Ettore Sottsass / The Magical Object

Totems, typewriters and utopian ideals, all filtered through oriental philosophy - the fascinating world of the founder of the Memphis movement.

Centre Pompidou, Paris

Until 3rd January 2022

Ettore Sottsass, ‘Maquette spatiale’, 1946-1947

COURTESY: © Adagp, Paris 2021 © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI/Georges Meguerditchian/Dist. RMN-GP

THE ITALIAN ARCHITECT and designer Ettore Sottsass (1917-2007) is renowned for being the founder of the Memphis movement in Milan in 1981. But as the Centre Pompidou‘s new exhibition explores, by the time Sottsass launched the “anti-design” collective that further cemented his avant-garde reputation for postmodern furniture and lighting, he had four decades of creativity under his belt.

Ettore Sottsass, ‘Beverly’, 1981

COURTESY: © Adagp, Paris 2021 © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI/Service de la documentation photographique du MNAM/Dist. RMN-GP

Illuminating the extent of Sottsass’s legacy, it takes us from his early passion for Modernist painting through to ceramic sculptures and ephemeral installations in nature. What emerges is how Sottsass had an avid curiosity for travel and other cultures, in particular the rich colours he observed in India. This led him to create “magical design” and objects having a “ritual and symbolic presence”, according to the Centre Pompidou’s president, Laurent Le Bon.

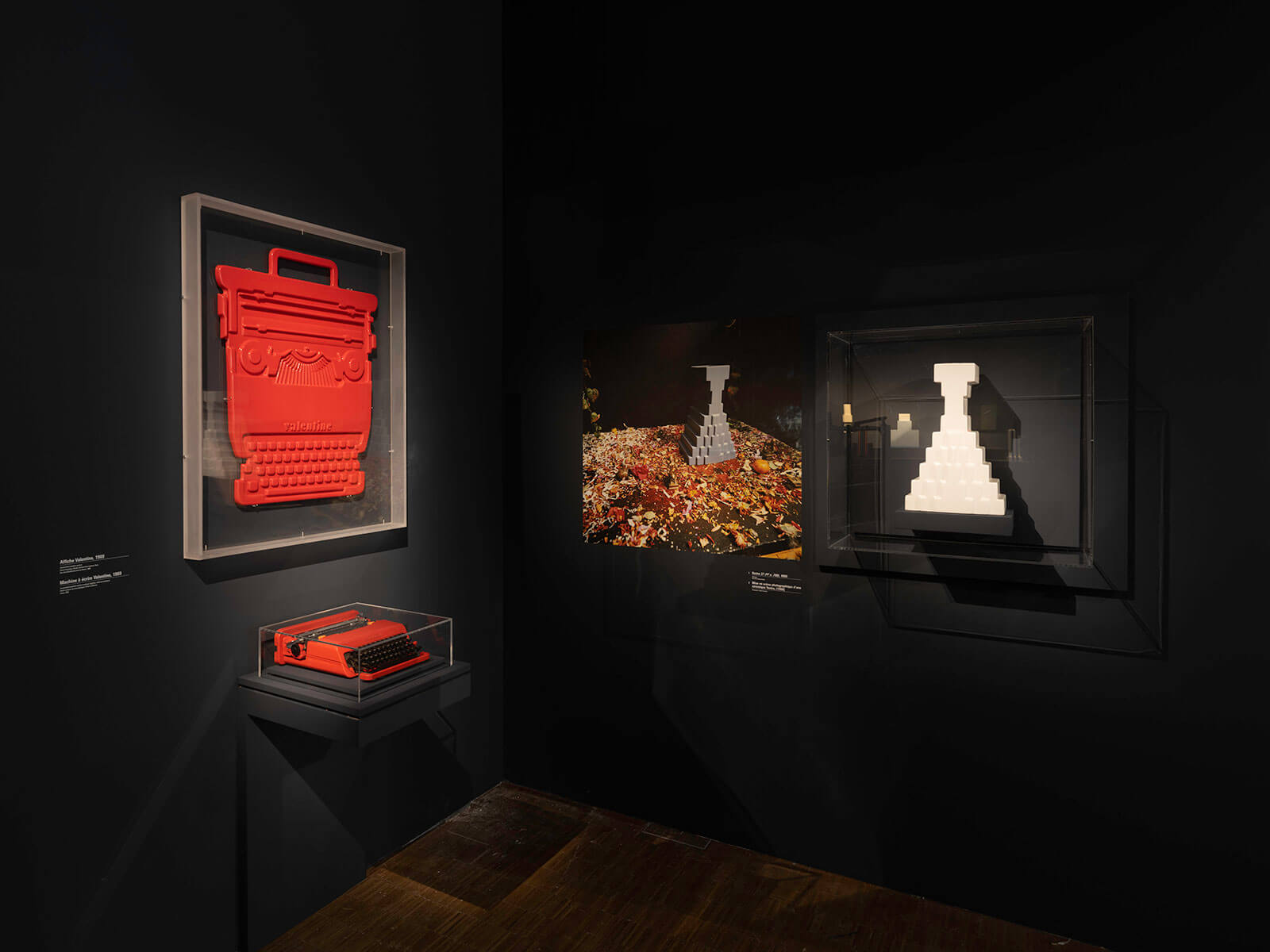

Installation view

COURTESY: Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI / PHOTOGRAPH: Audrey Laurans

France’s institutions have a longstanding relationship with the work of Sottsass. In 1976, the Centre de création industrielle, the precursor to the Centre Pompidou, organised an exhibition at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs. In 1994, the Centre Pompidou held a retrospective. And in 2013 Barbara Sottsass (born Radice), Sottsass’s widow, who was an author and critic, donated hundreds of objects and drawings from his archive to the Centre Pompidou’s Kandinsky library.

