Pae White

Shimmering, glittering, sparkling, iridescent – her extraordinary work is inspired by colour, nature and the potential of the loom.

Pae White

COURTESY: © Pae White / PHOTOGRAPH: Enrico Fiorese

“I WAS TALKING with a friend about the places I miss,” says the multimedia artist Pae White, “and it made me think. I don’t miss Paris … in fact, the places I’ve been missing are Ghent and Guadalajara – where I make work.”

White is speaking over Zoom from Sea Ranch (a small beachside community 100 miles or so north of San Francisco and a nine-hour drive from her home and studio in Los Angeles), where she has been for twelve months. It is the first time since childhood that she has not left the state in a year. But though it looks idyllic – visible through the window behind her is an ultramarine Pacific breaking on a rocky shore – it’s not the ideal location from which to be supervising the installation of an exhibition in Germany, let alone weaving a giant tapestry on a loom in Belgium and producing a series of sculptures in Mexico.

Pae White, ‘Guide H’, 2020

COURTESY: Pae White and neugerriemschneider, Berlin © Pae White PHOTOGRAPH: Jens Ziehe

The show, which was almost ready when the world locked down, is now opening on 30th April to coincide with Berlin’s revived Gallery Weekend. But rather than stick with what she’d originally planned, she has used this lost year to rethink the exhibition. “It’s changed so much from what it was going to be,” she says. “There are certain aspects of [the past year] that have been really useful.” Alone with her computer rather than with teams of assistants and fabricators, “it’s offered an incredible amount of clarity. And many things” – not least the importance of nature – “have been put in perspective.”

Stretching across an entire wall of the gallery the dominant work promises to be a “monumental” tapestry. It is still on the loom when we speak, so its dimensions are uncertain. But its name is ‘Solastalgian’ – referring to the sense of desolation people can feel about environmental change. “Being up here in California with the wildfires, rain is on everybody’s mind all the time,” she says. “It’s a really vulnerable place, and this is a kind of homage.”

