Takaezu was a ceramicist. They found what they needed in a single material. How different from today’s digitally native designers who favour heterogeneous assemblages and are agnostic about the virtues of particular materials.

Jeff Martin, ‘Excavated Vessel’, 2021

COURTESY: Jeff Martin

Digital workers often treat pixels and voxels as primary rather than derivative of what they represent – composing visually and then outsourcing the transformation of their renderings into tangible matter. This can have fantastically exciting results and spur innovations in form that more traditional approaches to making would not, however it can also lead to a certain alienation from the non-visual and haptic qualities of materials. A third path is marked by Wendell Castle, who explored a variety of media but whose angle of approach was always deeply informed by tactile knowledge. This is the pattern to which Martin’s practice hews.

Handcraft has an inbuilt conservatism: once you’ve learned a particular technique works, it makes little sense to continue trying novel approaches. The stakes are different when there is no “undo”: experience trumps experimentation. And yet Martin has managed to become both a master of his craft and to retain his curiosity – creating a body of work that reflects an intense focus on specific materialities, as well as a voracious appetite for finding new ways of touching, marking and feeling.

Jeff Martin, ‘Ceramic Hallucination’, 2021

COURTESY: Jeff Martin

Brecht Wright Gander (BWG): I’m going to start by backgrounding your career trajectory and early references – I think we were both coming alive to design around the same time (early to mid-2010s) and under some of the same influences, such as [woodworker] Palo Samko and [design and fabrication company and gallery] BDDW. In many ways, your career tracks the story of the American Craft movement since the millennium. You’ve also been pushing to advance the field while simultaneously performing the miracle of earning a living by making exquisite objects by hand. That’s all stuff I want to get into even before we touch on your latest work with ceramics. So this is a conversation I’ve been looking forward to and which I anticipate will have me arguing about word counts with my editors.

Jeff Martin (JM): Yes, touching on those artists who inspired me early on is great. Definitely Samko and BDDW, but mostly two artists out here – Roy McMakin and Alma Allen -, with some early visits to them in the early 10s. These two artists flow freely between pure design and conceptual/sculptural practices. That really squared me off into material developments being absolutely unchained and being able to work in the liquid media of hardcore industrial design – but then back into art again as well.

Jeff Martin, ‘Excavated Bureau for Brian Rochefort’, 2020

COURTESY: Jeff Martin

BWG: You visited Roy McMakin? Then maybe you’ll know this — is he the originator of the patchwork inlay style? As many readers will know, that became a hallmark of the millennial revival in slab woodworking. There being no history of the contemporary, it is hard to make out just how the currents of influence flow. Patchwork has a variety of precedents, from Japanese Boro fabrics to American Punk couture. Nakashima was one of the great champions of the functional inlay, but he was restrained by a fairly utilitarian ethic – whereas the patchwork style you and others developed relishes contrasts in woodgrain and patterns of figuration. Another signature innovation of yours is using a brass circle in place of a double-wedged butterfly joint. I wonder how you think about the tradition of craft – as something to push against or as something to draw from – because I see both impulses in your work? And what do you make of the aestheticised repair as a leitmotif in contemporary woodwork?

Installation view at the Alpenglow Projects showroom with Jeff Martin, ‘Mesa Table’ and ‘Shaker Desk’, 2020. Other works include: Brendan Ravenhill pendant and small pieces from JB Blunk, Anton Alvarez, Steven Haulenbeek, and Rubeena Ratcliffe

COURTESY: Jeff Martin

JM: Yeah! I had a really amazing trip down to LA in the early 2010s and scored myself an invite out to Joshua Tree to go visit Alma and his robot and team. I remember meeting Dan [John Anderson] who was his shop foreman there, and has since become a good friend. Dan was standing atop a 2′ thick slab about 10′ x 5′ wide of white yule marble carving a donut out of the centre with a chainsaw of sorts. And on that same trip I had the opportunity to go out to lunch in Roy’s hometown of San Diego with him. Both artists I had been in touch with for years, preening for an apprenticeship position, before I landed one with Palo. And both provided so much insight into their practices – and actually had taken a moment to look at what I was doing and offer some constructive criticism. I remember Roy asking me why I was making limited numbered editions, and he said it should only be done if the mould fails or breaks, or else it’s just a marketing tool. It really opened my eyes to practices and ways of thinking where moulds are permitted to change … and how those moments of collapse are preserved in objects, or in practice.

