Simone Pheulpin / Plieuse de Temps

Through her fingers, simple cotton fabric undergoes an alchemy … the French textile artist is celebrated with an exhibition to mark her 80th birthday.

Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris

7th December 2021 – 16th January 2022

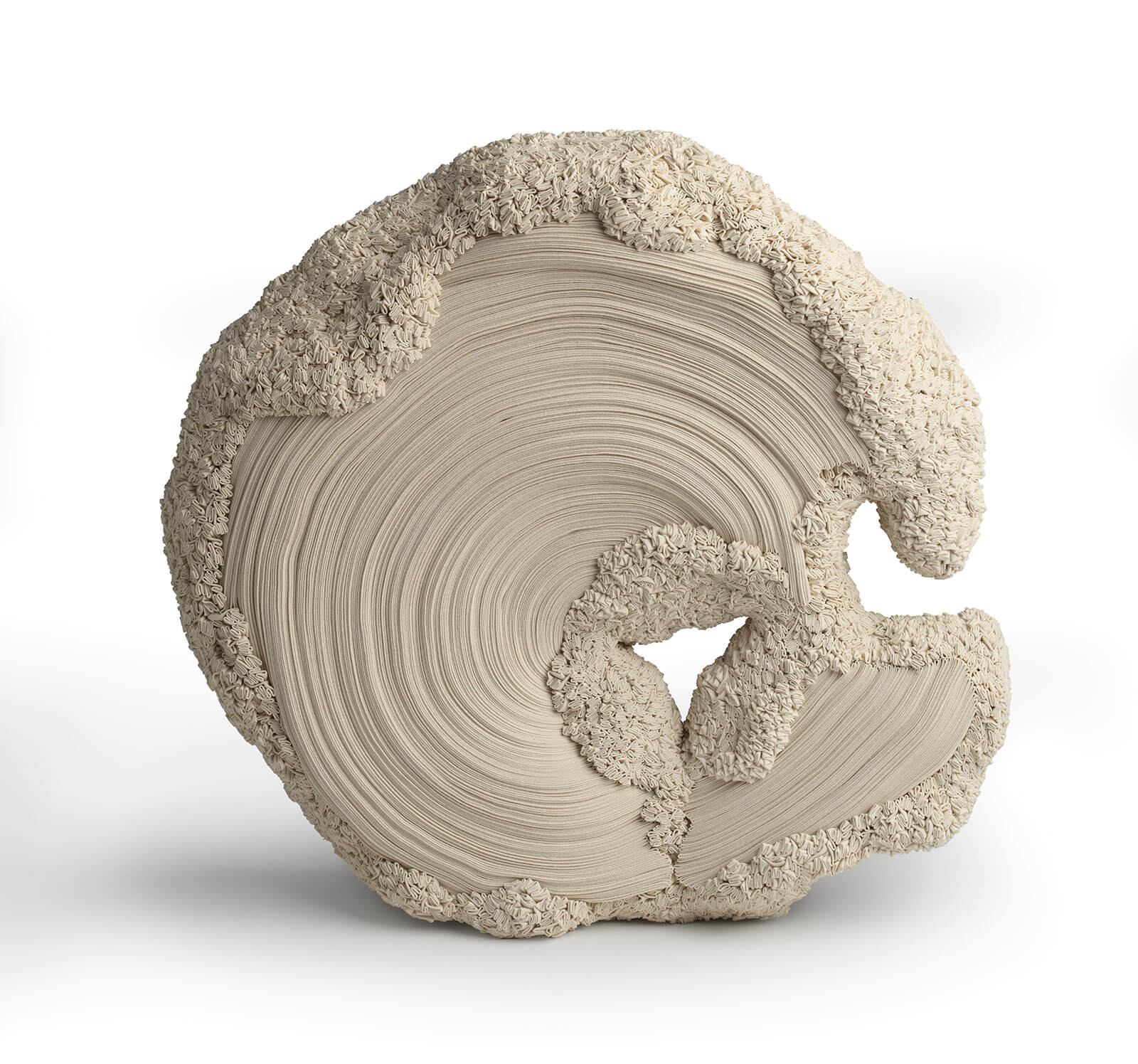

Simone Pheulpin, ‘Ensemble II’, 2006

COURTESY: Simone Pheulpin / PHOTOGRAPH: © Antoine Lippens

“WHEN I STARTED making my fabrics in Nancy, nobody wanted to see them,” Simone Pheulpin, 80, recalls. “In the 1980s, textiles were badly perceived as ‘women’s work’. I could never have imagined being in the Art Nouveau rooms with [cabinet-maker] Louis Majorelle in the Musée des Arts Décoratifs.”