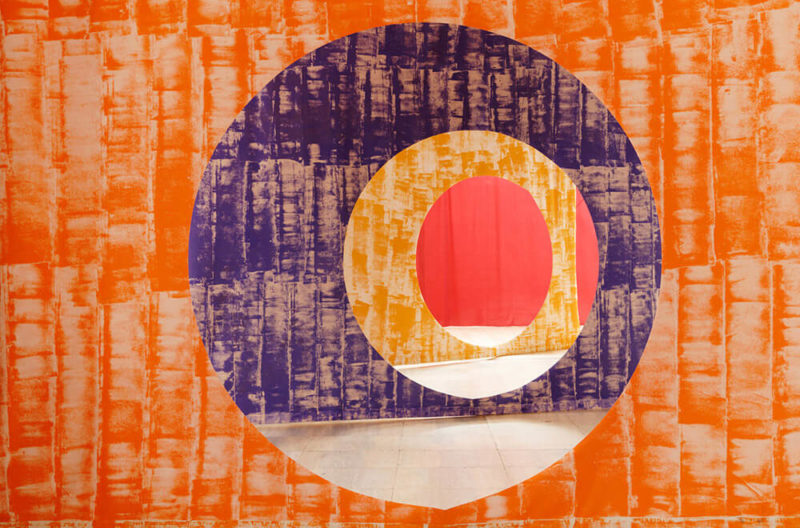

Pae White, ‘Solastalgian’, 2021

COURTESY: © Pae White and neugerriemschneider, Berlin / PHOTOGRAPH: Jens Ziehe

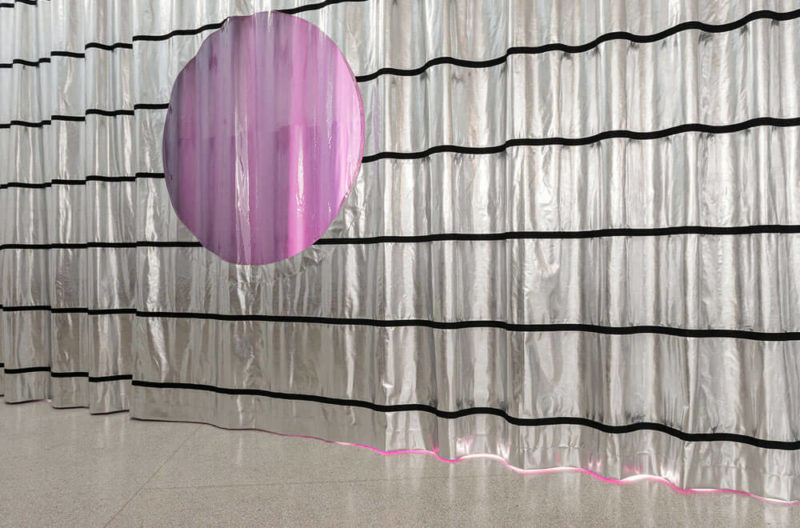

If the tapestries for which White is best known – the curtain in the Snøhetta-designed opera house in Oslo, a highly theatrical, almost trompe l’oeil evocation of crumpled aluminium foil that shines like metal despite being woven from cotton, wool and polyester; or her images of curls of smoke – have an almost photorealistic quality, this one is more of an abstraction of clouds and rain.

Pae White, ‘metafoil’, 2008, the main stage curtain of the Oslo Opera House

COURTESY: © Pae White / PHOTOGRAPH: Hélene Binet

“It’s almost like the rain is articulated by the warp, which runs vertically,” she says. “We’ve created weave constructions, using a lot of metallic thread, that feel almost like chains. It’s all fabric, but I want it to feel like jewellery. And even though it’s woven on this big industrial loom, a big oily beast that’s super loud and ten foot [300cms] wide, I want it to look as though it is something made by hand, something embroidered.”

For White, it’s not the actual weaving (which is mechanised) that takes the time, it’s developing the computer files, she says, explaining that in pre-pandemic times she would go to Ghent with a programmer. “It is the dreamiest thing, one of the most extravagant pleasurable things I can imagine, to book the loom for a week and just sit there and improvise and tweak the files and run them again to see what happens. It’s just fantastic.” Unable to travel this year, she has had to rely on video calls and couriered samples to gauge its progress. “It’s a lot harder to adjust the tension [remotely], and the variables are so huge,” she says, citing, for instance, the difference in tension between cashmere and cotton. “And there’s also been trouble because a lot of thread companies are going out of business.”