Born in Innsbruck, Austria, Ettore Sottsass Jr. was the son of architect Ettore Sottsass Sr. and moved to Turin with his family as a child. After studying architecture, serving in the military during the Second World War and rebuilding war-damaged buildings with his father, he moved to Milan and set up his architecture and design studio in 1947. Early abstract drawings and paintings in bright colours and bold lines were inspired by Kandinsky and were sometimes studies for his sculpture. His multidisciplinary ideas quickly bled into each other: a turquoise ‘Cabinet’ (1948-1949) constructed from multiple rectangular parts in lacquered wood and brass is a marvellous piece of micro-architecture. Black-and-white photos of his apartment and perspectives of his studio further show how he used furniture to structure interiors and saw the interconnection between objects.

Ettore Sottsass, ‘Cabinet’, 1948-1949

COURTESY: © Adagp, Paris 2021 © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI/Philippe Migeat/Dist. RMN-GP

Sottsass’s decision to focus more on design than architecture was pragmatic in the post-war period. “Through design, he could experiment in a way that perhaps he couldn’t do in architecture because it was very difficult to build after the war and design offered another alternative,” Marie-Ange Brayer, the exhibition’s curator, says. “Design for him wasn’t about functionality, but about expressing his way of seeing the world.”

Installation view

COURTESY: Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI / PHOTOGRAPH: Audrey Laurans

In the 1950s, the designer’s all-encompassing vision for the home led him to create mirrors and other objects composed from several wooden elements, as well as textiles and rugs with decorative motifs. He became artistic consultant for the furniture company Poltronova and, a decade later, designed the red Valentine typewriter for the electronics corporation Olivetti. His versatility extended to creating jewellery with geometric shapes, which Sottsass perceived as “miniature architecture”, for his first wife Fernanda, co-editing the first issue of the counterculture magazine Pianeta Fresco and later publishing Casabella, and making ceramics.

Ettore Sottsass, ‘Plate’, 1959

COURTESY: © Adagp, Paris 2021 © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI/Jacques Faujour/Dist. RMN-GP

Sottsass first developed a pop aesthetic in the journal that he kept whilst hospitalised in California (the dry air was believed to have health benefits) after contracting an illness during a trip to India. Following his ‘Ceramics of Darkness’ series reflecting on his illness, Sottsass made brightly striped, joyous totemic ceramics. Composed of stacked elements and fusing influences from the columns in Indian temples and Pop Art, they were exhibited at Galleria Sperone in Milan. Meeting the Beat Generation writers, like Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg, also contributed to his free-spirited ideas.

Installation view

COURTESY: Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI / PHOTOGRAPH: Audrey Laurans

How Sottsass conceived ceramics as being related to the cosmos and the sacred came to the fore in his exhibition ‘Landscape for a new planet’ (1969) in Stockholm’s National museum. Sottsass created vast sculptures from multiple rounded forms, such as ‘Great Altar’ (1969) a spatial arrangement of dark red cylinders, and ‘Pillar’ (1969), comprising dark blue totems. These splendid non-functional pieces evoking a sense of communal living are among the highlights of the Centre Pompidou show. They attest to Sottsass’s talent for sculpture and how it expressed his way of seeing the world.

Ettore Sottsass, ‘Grand Altare’, 1969

COURTESY: © Ådagp, Paris 2021 / PHOTOGRAPH: Erik and Petra Hesmerg/Courtesy The Gallery Mourmans

In many ways, Sottsass was a radical futurologist. For the exhibition ‘Italy: The New Domestic Landscape – Achievements and Problems of Italian Design’ at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1972, Sottsass realised modules for living in tall, grey containers including a shower, a loo and a stove. These futuristic prototypes, like those by his contemporary Joe Colombo, were made years before today’s modular and micro-living societal trend – but never went into production.

Ettore Sottsass, ‘Closet (Toilettes)’, 1972

COURTESY: © Adagp, Paris 2021 © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI/Jacques Faujour/Dist. RMN-GP

In the 1970s, Sottsass interrogated the primordial meaning of construction from an anthropological perspective. On his various travels, he created metaphorical installations from diverse objects. He used stacked boxes to form a flight of stairs in front of a boulder, and poles to form an archway. Sottsass documented these experiments in black-and-white photographs that are shown alongside a projection of coloured photographs from his numerous travels.

Ettore Sottsass, ‘Armoire Superbox’, 1966

COURTESY: © Adagp, Paris 2021 © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI/Jean-Claude Planchet/Dist. RMN-GP

What’s fascinating is how his ‘Superbox’ furniture, made from wood and laminated plastic in striped, striking colours for Poltronova in 1966, foreshadowed Memphis. Displayed in a vitrine at the Centre Pompidou, each architectonic ‘Superbox’ – such as a wardrobe or cabinet – was like an abstraction of its function. They were inspired by his trip to India. “Sottsass discovered through oriental philosophy another way of approaching objects in a sensorial dimension through colour and materials that was a revelation for him,” Brayer says.

Installation view

COURTESY: Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI / PHOTOGRAPH: Audrey Laurans

Through the Memphis movement, which was active in the 1980s, Sottsass elaborated on the aesthetic ideas and materials from the ‘Superbox’ furniture. Indeed, the exhibition ends with Sottsass’s Memphis works in a riot of shapes and colours. On view are his famous ‘Carlton’ bookcase with its multicoloured, zigzagging shelves, and the pink, yellow and red ‘Tahiti’ lamp, among other works. On first impression, they resonate less with the ‘magical object’ theme of the exhibition. Yet it’s apparent that Sottsass’s journeying in a spiritual, searching way through continents and cultures, exploring the link between humankind and objects, culminated in assimilating these multifarious interests into Memphis.