British Ceramics Biennial 2021

Ten years on, the festival of contemporary ceramics has grown in scope and strength.

Stoke-on-Trent

11th September – 17th October 2021

Connor Coulston, ‘Masc 4 Masc’ Toby Jug, 2021

COURTESY: Connor Coulston & British Ceramics Biennial

THE BRITISH CERAMICS Biennial got off to a slow start when it launched in 2009. Back then it comprised a series of small installations spread across venues in the six towns. None of the shows were large enough to hold visitors’ attention and journey times between each site (particularly if you were on foot) were long, with routes occasionally genuinely arduous. I remember taking the train back to London that first year, not expecting to see another edition.

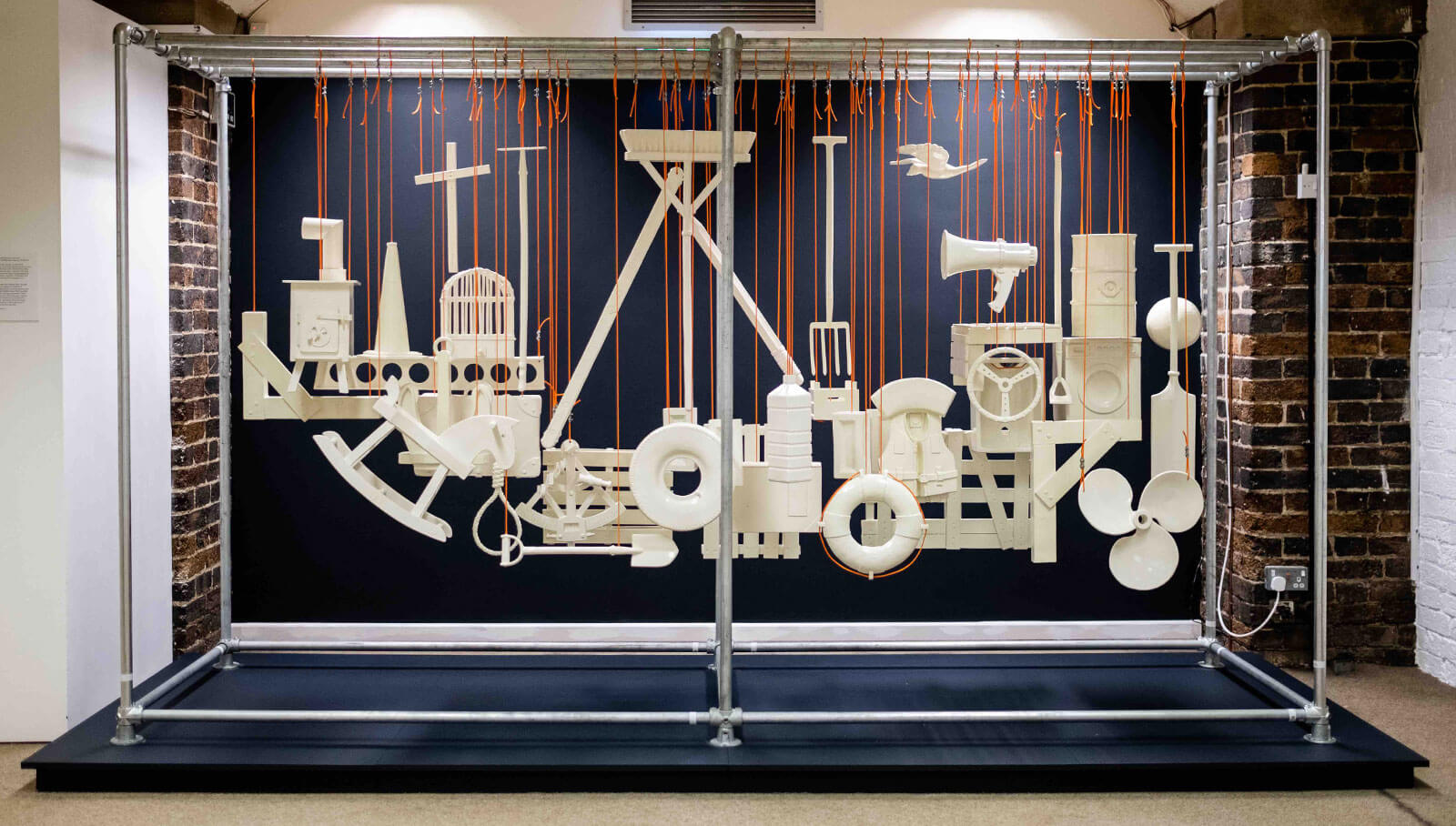

Stephen Dixon, ‘Transient The Ship of Dreams and Nightmares’, 2021

COURTESY: Stephen Dixon & British Ceramics Biennial / PHOTOGRAPH: Jenny Harper

That it’s still here over a decade later is testament to the organisers’ response to the criticisms of that initial year. Jeremy Theophilus and Barney Hare Duke wisely decided to shift much of the festival’s existing activity under a single roof at the China Halls in the magnificent former Spode factory, a ten-acre site notable for its vaulted roof. Suddenly there was a sense of mass and the whole thing worked a treat.

