South Korean Design

A heritage of serious craftsmanship, combined with a cultural renaissance, is creative fuel to a new generation of artist-makers.

Lee Hun Chung, ‘Day Bed’, 2019

COURTESY: Messums Wiltshire

“IT’S NOT OFTEN you see someone throw a sofa,” remarks Paul Greenhalgh at the opening of Korean Ceramics, a joint show he has curated of works by Ree Soo-Jong and Lee Hun Chung, which recently transferred from Messums’ London gallery to its 13th century Wiltshire barn. A generation apart – Lee was a pupil of Ree’s for a time – these two internationally renowned contemporary artists both came to ceramics mid-career and both exemplify the idiosyncratic creative sensibility that is fuelling South Korea’s extraordinary cultural boom.

Ree Soo-Jong, ‘Moon Jar’, 2019

COURTESY: Messums Wiltshire

With museums opening at a rate of knots (183 predicted to launch by 2023), K-pop launched as a global phenomenon, director Bong Joon-ho’s coruscating social satire Parasite becoming the first non-English-language nominee to win best picture at the Oscars, not to mention the success of Cho Nam-Jo’s ground-breaking feminist novel Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982 (translated into 18 languages), South Korea is simultaneously celebrating its history and leading the world in cultural and technological innovation.

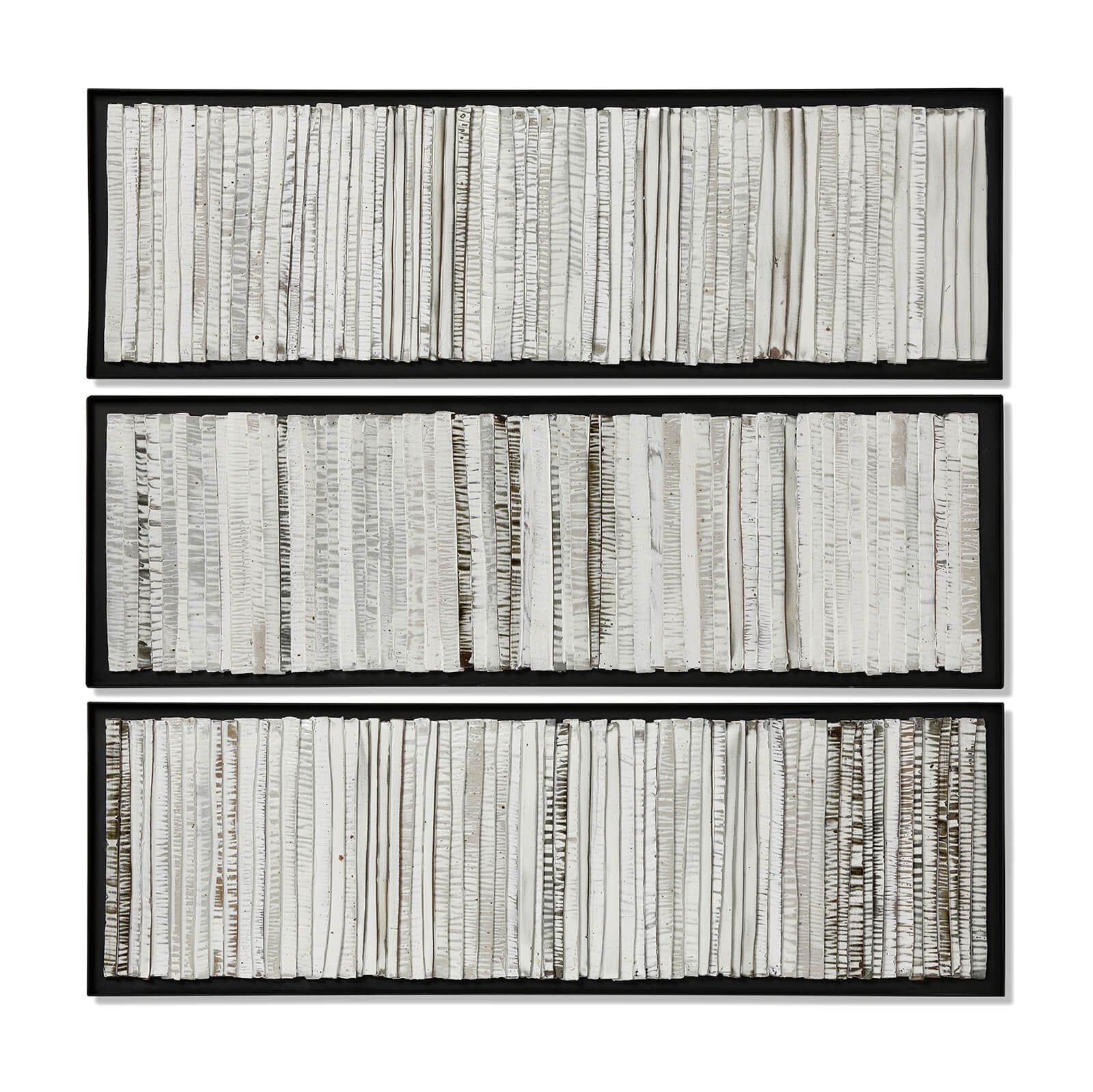

Park Sung Wook, ‘Pyeon White Forest’ (trio), 2017

COURTESY: Lloyd Choi Gallery

“The Oscars came as no surprise to the Koreans,” says Greenhalgh, a writer, curator and art historian who is Director of the Sainsbury Centre at the University of East Anglia. “They have dominated east Asian films for decades and now dominate TV, music, fashion and the visual arts. Ceramic is a major art form in Korea, unrivalled at various points in history – the porcelain vases of the Middle Chosun Dynasty are among the greatest achievements of world art – and it is entering a new golden age.”

