Blanc de Chine, A Continuous Conversation

Contemporary white porcelain sculptures are juxtaposed with historic pieces, providing an exquisite showcase of skill and artistry.

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

5th September 2019 – 10th May 2020

Blanc de Chine

Peter Ting at work

VIDEOGRAPHY: Calvin Sit COURTESY: Ting-Ying Gallery

MY FIRST QUESTION to ceramic designer Peter Ting about his gallery’s contribution to the Victoria and Albert Museum’s new show ‘Blanc de Chine, a Continuous Conversation’, is why we should still be talking about this particular Chinese porcelain. In response, the co-founder of Ting-Ying Gallery tells me about the history of Dehua’s pure white clay. “It was the first white porcelain to come to Europe, arriving with Marco Polo in 1295,” he explains, “and it was also the white porcelain that inspired Meissen, Europe’s first porcelain manufactory. It’s where European porcelain began.”

Figure of Guanyin

COURTESY: ©Victoria and Albert Museum, London

He also tells me how Beijing’s contemporary silk road initiative ‘One Belt, One Road’ echoes the export of Blanc de Chine in the early 18th century, when serene Buddha figures with their distinctive cast down eyes and folded garments were wrapped in straw and carried down from the Dehua mountains and shipped west across the sea. These are all compelling explanations of course (and the show’s curator Xiaoxin Li explores the history in some depth in an accompanying satellite exhibition in the museum’s China galleries), but then Ting pauses and says, “but the bottom line is because it is exquisite. This show is a celebration of beauty.”