It’s a rainy November afternoon when we meet to discuss Pheulpin’s exhibition, which opened in early December at the MAD in Paris. Nearly four decades after she began making sculptures with humble ivory-coloured raw fabric, Pheulpin, now 80, has been invited to showcase her works in the museum’s hallowed eighteenth century, Art Nouveau and Art Deco rooms in a dialogue with the permanent exhibits.

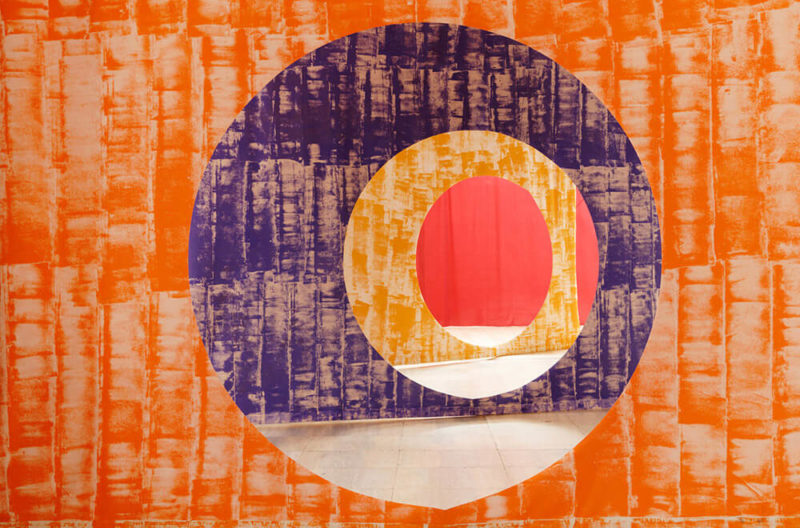

Exhibition view

COURTESY: © MAD, Paris / PHOTOGRAPH: Christophe Dellière

Pheulpin’s material of choice is invariably raw cotton, traditionally used for the lining of curtains and as a support fabric. She buys the monochrome fabric from one of the last French textile factories in the Vosges region in northeastern France, where she grew up and still lives today. In her masterful hands, this ordinary material is transformed into extraordinary feats of imagination.

Simone Pheulpin, ‘Croissance III’, 2015

COURTESY: Simone Pheulpin

By meticulously folding strips of fabric, and attaching pins to the back to keep the folds in place, Pheulpin creates sculptural works that are evocative of timeless landscapes. Rifts and strata bring to mind rocks, cliffs, mountains, scorched earth, fossils and coral. Pheulpin’s output is intrinsically and aesthetically linked to the history and geography of the Vosges, which is characterised by forests and lakes. “I’m inspired by everything that’s natural,” says Pheulpin, who cites the British sculptor and land artist Andy Goldsworthy as an early influence.

Simone Pheulpin, ‘Triptyque’, 2020

COURTESY: Simone Pheulpin / PHOTOGRAPH © Antoine Lippens © Adagp, Paris, 2021

Born in Nancy, Pheulpin hails from the same hometown as the post-war social housing engineer/architect/designer Jean Prouvé. What predisposed Pheulpin’s fascination for pleating material was the childhood experience of accompanying her father to a printer’s shop. “Small strips of paper would fall down from the printing machine and the printer taught me to make an accordion,” Pheulpin recollects. “And the pleating followed the same principle as in my textile works.”

Simone Pheulpin, ‘Croissance III’, 2015 (detail)

COURTESY: Simone Pheulpin / PHOTOGRAPH © Antoine Lippens © Adagp, Paris, 2021

Married to an engineer, Pheulpin started expressing herself creatively by making brightly coloured, decorative panels for her children. She would use the ivory fabric to solidify her compositions. One day, she had an epiphany and felt the urge to start working with it on its own. In the ensuing years, Pheulpin has appropriated this cream fabric, creating shadows and reliefs through its folds, just as the French artist Pierre Soulages has consistently used black acrylic paint to convey light and shadow.