Choi Bo-Ram, ‘Blue Jar’, 2017

COURTESY: Lloyd Choi Gallery

Ree and Lee make complex works that are characterised by a fusion of the traditional and the contemporary, involving the deft cross-fertilisation of disciplines and revealing a rich vein of humanity juxtaposed with subversive humour, all supported by virtuoso technique. Precisely the properties that inform Bong’s uproariously dark exposé of inequality in South Korea. Defying categorisation, Parasite is a genre mash-up, full of local detail while referencing western directors from Hitchcock to Tarantino, layering comedy, horror, violence, sex and social commentary in a way that is ‘very Korean,’ says artist/designer Kim Hoon-Joo, who co-curated Korean Ceramics with Greenhalgh.

“I think we lost our identity,” Hoon-Joo explains, referring to Korea’s recent traumatic history of Japanese colonisation (1910-1945), followed by US and Soviet occupation, the Korean War with its subsequent division of the country into north and south, the separation of many families, and then military dictatorship in the south before autocracy was replaced in 1997 with a modern democracy. “We are finding ourselves again through ceramics and the arts.”

Kwak Hye Young, ‘Seeing the Sound of Rain’, 2019

COURTESY: Lloyd Choi Gallery / PHOTOGRAPH: Moon Ray Studio

Kim describes a new confidence that has been building since the 1988 Seoul Olympics when South Koreans were suddenly given passports. “Back-packing became the cool thing to do. We began to study abroad, and our exposure to western art led us to think about our own culture. We are now reimagining what it means to be Korean, approaching old techniques in a completely modern way.”