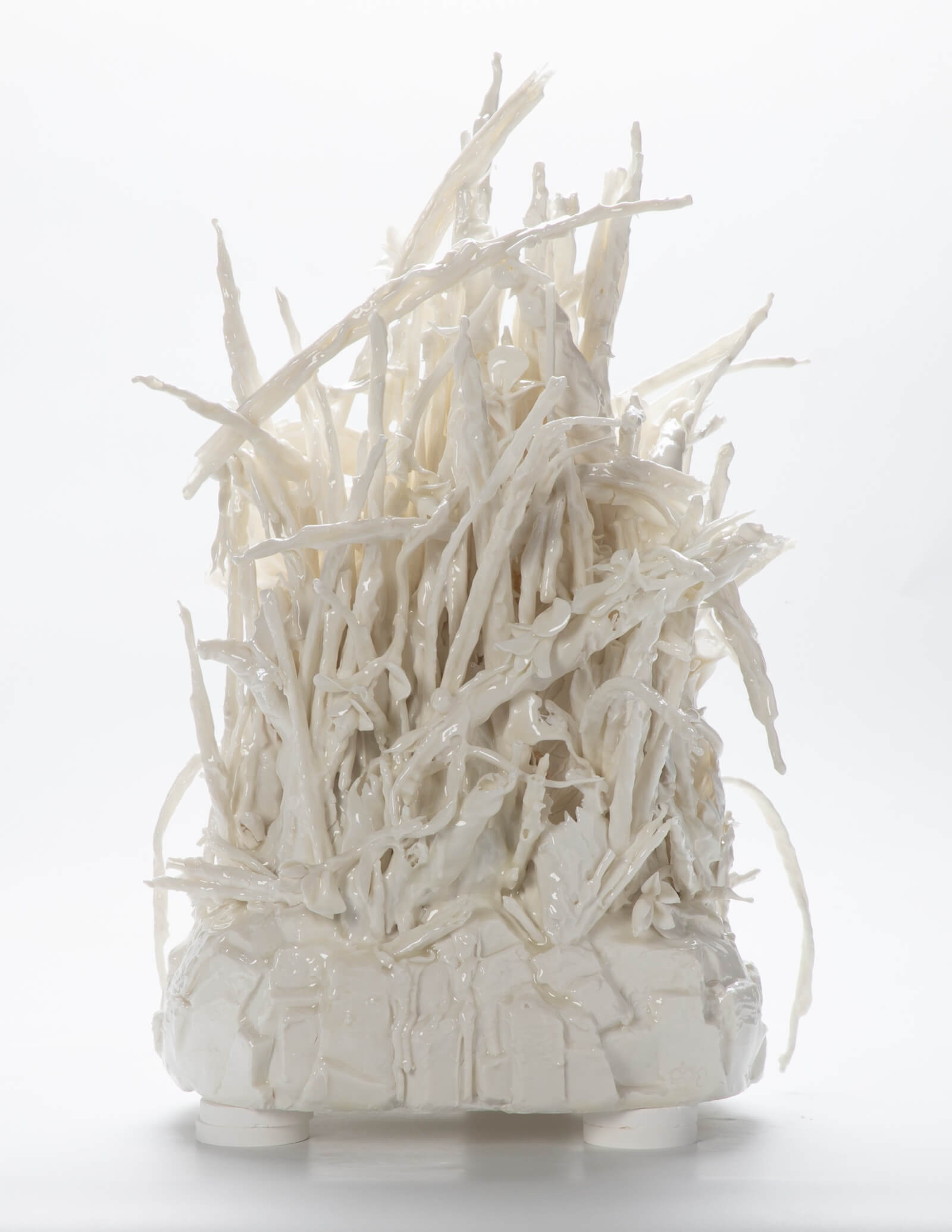

Peter Ting, ‘Flower wreath’, 2019

COURTESY: ©Ting-Ying Gallery

Xiaoxin has set historic examples – some of which date back to the very first examples created during the Ming dynasty (1368-1644) – against pieces made by Ting and five other contemporary artists, as a way of demonstrating the versatility of the material. “When people talk about Blanc de Chine, they tend to think of the sophisticated Buddha figures,” she explains, “but the Dehua potters made the very best white porcelain so there is also much, much more. In his book The Dehua Potters, John Ayers described them as being ‘so creative they didn’t only make the sublime, they made the ridiculous’, and that’s what I wanted to demonstrate with this exhibition. We have such a variety of different styles here, from Jeffry Mitchell’s joyous, vital work to Lucille Lewin’s exquisitely poetic pieces, which together reveal the many different faces of this extraordinary clay.”

Jeffry Mitchell, ‘Vase’, 2019

COURTESY: ©Ting-Ying Gallery

Beauty isn’t a very fashionable word in art and design circles so Ting’s descriptor is a brave one, but any other would sell this show short. This conversation between old and new not only shines a new light on a fascinating history, it lifts the soul.

Liang Wanying, ‘Mall Man’, 2018

COURTESY: ©Paul Nobel

The six contemporary ceramicists:

Peter Ting

Ting’s three works – ‘Cup & Saucer’, ‘Flower Wreath’ and ‘Pearl Vase’, share a case with a late 16th/early 17th century ‘Figure of Guanyin’ by He Chaozong. “It’s like being paired with Da Vinci,” he says. “Chaozong gave Dehua its DNA and this piece, with its exquisite, compassionate face, soft drapery and fine decorative details has everything.” Ting has responded directly to those details; delicate, luminous white fingers surround the saucer, tiny pearls (made by rolling several balls of Blanc de Chine clay against each other) cluster around the vase, wafer thin flowers spill over the sides of a perfectly round container. “This clay is plastic,” he says. “When you roll it and curl it, it doesn’t crack so you can do extraordinary things with it.”

Peter Ting, ‘Pearl Vase’, 2019

COURTESY: ©Ting-Ying Gallery

Su Xianzhong

The fourth generation of Dehua’s renowned Yun Yu Porcelain studio, Su makes sculptures that challenge the tradition he has grown up with. ‘Landscape 2018’, is an abstract, fluid iteration of his great-great grandfather’s ‘Figure of Luohan’ (which is shown alongside it), while the curling wisps of piled ‘paper’ titled ‘Medium Paper Nos. 10 & 11’ honour the unique qualities of this material in an utterly contemporary way.

Su Xianzhong, ‘Landscape’, 2018

COURTESY: ©Su Xianzhong

Su Xianzhong, ‘Medium Paper No 2 and No 3’, 2019

COURTESY: ©Ting-Ying Gallery

Jeffry Mitchell

American folk artist Jeffry Mitchell’s almost-kitsch works seem far removed from the elegant delicacy of traditional Blanc de Chine, but look closely and you can see that every detail, from the Foo dogs to the petals of plum blossom, has a direct connection to its history, creating a link not only between past and present – but also between West and East.

Jeffry Mitchell, ‘Plum tree’, 2019

COURTESY: ©Su Xianzhong

Liang Wanying

As a Chinese artist living in America, Liang has as uniquely innovative perspective of Blanc de Chine. Interested in the formality, structure and ritual of Chinese tradition, the three whiter than white installations she is showing here cause the viewer to reflect on ideas of purity.

Liang Wanying in her studio

COURTESY: ©Liang Wanying

Babs Haenen

Blanc de Chine is malleable and comes in many shades of white. Dutch ceramicist Babs Haenen’s series of three ‘Turbulent Vessels’ responds to both these qualities – the creased and crumpled surface an embracing of the pliability of the clay and the blueish-white tint a reference to Qingbai glaze (which was produced in Dehua in the Song dynasty and is believed to have been used on the vase Marco Polo brought to Europe in the 13th century).

Babs Haenen, Turbulent Vessel’, 2019

COURTESY: ©Babs Haenen

Lucille Lewin

Lucille Lewin’s interlinked, circular series ‘The Secret Life of a Pea’ is “very much Blanc de Chine,” she says. “It is about the material and what you can do with it – European porcelain is dry and brittle and cracks easily, but this is like plastic. You can make it very thin and when you touch it together, it sticks so you can achieve such lightness and freshness. There is also a wonderful tradition of storytelling and celebrating nature in Blanc de Chine, and this work is also about the natural world and fragility colliding with chaos and climate change.”

Lucille Lewin, ‘The Secret Life of the Pea’, 2019

COURTESY: ©Ting-Ying Gallery

Blanc de Chine, a Continuous Conversation – featuring historic and contemporary ‘Blanc de Chine’, white porcelains made in Dehua, China.