Spode Works site at the original Spode factory

COURTESY: British Ceramics Biennial / PHOTOGRAPH: Instruct

For 2021 things are a little different. The Biennial has a new artistic director and CEO, Clare Wood, for a start – though I suspect she hasn’t been in the job long enough to impose many of her ideas yet. And it is being held in a new venue. Due to structural issues, the Spode building is currently out of bounds, so the festival has moved to The Goods Yard, a 19th century warehouse that was converted into office buildings, near the main railway station.

Laura Plant, ‘Group of 3’, 2021

COURTESY: Laura Plant & British Ceramics Biennial

Has the change of site affected the show? Not really. Its bones remain in place. There’s the headline exhibition ‘AWARD’, for instance, which acts as a snapshot of the British contemporary ceramics scene.

Tamsin van Essen, ‘Porcelain Throwing Knifes’, 2021

COURTESY: Tamsin van Essen & British Ceramics Biennial / PHOTOGRAPH: Matthew Booth

The ten selected artists prove to be an eclectic bunch, ranging from the mosaic figures of Cleo Mussi that chart the history of the British landscape, to the kitsch (though, it transpires, deeply personal) work of Connor Coulston, which, among other things, attempts to discover why Harry Styles stubbornly refuses to fall in love with him, via Stephen Dixon’s meditation on migration.