Yun Ju Cheol, ‘Cheom-jang’ vessel, 2014

COURTESY: Lloyd Choi Gallery / PHOTOGRAPH: Yun Ju Cheol

Ree Soo-Jong’s signature piece in Korean Ceramics is a tall, white vessel with a single, black, gestural brush mark across its face, “a spectacular, existential statement about past and present,” says Greenhalgh. Long recognised as one of Korea’s principle ceramic artists, Ree makes his moon jars in the traditional way, by joining two thrown bowls to create a spherical form, but he flouts convention by leaving the join exposed instead of smoothing it over to hide the process, and adds lines, drips, dabs and splashes of paint to their surfaces. This union of form with the painted surface points to “a sublime level of confidence”, says Greenhalgh. “It’s incredibly difficult to put a black mark on a pot without it running in the kiln. Ree’s statement moon jar is a piece of bravura, simple but extremely complicated.”

Ree Soo-Jong, ‘Moon Jar with Iron-Oxide’, 2015

COURTESY: Lloyd Choi Gallery / PHOTOGRAPH: Ye Studio

Lee, who got his MFA in sculpture at San Francisco Art Institute and is a conceptualist known for his large scale installations, has made a range of furniture in modelled and thrown ceramic – and cement. A witty play on the Korean principle that ceramics must have a function, Lee’s sofas, daybeds, tables, stools and pots are glazed in a palette of turquoise, white and an oxidised bronze that coats these everyday, domestic items with an ancient patina. The absurdist element of this collection is embodied by a planter shaped like an enormous head, with clownish ears and painted facial features, sprouting lush foliage as hair. Lee is serious too: “He’s an expressionist,” says Greenhalgh, “bringing together different emotional impulses.”

Lee Hun Chung, ‘Macaroon Stool’, 2016

COURTESY: Messums Wiltshire

Korean contemporary ceramics are full of thought and emotion but – in direct opposition to western conceptualism where ideas themselves can become the material – Korean makers express themselves through working the clay with their hands. “Ree believes that a day’s physical labour is far more honest than ten seemingly good concepts,” says Greenhalgh, “though he is acutely aware of global developments in artistic practice and the ideas that underpin them. Lee too thinks that the role of the individual artist is to expose ideas through materials. This sense of artisanship seems to be very much part of the Korean attitude to culture.”

Ree Soo-Jong in the studio

COURTESY: Messums Wiltshire

So-yeong Chung, director of Gallery Wannmul, one of four South Korean galleries to exhibit at London’s international craft and design fair, COLLECT 2020, agrees. Showing me round her booth last month, she told me that “as a gallery, we are very focused on materials and we admire artists using traditional techniques. The deep knowledge a master has of his materials, and the skills he develops in his methods and practice, means he can experiment.”

