Michael Anastassiades

The Design Edit meets the lighting designer as he reflects on twenty years of experimentation and distillation.

Michael Anastassiades, ‘Arrangements’ for Flos, 2017

COURTESY: Michael Anastassiades / PHOTOGRAPH: Santi Caleca

YOU MAY WELL know Michael Anastassiades as one of the world’s foremost lighting designers, who creates rigorous designs to order, under his own name, and equally refined production pieces for the Italian lighting giant, Flos. But for a number of years, he was also a yoga teacher.

Michael Anastassiades, ‘Spot Stool’ for Herman Miller, 2016

COURTESY: Michael Anastassiades / PHOTOGRAPH: Ben Anders

“At first, I started practising Ashtanga because it gave me the distance I needed from design,” he says. “And then when I started teaching it, from the late 90s, it provided an income and alleviated the pressure to find a job in a design studio, where I didn’t think I’d fit in anyway.” Indeed, though his name is now synonymous with perfectly formed lighting based on lines and circles (a system that has spawned a whole industry in cheaper copies) his work ranges much further afield. He is not the easiest of designers to put in a single box.

Michael Anastassiades, ‘Coordinates’ for Flos, 2019

COURTESY: Michael Anastassiades / PHOTOGRAPH: Tommaso Sartori

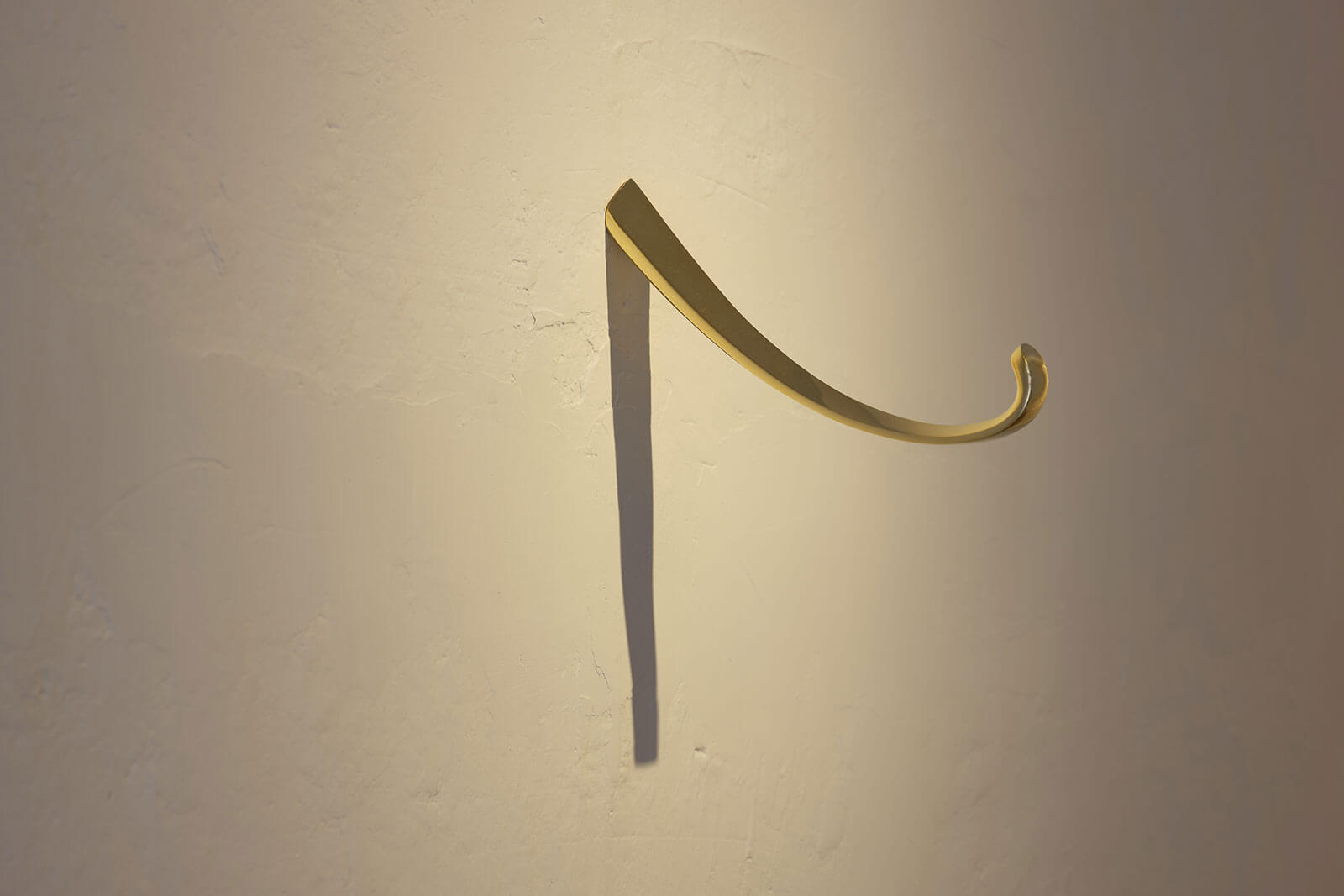

A journey around Michael’s freshly made website (designed by artworld favourites A Practice For Everyday Life) reveals a practice that takes in intriguing conceptual objects, including a lightly curving brass hook (from the ‘Silver Tongued Blah Blah’ collection) and a perfectly round pebble, cast in bronze with a white patination. Both are limited editions, made under the aegis of Tokyo’s Taka Ishii Gallery.

Michael Anastassiades, ‘Blah Blah Blah’ for Taka Ishii Gallery, 2019

COURTESY: Michael Anastassiades

Then there is a handbag for Valextra, launched in September 2019, stripped right back to bag basics, and made in the very smoothest leather the company uses. Its long strap is embedded with fiercely effective magnets, so however it is grabbed, it will clamp soundly onto the bag in a new, safe configuration every time. A series of small marble tables for the art collector Nicoletta Fiorucci’s home of Li Galli are representative of the three tiny islands in this archipelago off the Amalfi coast; they are like abstract pieces of poetry with a wordly function nonetheless.

Michael Anastassiades, ‘Li Galli Islands’ commission, 2015