Simone Pheulpin, ‘Jéromine’, 2019

COURTESY: © MAD, Paris / PHOTOGRAPH: Christophe Dellière

Why is she attracted to it? “It’s soft to touch, and calm,” she replies simply. As the strips of fabric would not stay in place, Pheulpin used pins to create her first “paintings”. Self-taught, her desire to create is instinctive. She envisions the piece in her mind and laboriously sets about making it. With fabric laid out on a large table in her living room, alongside boxes of pins, thimbles and scissors, she constructs her pieces with the radio or television switched on – working in an almost trance-like state. “I enter into my own world but it needs to be a noisy, lively ambience,” she says, smiling. “It’s strange, no?”

Simone Pheulpin, ‘Jéromine’, 2019

COURTESY: © MAD, Paris / PHOTOGRAPH: Christophe Dellière

For Pheulpin, the fabric is like a partner that has the upper hand in her creative process. “If the fabric doesn’t want to go in the place that I’d like, I’ll do what it wants,” she laughs. “It’s always the fabric that wins, it’s never me.” Pheulpin creates around 10-12 works a year but, surprisingly, she has kept very few of them. “It’s the moment of creation that matters to me but if somebody who likes it buys it, that’s great,” Pheulpin says.

Simone Pheulpin

COURTESY: Simone Pheulpin / PHOTOGRAPH © Antoine Lippens © Adagp, Paris, 2021

The piece that launched her career is ‘Décade’ (1987), composed of ten identical wall-mounted columns, each with a belly-like protrusion, which was commissioned for the International Tapestry Biennial in Lausanne. It took an entire year to complete. Pheulpin made one column for each month of a pregnancy and then added one extra column to subvert the meaning. Then in 1994, she made ‘Silhouette’, a two-metre-high rock-like formation that was first shown in a church in Troyes. Other commissions have led to her work being exhibited in textile and tapestry events in Kyoto and Poland. “My work was perceived differently in Japan, where people grasped the pleating, and my sculpture was bought immediately,” she says.

Simone Pheulpin, ‘Éclosion Épingles’, 2019

COURTESY: © MAD, Paris / PHOTOGRAPH: Christophe Dellière © Adagp, Paris, 2021

As her works grew increasingly complex and intricate, Pheulpin decided to have some of them X-rayed. The X-rays reveal the vertebra of the pins holding the body of each piece together and the hollowed forms of the fabric. If her gentle creations belie the labour intensiveness involved, the X-rays are a document of her painstaking virtuosity.

Simone Pheulpin, ‘Éclosion Épingles’, 2019

COURTESY: © MAD, Paris / PHOTOGRAPH: Christophe Dellière

In recent years, Pheulpin’s work has gained institutional recognition and entered the collections of the Victoria and Albert Museum and the Art Institute of Chicago. As well as reflecting her perseverance, this attests to how the success of artists such as Anni Albers and Sheila Hicks has helped to shift the perception of fabric-based art and break down prejudice. “It’s really been in the last 15 years that textiles are increasingly present in galleries and interest collectors,” acknowledges Pheulpin, who was nominated for the Loewe Craft Prize at London’s Design Museum in 2018.

Simone Pheulpin, ‘Eclipse VI’, 2012

COURTESY: Simone Pheulpin / PHOTOGRAPH: © Antoine Lippens

Pheulpin’s exhibition at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs arose thanks to curator Cloé Pitiot, who discovered her work on Maison Parisienne’s stand at PAD fair in Paris a few years ago. Pitiot presented it to the museum’s acquisition committee, which led to three pieces joining the museum’s collection.

Exhibition view

COURTESY: © MAD, Paris / PHOTOGRAPH: Christophe Dellière

For the show, Pitiot envisaged creating a pathway by situating 48 of Pheulpin’s creations throughout the period rooms, alongside Majorelle’s inlaid furniture and in Jeanne Lanvin’s dark blue apartment and bathroom. “I was struck by how some of Simone Pheulpin’s works corresponded with the lakes on the chinoiserie panels, and how the coral pieces would look in Jeanne Lanvin’s bathroom,” Pitiot says.

Exhibition view

COURTESY: © MAD, Paris / PHOTOGRAPH: Christophe Dellière

At the age of 80, Pheulpin finds herself busier than ever and shows no intention of slowing down. “I’ve never worked as much as during the lockdowns,” she exclaims. “Luckily, I had all the needles and fabrics that I needed and could take on large commissions.”

The sense of tranquillity that emanates from Pheulpin’s contemplative works resonates with how many of us have been seeking peace and calm during the pandemic. While there is no political message about climate change within her work, there is a softer intent. “What I want to transmit is something that makes people feel good and serene and gives them a breath of oxygen so that their mind wanders,” Pheulpin says dreamily.