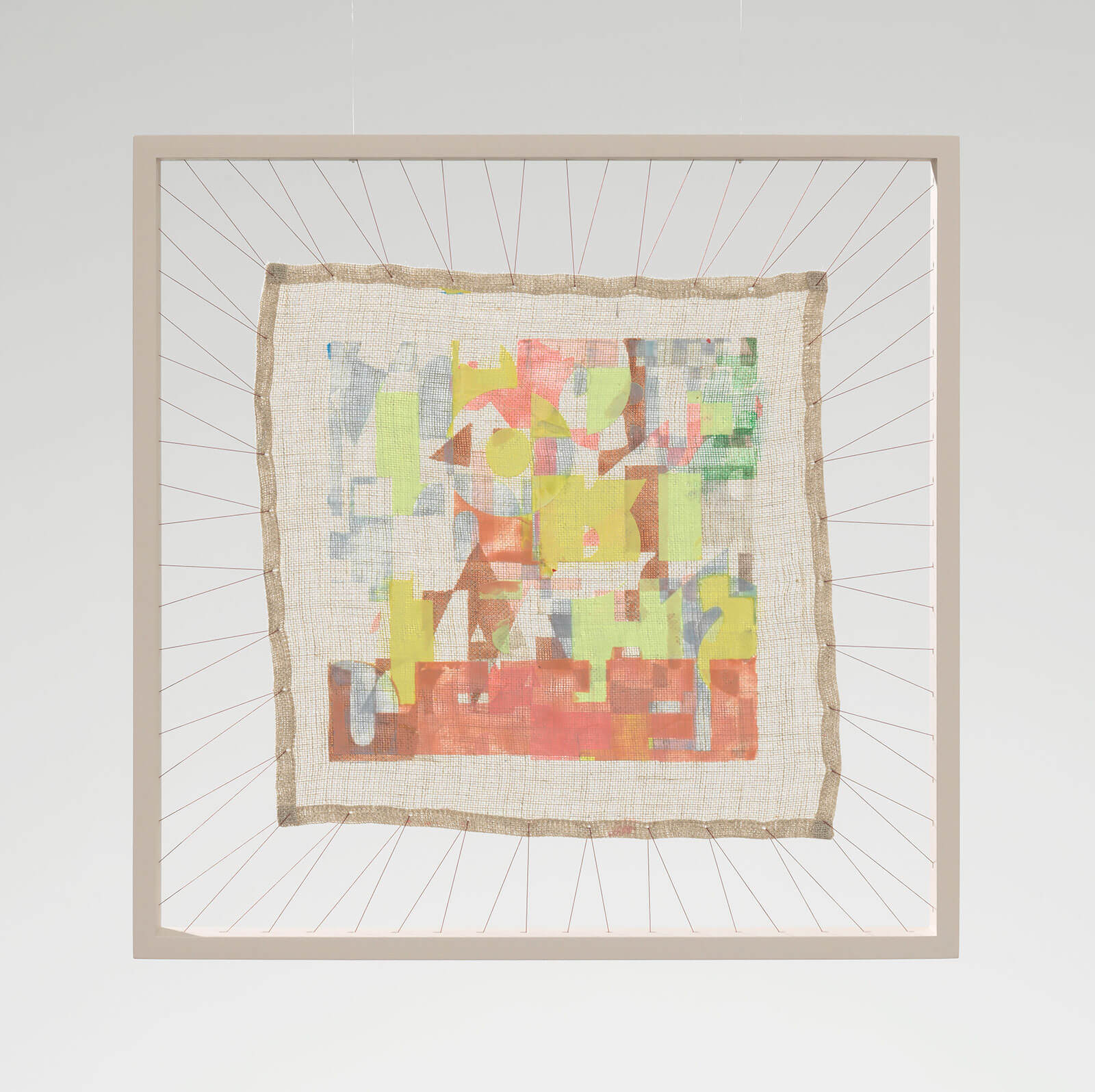

Pae White, ‘Chimera’, 2021

COURTESY: Pae White and neugerriemschneider, Berlin © Pae White / PHOTOGRAPH: Marten Elder

Sometimes, though, a change in thread is intentional. “We’ve deliberately programmed in abrashes,” she says (‘abrash’ being the Farsi word for ‘rainbow’ or ‘ spectrum’, which in the world of Persian carpets refers to a subtle variation in colour caused by the introduction of thread from a different dye batch). With ‘Chimera’ they go from “golds to silvers to multicolour, and then back. I’ve always loved those shifts. And [with Solastalgian] it just feels like something’s changing within the rain.”

In addition to the tapestry wall, there’ll be another covered entirely in tiles: squares, circles and semi-circles of vibrantly coloured, densely patterned ceramic-like abstract bas reliefs that gleam with an “unbelievable iridescence”, the result not of a metallic glaze but “a sort of sub-atomic process I don’t fully understand” called physical vapour deposition (PVD). The process exposes the fired clay to such pressure than the atoms, ions or molecules within the coating fuse with the surface it’s been applied to. “The minute I saw it on the pieces we tested, I just had this visceral reaction,” she says. “It was just so magical. I’d never seen anything like it.”