COURTESY: Michael Anastassiades

“Just before lockdown last March, I’d got into a really good place where I could focus more on the creative side of things”

Michael Anastassiades, ‘Li Galli Islands’ commission, 2015

COURTESY: Michael Anastassiades

“I’m hoping to go back to that. I don’t want the business to grow any more. I just want to do less, better.”

At the Royal College of Art in the mid-90s, Anastassiades’s work tended towards the experimental. He had already graduated with a degree in civil engineering from Imperial College, and before that done military service in his native Cyprus. No wonder he felt it was time to play. His graduation project included dainty plywood cups that could hold voice messages in their bases, and a table containing an alarm that would rattle you awake at an appointed hour.

Michael Anastassiades

COURTESY: Michael Anastassiades / PHOTOGRAPH: Eirini Vourloumis

“I felt quite unemployable back then,” says Anastassiades, “because it wasn’t easy to define quite what I did. It wasn’t art, it wasn’t furniture.” From 1997-98, he even designed the scenography for Hussein Chalayan’s fashion shows. “It was only in 2006 that I said, ‘OK, I’m going to produce some real stuff’ – and it was an almost instantaneous success.”

Michael Anastassiades, ‘Half Way Round’ for Dansk Møbelkunst, 2018

COURTESY: Michael Anastassiades

He made mirrors out of single pieces of highly polished copper and vases shaped like a blowing ball in the same material. Then in 2007, he formally established his company and committed to lighting. The first series included a chandelier made from three linear tubes in an umbrella arrangement. Since then, his work has been clearly identified by the use of straight lines, linear bulbs, glass spheres and interlocking circles – like drawings in space. “I like the idea of functionality with the minimum material,” he says. “If you took away just one thing it would stop existing.”

Michael Anastassiades, ‘Arrangements’ for Flos, 2017

COURTESY: Michael Anastassiades / PHOTOGRAPH: Santi Caleca

Anastassiades has a beautiful studio in north London, top-lit, airy and right next to the painter Paula Rego who always pops into studio parties – “she likes to come early for a quick glass of champagne,” he says. But we decide to meet at his home near Waterloo Station, where large-scale paintings by Camille Henrot and Enrico David once again reflect his love of the power of the line. Both artists are able to tell strong stories with the sparest of outlines.