Cleo Mussi, ‘Man of the Woods and The Burryman’, 2019

COURTESY: Cleo Mussi & British Ceramics Biennial

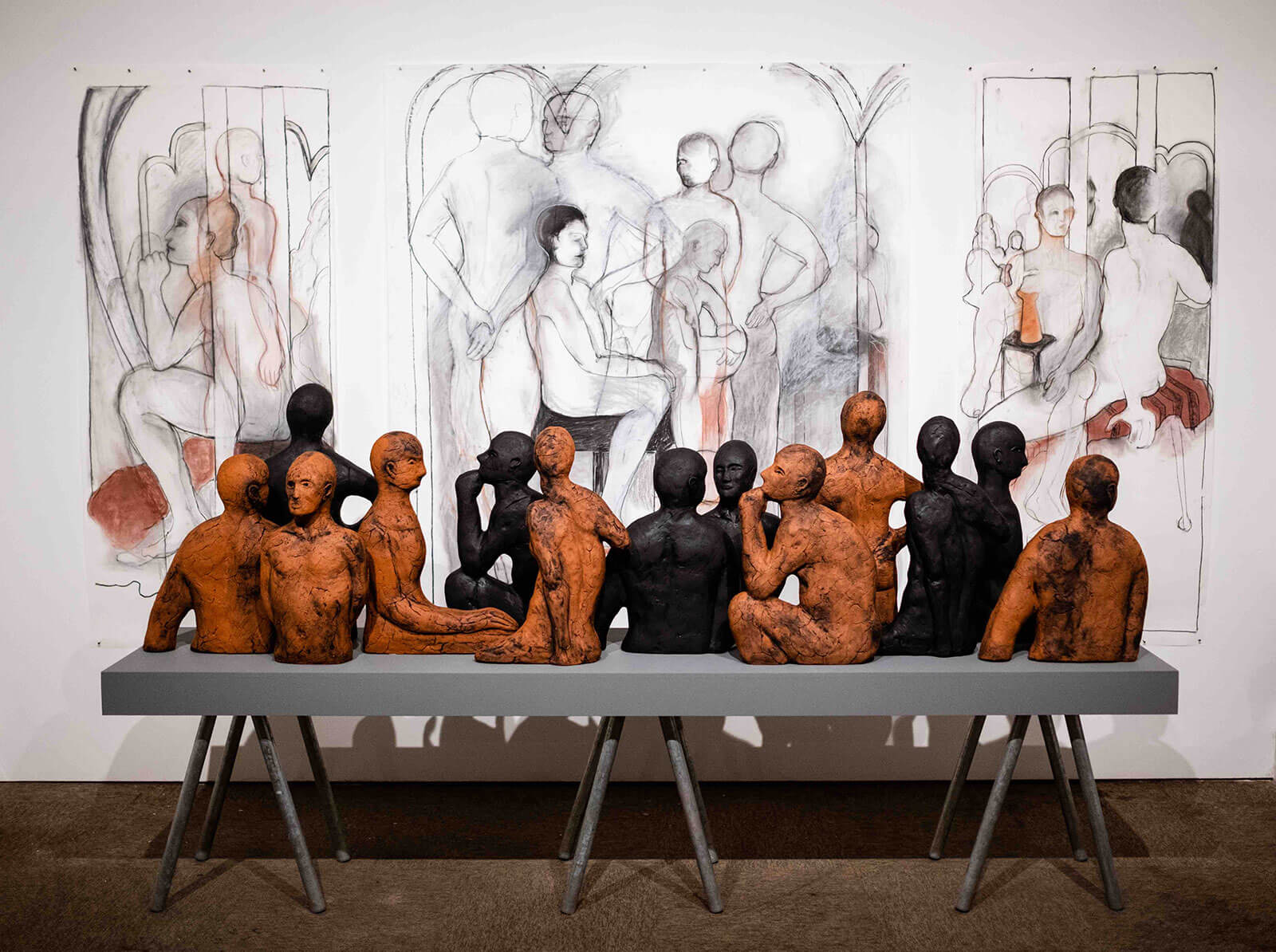

As an aside, it’s fascinating to see Christie Brown and Tamsin van Essen, established names in the field both, experimenting with new directions in their practice.