Pae White, ‘Middlefauna’, 2021

COURTESY: © Pae White and neugerriemschneider, Berlin / PHOTOGRAPH: Jens Ziehe

The tools with which she works on the clay could hardly be more ordinary. “I go to the 99 cent store and just buy things that will make a nice impression: toilet-paper holders, clothes pins, Sharpies, anything really.” The more faceted the surface, the greater the area to be coated and the potential to “magnify and maximise the reflectivity in the colour shifts”.

But though “PVD feels like the future,” she comments, “it’s very important to me to maintain a studio where things are done by hand,”and she is reluctant to get too bogged down with the technology. “There are a lot of things I use that I don’t have any idea how they work. I have to find people to help me. But I feel that if I knew too much I might get too caught up in its limitations.” Better to view it as something alchemical, even magical. (‘Enchanted’ and ‘enchantment’ are words she uses a lot.)

Ultimately nature is more integral to her work. As a child she collected cats’ whiskers, spiders’ webs and flies, all of which she has made use of in her work. “Maybe it’s a Californian thing, growing up in the yard when you’re a kid, poking around and collecting bugs. You think they’re your friends.”

Pae White, ‘False Negative’, 2021

COURTESY: Pae White and neugerriemschneider, Berlin © Pae White / PHOTOGRAPH: Jens Ziehe

