Stuart Haygarth

“A lot of my work is about abandonment and loss, I think. And giving things a second life.”

Stuart Haygarth with ‘Comet’ chandelier, 2022

COURTESY: Stuart Haygarth / PHOTOGRAPH: Jake Fox

FOR STUART HAYGARTH, debris is the starting point for new design. The designer’s ‘Comet’ pieces, for instance, poetic and strikingly effective – whether streaking across the foyers of corporate headquarters, or hanging from the ceilings of private apartments – are formed from recycled acrylic ice chunks, used in photography shoots to substitute for real ice. Meanwhile, his ‘Flame’ series of chandeliers, currently on view in Aspen, Colorado, are composed of vintage amber glassware – upturned jugs and vases, saucers and bowls found on eBay – and then threaded on to vertical brass rods so that each strand evokes, he says, “the shape of a flickering flame.”

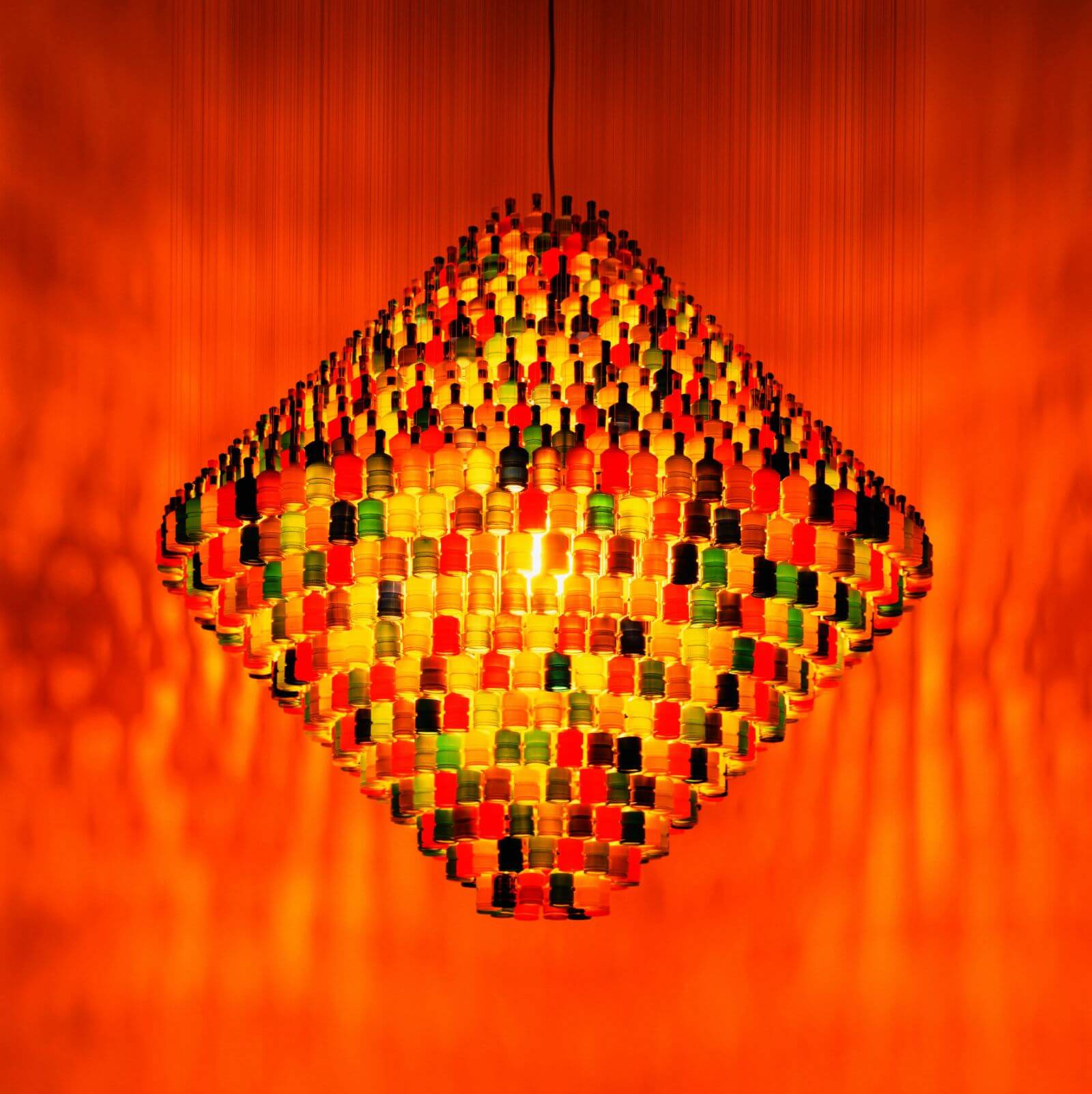

Stuart Haygarth, ‘Flame’ chandelier, 2018

COURTESY: Stuart Haygarth

Haygarth traces his love of other peoples’ detritus back to 2000. As the new millennium dawned, he took his dog for a walk along the South Bank of the Thames in central London. The ground was “a field of spent party poppers,” he recalls. “It looked amazing. They’d all been exploded at exactly the same time to celebrate the New Year, and I thought this represents a significant moment in time, so I got some binliners and went back and picked them all up.” It took him five years to realise, but the result was his ‘Millennium’ chandelier, an 80cm-wide pendant light composed of exactly 1,000 brightly coloured plastic canisters suspended on monofilament fishing line. The piece hangs in the shape of a diamond but assumes a shifting organic form in a breeze.

Stuart Haygarth, ‘Millenium Chandelier (Coloured)’, 2005

COURTESY: Carpenters Workshop Gallery