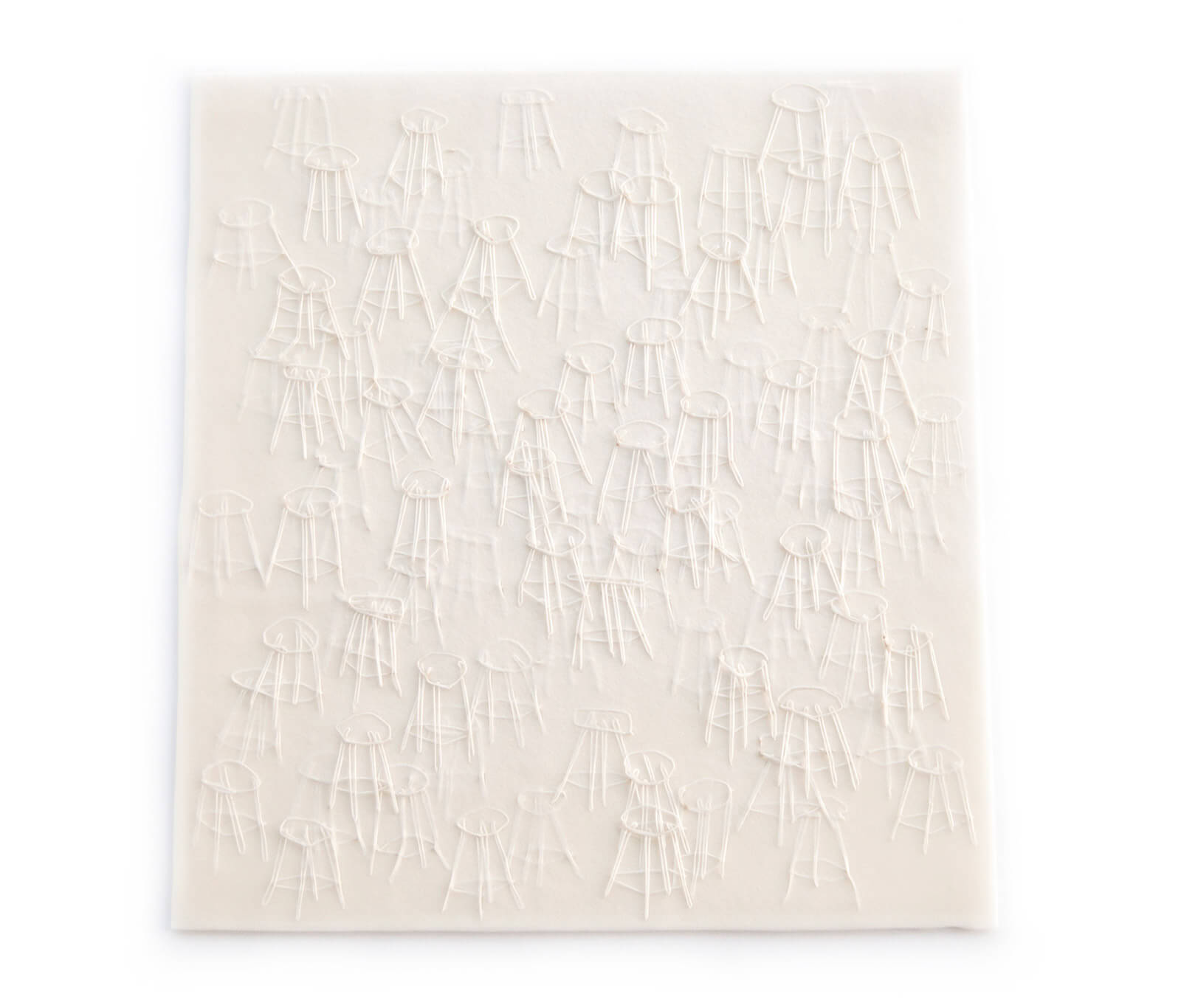

The term master craftsman, used by Koreans as a mark of the highest respect, sounds patriarchal but this is no longer the case, adds Chung. The majority of artists on her stand were women, including Su-yeon Kim, whose glass panels on which she draws are purely aesthetic, with no practical function. Their artistic merit comes from “her meticulous treatment of the material,” says Chung. “Korean audiences can be ruthless, calling such work ‘purposeless’ and ‘pointless art’, but this is wrong.”

Su-yeon Kim, ‘Forest of the stools: white 02’, 2019

COURTESY: gallery WANNMUL

Lloyd Choi, who launched her eponymous gallery at COLLECT 2020, having been a curator at the Korean Craft and Design Foundation for seven years, says that a new generation of artists does not feel the pressure to make practical works and is instead, creating “fascinating, conceptual ceramics.” But she concedes that there is still much debate in Korea and the market, for now, is mainly in the west.

Yun Ju Cheol, ‘Cheomjang’ Moon Jars, 2018

COURTESY: Lloyd Choi Gallery / PHOTOGRAPH: Young-in Myoung

Her inclusion of one of Ree Soo-Jong’s moon jars on her stand, suggests that his work is not just a mark of quality but provides useful context for a young gallery with a point to prove. “Yes, Ree’s moon jars are totally conceptual,” she says, “and he had the confidence to re-tell that story, to push boundaries, decades ago.” Ree was the father of Do-jo, which means ‘ceramic sculpture,’ a radical movement in the 80s that merged ceramics and fine art, but then disappeared. “People went back to wanting cups in the 90s,” says Choi, “so I decided that my mission was to introduce young, conceptual Korean makers to London. I am showing Ree with five artists whose practices embody the spirit of Do-jo.”