-

Michael Anastassiades, ‘String Lights’ for Flos, 2013

COURTESY: Michael Anastassiades / PHOTOGRAPH: Guiseppe Brancato

-

Michael Anastassiades, ‘String Lights’ for Flos, 2013

COURTESY: Michael Anastassiades / PHOTOGRAPH: Guiseppe Brancato

Above his walnut dining table – newly waxed and almost red in colour, that he designed for his own home, and can be made to order by his studio – hangs a ‘Vertigo’ light. A pendant design, it is composed of just two elements – a vertical and a horizontal – in anodised aluminium, and can be brightened or dimmed.

“You need multiple light sources in a home, or a bar, or an office even,” says Anastassiades, dimming the ‘Vertigo’ by gently touching its horizontal bar with his finger. “And I hate the idea of controlling it all from a central panel, or from your phone. It kills the whole experience of how you move through a space, and turn it from dark to light. You should embrace a place as a living thing. It’s not a computer programme.”

Michael Anastassiades, ‘In Between The Lines’ for Taka Ishii Gallery, 2019

COURTESY: Michael Anastassiades

For the designer, lighting is both a spatial and experiential consideration. “The way it exists in nature is really magical, and irreplaceable,” he says. “But you have to study it and understand it in that context first. When you make an artificial illumination, you have to accept that it’s different. You’re not trying to make night into day. You have to embrace darkness first, then you can start designing light.”

Michael Anastassiades, ‘Large MC7’ at Erdem Store in London, 2015

COURTESY: Michael Anastassiades / PHOTOGRAPH: Alexandros Pissourios

A series of one-off commissions illustrate this well. For the Four Seasons in New York, which opened in 2018 at its new East 49th location, he established a grid of lighting that could change in density and layering, to work differently across the restaurant’s various zones – entrance, bar, restaurant. “Isay Weinfeld, who created the interior, had never given away the lighting design before,” says Anastassiades. “It was a very ambitious project, we worked on it for a year.”

Michael Anastassiades, ‘Coordinates’ at The Four Seasons, New York, 2018

COURTESY: Michael Anastassiades

For the tables, he designed a rechargeable lamp called ‘Last Order’ which diffuses light through its solid crystal base. And though the restaurant itself did not last long (the grandeur of the Philip Johnson original, designed in 1959 proved a hard act to follow), Flos picked up the table lamp design and it is now a production piece.

Michael Anastassiades, ‘Last Order’ at The Four Seasons, New York, 2018

COURTESY: Michael Anastassiades

In 2016, Garance Primat, heir to the Schlumberger fortune, asked Michael to find a lighting solution for two rooms at her magical elite-hotel chateau of Domaine des Etangs in the Aquitaine. For the 19th century oval salon, he created a giant egg in pale-gold mouth-blown Murano glass; and another the size of a real ostrich egg for a second room. While they suffuse light at night, during the day both become exquisite pieces of sculpture, their satiny surfaces delicately reflecting any available light.