It also marked a watershed in his career. Having trained in photography and forged a career as an illustrator, Haygarth resolved to start working in three dimensions, “making stuff I really wanted to make.” The results are small editions of light installations and furniture constructed from found objects that are both functional and suffused with meaning. “Narrative is very important to me,” he says. “I don’t just want to make nice things that look good. There has to be a concept.”

The ‘Comet’ series, for instance, came about through an initial commission from Coca Cola. “They wanted something for their foyer in London – something ‘out of this world’ – that’s what they said,” Haygarth explains. “So my starting point was a comet, made out of ice and rock in real life, and the trail you get is just the water evaporating or the ice melting. I thought this was a nice combination … When I drink Coca Cola, which is only when I have a hangover, it’s always with ice. So the idea is to make this comet coming down from the ceiling made from ice …”

Stuart Haygarth, ‘Comet’, 2014

COURTESY: Carpenters Workshop Gallery

We meet at his east London studio in a sparsely furnished white room. From the ceiling hangs one of his ‘Flame’ chandeliers, shortly to be shipped to a collector in California. On the plywood shelves is a neat arrangement of decorative vessels cast in milk glass, destined for use in another chandelier. On the floor stands an orderly tower of cardboard boxes, neatly labelled ‘spectacles’ and ‘unprepped plastic’. “I’ve always been tidy,” he says. “I feel more at ease if things around me are in order, I think, because I don’t feel tidy in my head. I can’t work in chaos.”

The spectacles – sourced in exchange for a donation from a charity called Vision Aid Overseas, a charity that used to export redundant eyewear to developing countries – are the basis for various chandeliers he’s designed. Those he calls ‘Optical’ are made from the lenses, which refract light differently according to their thickness. Others, named ‘Spectacle’, are made from the frames. And some use just the arms and call to mind the spikes of a sea urchin. “I feel like a butcher! I use every part. There’s even a big box of screws.”

