Radical Acts: Why Craft Matters

An imaginative and provocative way to intervene in a house that offers a dazzling display of Georgian craftsmanship.

Harewood, Yorkshire

26th March – 29th August 2022

Mac Collins, ‘Open Code’, 2022

COURTESY: Harewood House / PHOTOGRAPH: Edvinas Bruzas

“WE ARE NOT offering a display of objects on plinths,” explains Hugo Macdonald, curator of ‘Radical Acts: Why Craft Matters’. For his second Biennial of craft at Harewood House, Macdonald has chosen to focus less on the products of crafts and more on what craft as a practice, as a way of thinking and doing, can discover and teach us.

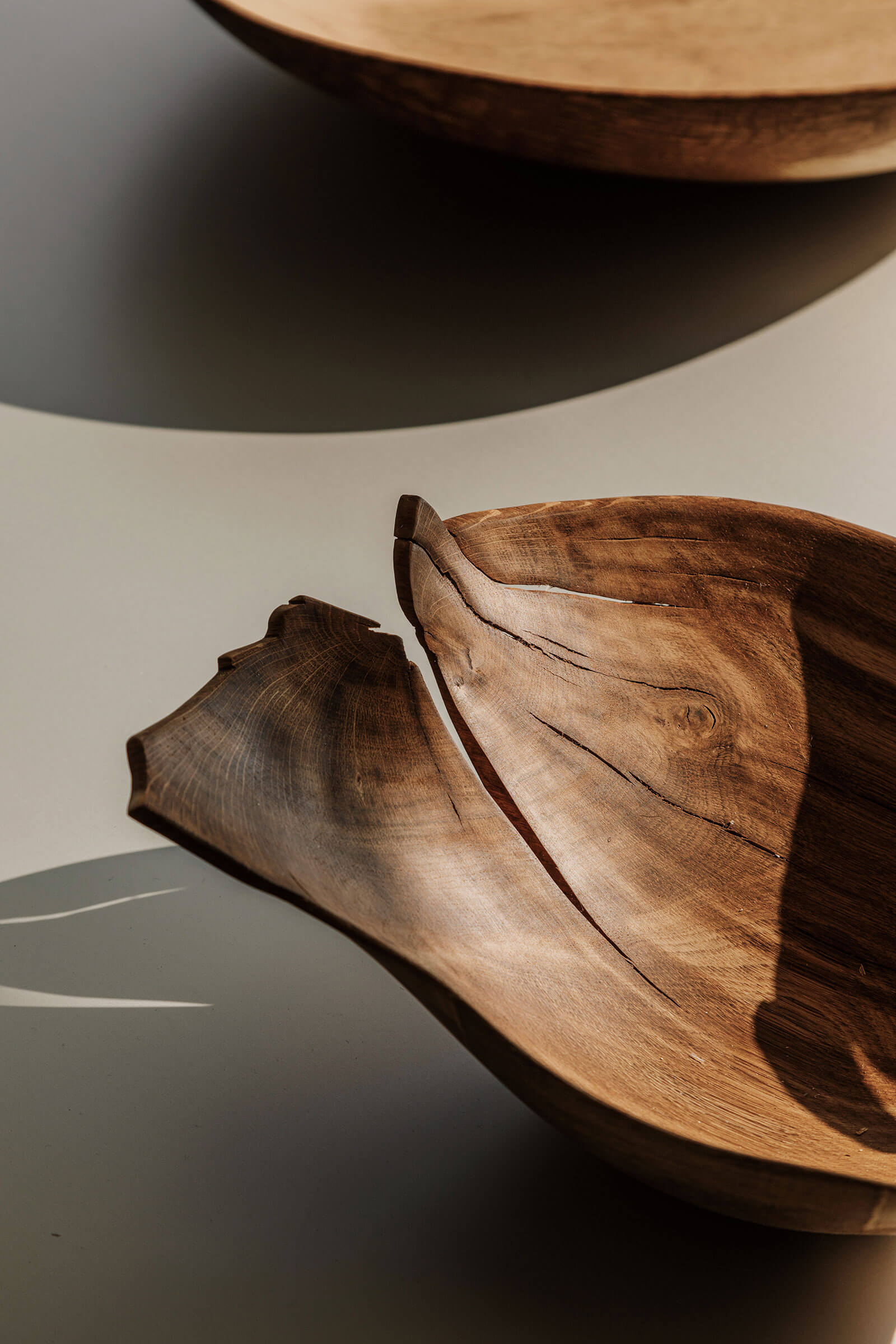

Bobby Mills, ‘Windblown Oak’, 2022

COURTESY: Harewood House / PHOTOGRAPH: Edvinas Bruzas

The sixteen individuals he has chosen to display their work through the house and grounds of this stately home range from furniture designers and woodturners, to social entrepreneurs. Some do produce objects: beautiful silver, copper, wood or ceramic vessels (Francisca Onumah, Bobby Mills, Bisila Noha); striking furniture and architecture (Mac Collins, Michael Marriott, Sebastian Cox), and innovative corn-husk marquetry or table-leaves from salvaged materials (Fernando Laposse, Retrouvius).