Alma’s humility and constant wonder is really distinct. His work is such an extension of that wonder. And Roy is just incredibly sentient and wise with his approaches. They both offer this gentleness cloaked in bravado.

Jeff Martin, ‘Ceramic Hallucination’, 2021

COURTESY: Jeff Martin

I’m not sure where the patch originated. But I love that they both were doing it in this very analogous interpretation of the digitisation of craft. All of the craft being so present and unafraid to move into the future. And like any good woodworker I got to go out to New Hope and walk through Mira Nakashima’s studio, formerly her fathers. She is also such an incredible visionary. Preserving the legacy of workmanship her father developed, and contributing her own language to it.

Our own use, here in the studio, of patches and bronze rings has always been intended to be an offering of our own prose to the vocabulary of craft. And really served as the jumping off point for me personally to begin opening my mind, hands, and heart to other materials and creating new ways of making things.

Jeff Martin, ‘Ceramic Hallucination’, 2021

COURTESY: Jeff Martin

BWG: You describe patchwork and bronze rings as a “jumping off point” and I wonder if I’m reading too much into that when I ask if you don’t feel that you’ve left that behind? I probed this in my last prompt and perhaps you dodged it intentionally, but I really am interested to hear your thoughts on the tradition of craft, which has never been static but which does involve a conservative partiality for tested methods and means, against the impulse to explore and innovate. Your studio seems exemplary in the way it gives energy to both of these drives – and perhaps they are not even so distinct, for you, as I’m describing?

To continue another line of conversation, you described patchwork as an “analogous interpretation of the digitisation of craft.” That brings to mind another thing that patchwork can look like – which is pixilation. I’m interested to hear you unpack your thoughts on this in concrete terms, particularly since some readers may not be familiar with the techniques and machines involved.

Jeff Martin, ‘Painted Credenza’, 2021 with works from Dan John Anderson and Maria Moyer

COURTESY: Jeff Martin

JM: I adore craft. I love the technical prowess and sensitivity to materials that the foundations of craft lay atop. I love the history of craft and even the teaching of craft in a mentor/apprentice relationship. We are able to transmit the entire gestalt of human craft and endeavour through patiently trained apprenticeships, so that generationally we get better and smarter at working with our material.

But I feel that significant portions of the craft community stand in unity against this fact. It is too often we hear colleagues championing “only solid wood” when shop-sawn veneers are a better long lasting, stable, and ecologically sensitive approach for cabinet doors. Or when some person grabs an audience to talk about the perils of robot-aided production, that it has no soul. It’s so fundamentally discouraging to hear these points of view and I think they are paraded about when people are fearful of change, or simply don’t know enough about craft to adopt practices of today and look to tomorrow.

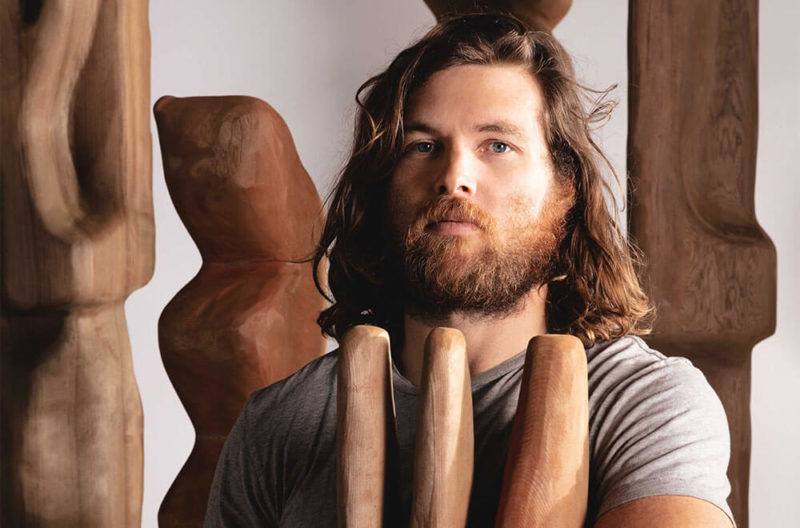

Jeff Martin, ‘Ceramic Furniture’ at Tiwa Select, 2021

COURTESY: Jeff Martin

CNCs are stupid robots, they do what you tell them to do. Solid wood is great for some things – and incredibly selfish and impractical for others. Making something look “wabi sabi” is not in itself a wabi sabi approach, which I think is fairly punk rock at its core, you are simply capitalising and profiting on the backs of people who challenged the contemporary thought of their time.