Christie Brown, ‘Tableau’, 2021

COURTESY: Christie Brown & British Ceramics Biennial / PHOTOGRAPH: Jenny Harper

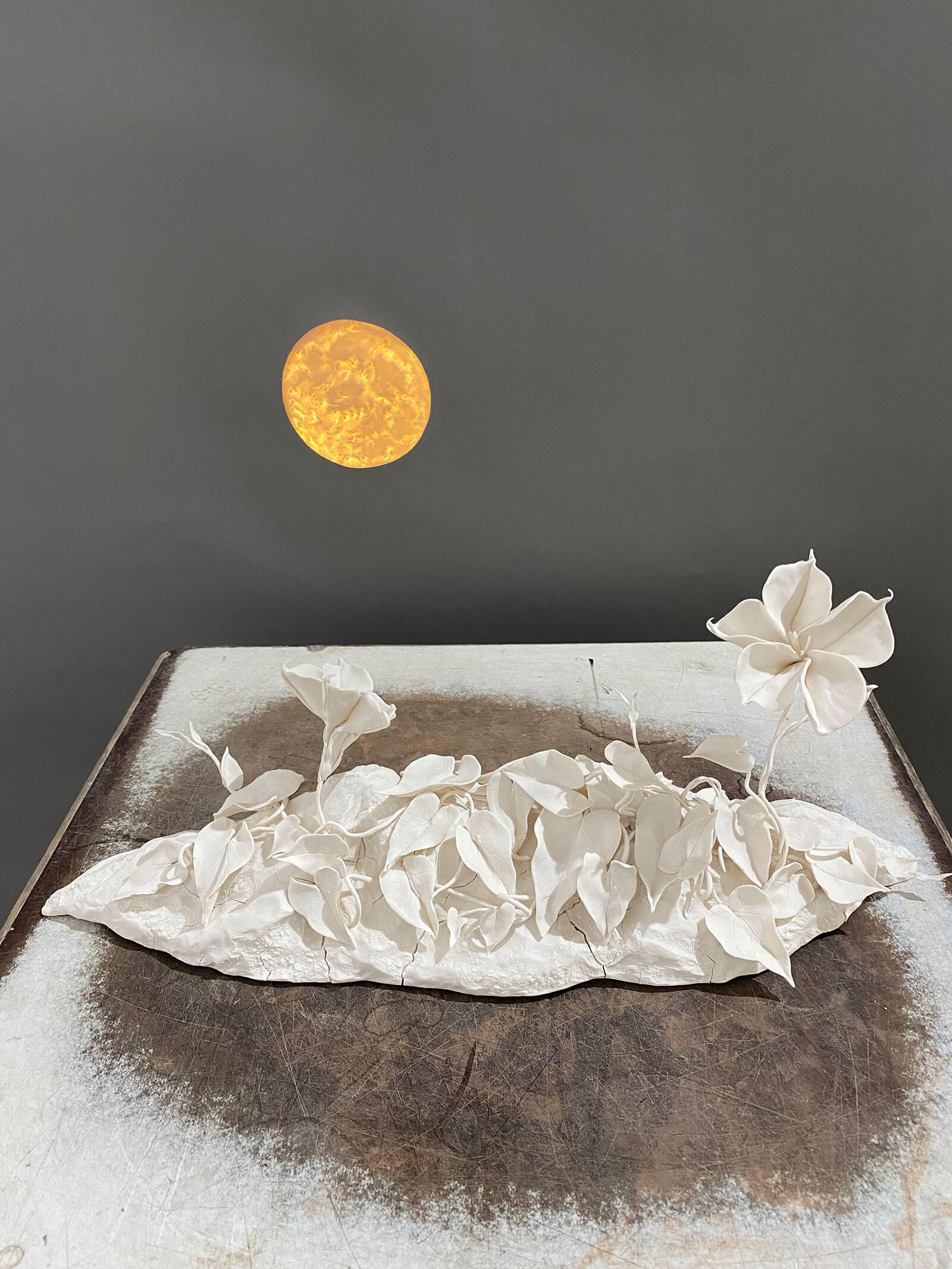

Elsewhere in the building are a clutch of other exhibitions. ‘Fresh’, for example, shows pieces from 25 early career ceramic artists from a variety of backgrounds. Some have emerged from established courses, such as the Royal College of Art and Staffordshire University, a fistful are the product of further education or other routes. Part of the fun is trying to work out who might have gone where. Subsequently, there’s a section devoted to pieces created by artists from the Fresh 2019 cohort – including the likes of Alice Walton, Toni de Jesus and Laura Plant; another given to the BCB’s international work with the Indian Ceramics Triennale and Kasama Potters; and there’s an area displaying commissions from the Leach Pottery’s ‘Leach 100’, which invited four artists to mark its centenary by developing new work in response to its values and heritage.

Amy Hughes, ‘Leach 100’, from Brush Work series, 2021

COURTESY: Amy Huges & British Ceramics Biennial / PHOTOGRAPH: Jenny Harper

In the years since it launched one of the most persistent grumbles I’ve heard about the Biennial is that it doesn’t involve the local community enough. (An entirely understandable gripe, although I sometimes wonder whether people living in Cannes complain there are no movies made by them when the film festival rolls into town.) ‘Stoke Makes Plates’ is an attempt to remedy that. The installation features more than 250 plates that have been made and designed by 120 residents of Stoke-on-Trent and Newcastle-under-Lyme, inspired by the city’s high street.

Stoke Makes Plates at British Ceramics Biennial 2021

COURTESY: British Ceramics Biennial / PHOTOGRAPH: Jenny Harper

Away from the Goods Yard, there’s a small show at the Airspace Gallery, entitled ‘Use and Ornament’, which investigates sustainability and wellness, with artists such as Claire Loder and Katie Spragg, while the hardy perennial of the BCB, Neil Brownsword, has a solo exhibition, ‘Alchemy and Metamorphosis’, at The Potteries Museum. Finally Paul Scott plays with the Spode archive with ‘Gardens of Lyra’ at The Spode Museum Trust Heritage Centre.

Katie Spragg, ‘Cheese Grows Blue’, 2021

COURTESY: Katie Spragg & British Ceramics Biennial

So there is a huge amount of work here, much of it good, and all of it thoughtfully and lovingly curated. The new venue lacks the drama of the Spode factory – the ceilings of the old office are suspended rather than vaulted – but curiously that means you’re more focussed on the pieces themselves rather than the surrounding architecture.

Neil Brownsword, ‘Factory with Rita Floyd’, 2017

COURTESY: Neil Brownsword & British Ceramics Biennial / PHOTOGRAPH: Korea Ceramic Foundation

Perhaps the only criticism that still lingers 12 years on from its launch is that the BCB takes a partial view of ceramics. It concentrates on the studio, artistic side of the field at the expense of the industrial, which seems a shame because there must be stories to tell from the factories that still reside in the city and remain an intrinsic part of its identity.

Mould store at the Spode Works site

COURTESY: British Ceramics Biennial / PHOTOGRAPH: Instruct

This edition of the BCB doesn’t attempt to redress that balance but it will be fascinating to see whether that changes when Wood, who was previously chief executive of Re-Form Heritage, a national charity that supports communities through the regeneration of their historic buildings, based at Middleport Pottery, gets her feet properly under the table.