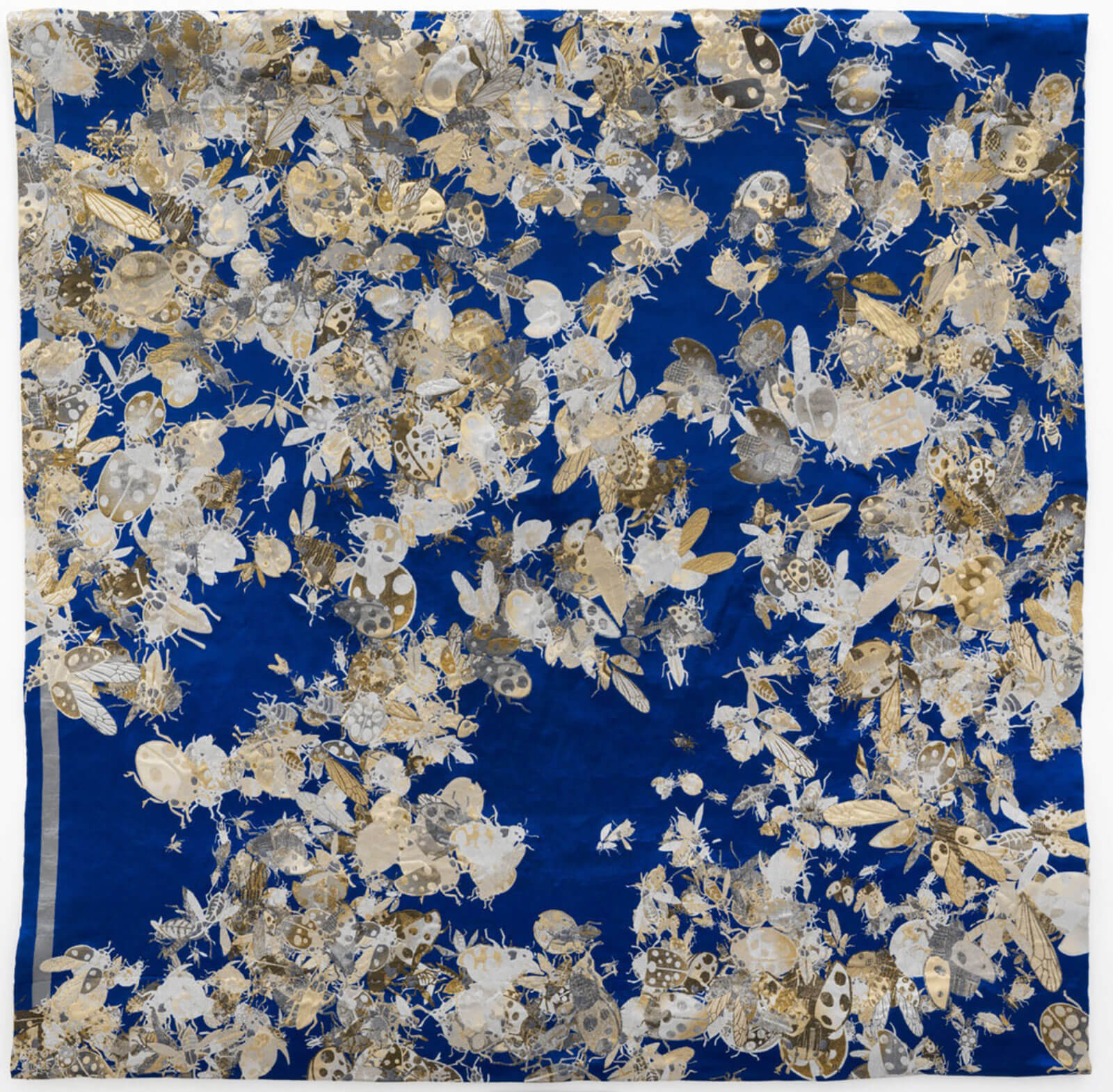

Her tapestry series ‘Bugs + Drugz’ features images of ladybirds, dragonflies and grasshoppers amid a jungle of plants that produce psychotropic drugs. And bluebottles, in particular, are the “long-time obsession” to which her enduring interest in iridescence might be traced. Witness the handbag she was commissioned to design for Christian Dior in 2018, which took as its inspiration the story of the spider and the fly, hence the web and embroidered spider concealed from public gaze within its quilted velvet interior, stitched in iridescent thread to complement its dichroic calfskin casing. “And I really, really want to make flies out of cloisonné or iridescent enamel and just have chains and chains of them as jewellery,” she adds.

Pae White, ‘Bugs w/ Silver Abrash’, 2018

COURTESY: © Pae White and neugerriemschneider, Berlin / PHOTOGRAPH: Jens Ziehe

She also loves the iridescence of an abalone shell, “which I find all the time on the beach. It’s a huge discussion here because the kelp forest has collapsed and that is what it survives on. There’s an infestation of sea urchins that are eating what little kelp is left, so the abalone are starving. Every time I see a shell I wonder if it’s the last I’m going to see.” She has also been gathering fragments of crab carapace, some of which she has worked into the textiles she has made for this show.

White has been foraging for mushrooms too: not for eating but for making dyes, and produced yarns in every colour of the rainbow bar green, in myriad shades. “I was hoping to be able to use them too, but I didn’t get enough. It’s going to have to be something in the future.”

Pae White, ‘Qwalala’, 2017

COURTESY: © Pae White and Le Stanze del Vetro, Venice / PHOTOGRAPH: Enrico Fiorese

In the meantime, she has also been designing seat fabric for buses in the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s Metro fleet. “It’s the biggest project I’ve ever done and it’s ongoing as they do more buses,” she says. “I just like the way it goes on and on but doesn’t have a lot of structural requirements and has no volume.” From her perspective, it is just about colour and pattern.

By contrast, some of the sculptures intended for the Berlin exhibition have turned out too heavy for the gallery’s floor so won’t be in the show. Made in Guadalajara, in Mexico, these monumental talismanic pieces are carved from stone that from certain angles take the form of animals – turtles, bison, bats, frogs – so as to seem both figurative and abstract, ancient and modern. “Guadalajara is only a couple of hours away, and I used to be there a lot, making trips to make refinements. I’d get all these ideas there and see all these possibilities,” Pae explains, “You experience a place quite differently if you’re making things.” Quite apart from the fact that it’s a whole lot easier to supervise the fabrication of a work if you’re there, on site, rather than working remotely. “Maybe that’s why I’m thinking of other places all the time,” she reflects.