So at our studio we synthesise these emotional responses and do things which are craft forward, stupidly handmade, ridiculously beautiful craft. And then also we make things on an industrial scale at a plant that produces highway medians – accessing a level of craft which is focused on heavy industry. And we approach work at an anti-craft level, like our ceramics. Which doesn’t even wade into the waters of the dogmatic “rules” of clay culture at all. I do it all because I love craft, and respect it.

Jeff Martin, ‘Ceramic Hallucination Constellation’, 2021

COURTESY: Jeff Martin

I had an interesting conversation with Marc Benda once and was showing him some of my glass work. His response was incredibly thoughtful, and he educated me on getting immersed in the volume of glass culture and to look to Italy and Murano to understand how much was being done before me. I was a little bummed out that he was not interested in the work, because I adore his gallery. But I also got so elated when he couldn’t figure out how I made my glass work. It made me realise that having polarising and challenging work is a great asset. It doesn’t have to be beautiful if it is interesting and engaging.

Jeff Martin, ‘Excavated Vessel in Blown Glass’, 2021

COURTESY: Jeff Martin

Regarding your second question, when we lay out our patches we are trying to make the work look like it’s coming together, loading in a computer, pixelating to become a unified object, made of misplaced and random parts. So we often use the offcuts of the particular wood slab we are working on to create the patches from. It speaks directly to the digitisation of craft. Shop drawings made on a computer. CNC robotics. Power hand tools. I love all of it. And to me it is all our way of producing handmade objects. I remember hearing someone talk about it, like it was made by machines. Well, no woodworker is born with hand saws and routers for arms and legs. We all rely on tools, and the biggest tool we have is our minds. So why not deep dive into it?

BWG: I take it you’re talking about your concrete ‘Neolith’ stools when you refer to working with a company that produces highway medians? What’s it like dealing with them? I’ve found that one of the curious things about running a small studio is that few other companies are equipped to interface at our scale. For most industrial outfits the prospect of producing just a few of something and doing it with a high level of detail looks like throwing money into a cement mixer. I also wonder what you can tell me about shifting between these diverse registers of production – from the intentionally naïve, to the expert but arduous, to the industrially outsourced? What motivates you to stretch across those distances when it would surely be more comfortable, from a conventional business perspective, to stay in a single lane?

Jeff Martin, ‘Travertine Neolith’ stool, 2021

COURTESY: Jeff Martin

JM: Yes, we really seek out opportunities of scale with our collaborations with heavy industry, for instance we work with a concrete casting operation, a bronze casting operation (which is a former auxiliary supply chain of the Canadian Autoworkers union), and a pipefitting company that we employ for seven axis robot carvings. Not everyone wants to work with us, but the companies that do are very open to new opportunities. We approach it earnestly, openly and with a friendly attitude – and it goes a long way.

I once thought I could have my own foundry and forge, and concrete facilities, and glassblowing operation, and woodworking shop, and on and on. But I would never have the time to master all of the techniques. Nor do I really feel the need to be a master of any of these practices. I have always felt that learning the principles and then figuring a path from there is the best way forward. So I love working with experts in their respective fields. It helps me learn and pushes me to design to the specific restrictive parameters of their tooling capacities.

I should note I also am diagnosed with ADHD, and so I absolutely must be working on several different projects, in several different materials, across several different vendors, with several different ideologies at play at all times. I don’t have a choice in this matter! And it’s been a wonderful thing for me. My demand is that I am involved in all levels, but not making everything start to finish on my own. So this works well for a small business the size of ours, and really gives me an exceptional satisfaction in my work and life. My most recent material focus has been on ceramics.