Lloyd Choi with ‘Seeing the Sound of Rain’ and ‘Blue Jar’ (in process)

COURTESY: Moon Ray Studio

“I decided that my mission was to introduce young, conceptual Korean makers to London.”

Choi Bo-Ram, ‘Blue Jar’, 2017

COURTESY: Lloyd Choi Gallery / PHOTOGRAPH: Moon Ray Studio

“I am showing Ree Soo-Jong with five artists whose practices embody the spirit of Do-jo.”

THE EXCELLENCE AND ambition of this young generation is reflected in the the short list for this year’s prestigious Loewe Foundation Craft Prize. Six of the thirty finalists are Korean and expert panel member Hyeyoung Cho suggests that this is due to a change in the country’s social structure, partly stimulated by the internet – South Korea has the fastest internet in the world – and access to an abundance of information. “In Confucian practice, Koreans have always been taught to respect the older generation but over the past decade there has been a flood of individuals determined to be acknowledged for themselves, not as acolytes of famous makers. They are finding new ways of doing things.”

Sungyoul Park, ‘Inborn’, 2019 (lacquer artist and one of the finalists of the Loewe Foundation Craft Prize 2020)

COURTESY: Loewe Foundation

Having said that, Korea’s rich history and traditions certainly have had a hand in their success, says Cho. Two of the Koreans on the list work with lacquer which, she says, is “extremely difficult to master. To see Sukkeun Kang and Sungyoul Park push this material to its limits is very exciting.” Lacquer, or ottchil, is not taught at university so young practitioners have to learn from master craftsmen.

Sukkeun Kang, ‘For: Ottchil Wooden Bowl’, 2019 (lacquer artist and one of the finalists of the Loewe Foundation Craft Prize 2020)

COURTESY: Loewe Foundation

Paul Greenhalgh, who has visited South Korea many times, confirms that the scene there is “very international but they are also deeply tied to their heritage.” Part of this inheritance, is the high regard in which ceramics, alongside other crafts, are held.

Park Sung-Wook, ‘Buncheong Blue Bottles’, 2020

COURTESY: Lloyd Choi Gallery / PHOTOGRAPH: Park Sung-Wook

“The National Museum in Seoul has breathtaking ceramics, and the Samsung Museum has floors of international contemporary art and floors of Korean ceramics, all given the same artistic value. The Gyeonggi International Biennale is the most important ceramic biennale in the world and it takes place outside Seoul in the middle of a ceramic theme park! I wish we had one of those. It’s hugely popular – thousands of families go and are given big lumps of clay to work. They even have a Celadon theme park with a working 12th century kiln,” he adds, longingly.

Probably the most fashionable event is Seoul’s 17-year-old Craft Trend Fair, held in December, Huunjoo Kim tells me. “It’s very high status. People queue round the block to get in and that’s happened over the last three years.” Kim thinks this is because people are bored by mass-production and hanker after handmade, handcrafted objects. Greenhalgh concurs but says the main reason is “there’s none of that art/craft/design nonsense. For Koreans, it’s all art, it’s all about making poetry, and that’s the end of that.”

Ree Soo-Jong, ‘Moon Jar’, 2012

COURTESY: Messums Wiltshire

Korean Ceramics was planned to be shown at Messums Wiltshire (21st March – 11th April 2020).

Lloyd Choi Gallery – a contemporary Korean art and design gallery specialised in Korean contemporary studio ceramic.

Gallery Sklo – the first and only art gallery specialising in contemporary glass sculptures and objects in Korea.

LOEWE FOUNDATION Craft Prize 2020 – recognises the shortlisted artists as having made fundamentally important contributions to the development of contemporary craft.