Stuart Haygarth, ‘Spectacle Chandelier (Large)’, 2006

COURTESY: Carpenters Workshop Gallery

Strikingly beautiful in the way they reflect and refract the light source at their hearts, there is also something haunting about them. “When I first showed the ‘Spectacle’ chandelier in Paris, this old French guy came up to me and said, ‘It reminds me of the Holocaust.’ I’d never thought about that at the time, though I had been to Auschwitz and seen all those piles of glasses. But I hadn’t intended the association.” Rather it was the “history” inherent in each pair that captivated him, the fact that “somebody had used them to see and read. I wanted to make a light, which is itself a tool for seeing, out of something that has essentially the same function.”

The contents of the ‘unprepped plastic’ carton, meanwhile, might eventually become another ‘Tide’ chandelier, the type with which he made his name at Designersblock (now part of the London Design Festival) in 2005, constructed from plastic litter he finds on beaches. “I am kind of disgusted by how much there is. But you find such amazing things and think, how did that end up here?” Once he found a pair of false teeth. Plastic ducks and messages in bottles are practically commonplace.

Stuart Haygarth, ‘Tide’, 2018

COURTESY: Stuart Haygarth

In 2012 he walked the coast (“not in one go”) from Gravesend, where the Thames meets the North Sea in Kent, to Land’s End in Cornwall, a distance of nearly 300 miles, sleeping in a campervan, and collecting flotsam and jetsam as he went for a huge installation commissioned by University College London Hospitals for its Macmillan Cancer Centre. “I wanted to create this kind of explosion,” he says. “In the centre [all the objects are] white, then yellow, then orange, so there are all these gradations of colour and darkening to black. There’s no light source in there.” The light that seems to emanate from it is an illusion effected by the care with which he categorised each component and “created by their colours”.

Stuart Haygarth, ‘Tide’, 2018 (detail)

COURTESY: Stuart Haygarth

“I’ve always been practical,” he says. As a child in the small Lancashire town of Clitheroe in the north of England, he made furniture for his sister’s dolls’ house and built “go-karts with pram wheels, metal-and-wood frames and steering mechanisms. That was a big thing when I was young.” His talent for “making things with [his] hands” came from his parents. His father was a builder “who could always fix things”; his mother was a teacher and an accomplished needlewoman and knitter. “She used to make all our clothes. Most parents would buy their children’s school uniform from a particular shop: a manufactured jumper, green with a gold band around the V. But my mum knitted me one. I grew up being totally embarrassed! Though now I think it’s really cool that she used to do that.”

Stuart Haygarth at work on a ‘Flame’ chandelier

COURTESY: Stuart Haygarth / PHOTOGRAPH: Jake Fox

“Haygarth’s ‘Flame’ series of chandeliers are composed of vintage amber glassware – upturned jugs and vases, saucers and bowls …”

Stuart Haygarth at work on a ‘Flame’ chandelier

COURTESY: Stuart Haygarth / PHOTOGRAPH: Jake Fox

“… then threaded on to vertical brass rods so that each strand evokes, he says, ‘the shape of a flickering flame’”

At 18, he left for art school in Exeter – “to get as far away as possible” – where he studied graphic design and photography. Even so, “My work was always three-dimensional. I would build room sets and then photograph them. The camera was just a tool.” Later he pursued a successful career as an illustrator, working for magazines and book publishers, designing jackets for novels by the likes of Isabel Allende and Joanne Harris, the bestseller Chocolat among them. Again, his method was to arrange objects and printed material evocative of the text, “building assemblages, a bit like Joseph Cornell” and photograph them. “So I’d always collected things and had an archive of objects.”

Thus in many ways his shift into design was a natural progression, especially in view of the way colour, light and composition – the essential elements of photography – inform his work.

Lately Haygarth has started to collect nitrous oxide capsules – “probably for a table” – and to work with incandescent bulbs, Victorian hand mirrors and 19th-century magic-lantern slides. “Again, it’s to do with things that have become redundant,” he says. “A lot of my work is about abandonment and loss, I think. And giving things a second life.”

Stuart Haygarth at work on ‘Comet’ chandelier, 2022

COURTESY: Stuart Haygarth / PHOTOGRAPH: Jake Fox