Jeff Martin, ‘Sarophagus 1’, ‘Excavated Bedside Table’ and ‘Stoneware Constellation’, 2021

COURTESY: Jeff Martin

BWG: You mentioned that you’re approaching ceramics from an “anti-craft” level. I’m curious what that means to you. Your studio is known for exquisitely rendered fine woodcraft. Speaking broadly, wood isn’t a material that rewards naiveté; if you don’t plan ahead for the innumerable ways it can expand, contract, cup, and bow, cracking results. Woodwork is also reductive – once you make a cut it becomes very difficult to add back – so rigorous planning and staging are critical. In your ceramics it looks like you’re seeking release for a more immediate impulse. Gesture is something that you’ve brought into your work before – for instance with your oxidised cabinet fronts when you activate the wood tannins to release colours, making the material both canvas and paint at once. And chance has appeared in your work before – as with your excavated glass vessels, when the forms are only partially defined in advance. But forms like those of your latest ceramics, that feel fluidly responsive to impulse, haven’t been part of your vocabulary before (to my knowledge). Tell me about the decision to take up clay and what it means to be “anti-craft” in your handling of it.

Well, with clay I definitely did some research. I read a few books on the fundamentals of ceramics as materials. So stepping into the arena, I knew what processes we were going to use in the general sense of using kilns safely and what to expect out of the specific clay bodies. But that was it. The idea was to stand at the edge of something with enough naivety, enough confidence, enough humility, and enough funding to be able to work quickly through thoughts.

Unlike carving stone, or planning wood fabrication, I permitted myself to release thoughts as quickly as possible in the form of shapes and movements. Which to me is precisely how clay should be worked unless you are firmly rooted in a craft movement. The physical output and gestures had this really vague sense of being playful apertures of psychedelia. Which has tied right back into where I am at in life right now. Wanting to express emotions and wonder without language, but with movement and connection to the earth. So the title of the wall-hung objects is ‘Hallucinations’.

Jeff Martin, ‘Ceramic Hallucinations’, 2021

COURTESY: Jeff Martin

And then I really was starting to work clay every single morning as a warm up for my studio duties. And in that I found making tiles to be extremely therapeutic. I had no goal for the tiles other than manipulating each tile to be its own micro sculpture. When I had amassed a thousand or so of them I realised I should probably tie it back to who I am at work, and that’s a cabinetmaker. So I decided to make these treasure chests for all my own little objects I collect. Talismanic works from some heroes like Takuro Kuwata, Anton Alvarez, Ian Collings, Roger Herman, Max Lamb, Maria Moyer, Sigve Knutson and more. Hopefully some of yours someday too as I know we have discussed trades! So we started calling the works ‘Sarcophagus’ for their spirit of holding the objects you cherish in your life to spirit them away with you once you go.

Jeff Martin, ‘Sarcophagus 2’, 2022

COURTESY: Jeff Martin

I should also mention my good friend Tyler Goin who I started doing this work with, sharing space and time making our own objects and just engaging in creative work with friends for socialisation, rather than going out for drinks or something like that. So my clay work is deeply personal and has been a way for me to engage in art as therapy in a way. I really have no hopes for the works though I am thrilled they are being acquired. Through my work with clay I have become more confident as a person, and a designer, who can be quite polarising. And I really am embracing the fact that people may hate my work or they may own it. But it’s not meant for everyone.

Jeff Martin, ‘Sarcophagus 1’, 2021

COURTESY: Jeff Martin

BWG: For those it IS meant for – and considering that your collector list is a compendium of design aficionados, that’s going to include a lot of TDE readers – where can we see your work in person? What projects should we look out for in 2022?

We are going to be exhibiting one large ‘Sarcophagus’ at an upcoming show in the Egg Collective space in January in Manhattan. And I am currently building two more Sarcophagi and ‘Hallucinations’ to get into the hands of our gallerists Jeff Lincoln and Tiwa Select. And of course, we will be adding more robust inventory to our own stock – and if you happen to be in the Pacific Northwest our gallery is always open and I would be happy to serve you a Kombucha and chat about work any time. We’re likely to be doing some more shows for our more serial production at Matter in New York, Spartan in Portland, and Brendan Ravenhill’s space in East LA later in 2022 as well. So much stuff coming up, and a lot of growth in our team and operability – so I am really looking forward to 2022.

Jeff Martin

COURTESY: Jeff Martin