Michael Anastassiades, ‘The Large Philosophical Egg’ commission, 2019

COURTESY: Michael Anastassiades / PHOTOGRAPH: Rene Habermacher

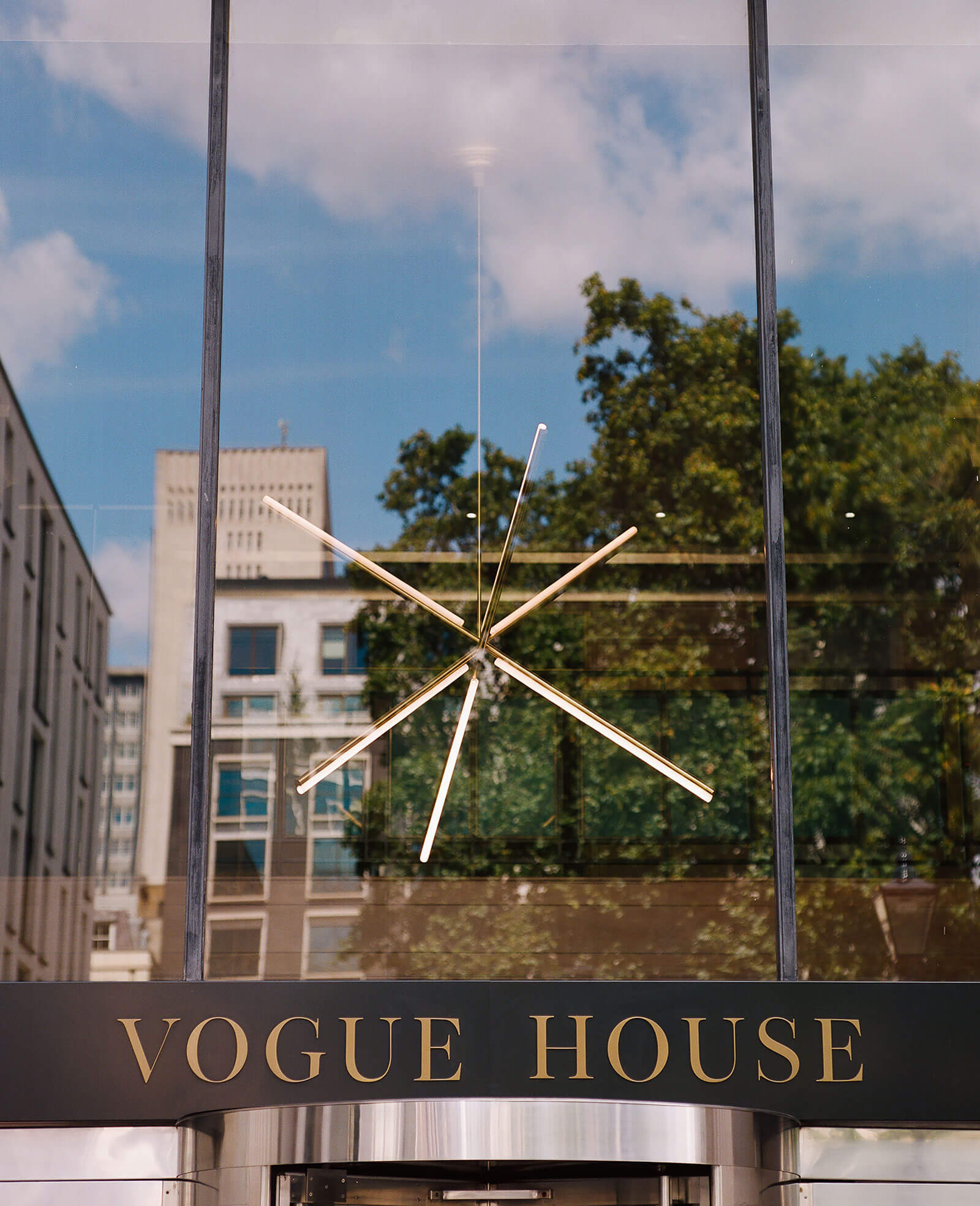

A stunning five point star, originally created for Brioni two years ago has now found a home in the foyer of London’s Vogue House. And visitors to Erdem’s flagship store in Mayfair will find a four metre version of the ‘Mobile Chandelier’ family – an architectural intervention that connects the two retail floors of the town house as it drops down the elegant stairwell.

Michael Anastassiades, ‘XYZ’ commission at Vogue House, 2019

COURTESY: Michael Anastassiades / PHOTOGRAPH: Alexandros Pissourios

While Anastassiades’s year hasn’t been any less strange than anyone else’s, it has certainly been busy. Private commissions in the Hamptons, New York and Berlin of a previously unseen scale have come into the studio, and thanks to the fact that five years ago he bought out the warehouse in Birmingham which had been doing the assembly for his own pieces, he has been able to fulfil them. “The owner retired and we took a drastic decision to bring everything in-house. Now we’re responsible for our errors, and our successes,” he says. There is more work on the table for Flos, and two exhibitions are pending.

Michael Anastassiades, ‘Love Me, Love Me Not’ for Salvatori, 2017

COURTESY: Michael Anastassiades / PHOTOGRAPH: Germano Borrelli

One is of his own work at the ICA in Milan, which is slated for September. Another is a show that he is curating for the MAK in Vienna, of pieces taken from the biggest private collection of Wiener Werkstatte works, which should open in October. “Just before lockdown last March, I’d got into a really good place where I could focus more on the creative side of things,” he says, “and I’m hoping to go back to that. I don’t want the business to grow any more. I just want to do less, better.”

Michael Anastassiades

COURTESY: Michael Anastassiades / PHOTOGRAPH: Ben Murphy