Bobby Mills, ‘Windblown Oak’, 2022

COURTESY: Harewood House / PHOTOGRAPH: Edvinas Bruzas

But others use craft to repair garments (Celia Pym), to purify water (Good Foundations International) or create a sustainable clothing business (Community Clothing). What unites them is the use of lateral thinking, resourcefulness, material knowledge and hope to address entrenched global and national predicaments.

Good Foundations International, ‘Ceramic Water Filter’, 1986

COURTESY: Harewood House / PHOTOGRAPH: Edvinas Bruzas

For Macdonald, the work is radical because these ways of thinking and making return us to our roots, to old knowledge, but at the same time they build a bridge to the future – allowing us to address contemporary problems of human connection, equality and social justice, climate change and conservation.

Bisila Noha, ‘The Unnamed Women of Clay’, 2021

COURTESY: Harewood House / PHOTOGRAPH: Edvinas Bruzas

As he puts it, “Radical Acts is about minds and hands working together with social and environmental purpose.” It is an imaginative and provocative way to intervene in a house that offers a dazzling display of Georgian craftsmanship, paid for by that most unethical of businesses – the eighteenth-century transatlantic slave trade.

Celia Pym, ‘The Mending Library’, 2022

COURTESY: Harewood House / PHOTOGRAPH: Edvinas Bruzas

Harewood House was built between 1759 and 1772. Under the direction of the astute and demanding Edwin Lascelles, heir to his father’s sugar and slave fortune, the most sought-after designers were hired. John Carr of York, responsible for some of Yorkshire’s grandest eighteenth-century buildings, designed the exterior. Capability Brown and Humphrey Repton shaped its landscaped gardens, parkland and plantations.

Harewood House

COURTESY: Harewood House / PHOTOGRAPH: Edvinas Bruzas

Robert Adam, then a young Scottish architect beginning to build his reputation, was put in charge of the interiors – creating his first masterpiece. The foremost artists and craftsmen were commissioned for everything from the ceilings to the carpets: William Collins and Joseph Rose for the elaborate plasterwork; Angelica Kauffmann, Antonio Zucchi and Biagio Rebecca for the decorative painted panels; and Thomas Chippendale for the furniture. Over the next two hundred years, fine paintings, sculptures, objects and additional furniture were bought and commissioned.

Francisca Onumah, ‘Murmur’, 2022

COURTESY: Harewood House / PHOTOGRAPH: Edvinas Bruzas

To fight this splendour would be madness. As the current Earl of Harewood, David Lascelles, writes in his book about the house, “There is nothing we can do to change the past, however much we may want to. But we can try to engage with the legacy of that past and so stand a chance of having a positive effect on the future.”

Francisca Onumah, ‘Murmur’, 2022

COURTESY: Harewood House / PHOTOGRAPH: Edvinas Bruzas

Since the 1980s, the house has been run as an educational charitable trust for public benefit. It has opened itself to the reactions and responses of different artists – including the glass artist Chris Day, who created an entire body of work for the nearby All Saints’ Church (exhibited last year), inspired by rum bottles discovered in the cellar of the house. If the opening of the house to the public is some kind of reparation, Macdonald has magnified that action through his choice of exhibitors. All engage in some way with repair, reuse and restoration, whether straightforwardly in the case of Retrouvius’s tabletop, or more conceptually.

Retrouvius, ‘Leftovers’, 2022

COURTESY: Harewood House / PHOTOGRAPH: Edvinas Bruzas

Nottingham-born designer Mac Collins has chosen to make a games table and chairs to place beneath the portrait of Edwin Lascelles by Sir Joshua Reynolds in the Cinnamon Drawing Room, and has developed a set of dominoes to be played there. On a monochrome platform to frame his installation – and to cut it off from the warm-coloured surroundings where Edwin Lascelles and his friends would have retired to play cards after dinner – Collins honours a game much loved in Jamaica, where his grandmother is from. As he says, “Too often the Caribbean community is omitted from these kinds of spaces.” He has woven this thread of history back into the story but as a determined act: not quietly, not violently, but demonstrably.

Mac Collins, ‘Open Code’, 2022

COURTESY: Harewood House / PHOTOGRAPH: Edvinas Bruzas

Meanwhile, the quiet work of Francisca Onumah, a human-like grouping of beautifully precise oxidised copper and silver vessels, with the patterned battering of the hammering tools and the seams of the sheet metal still visible, stands in front of the outrageously gilded and swagged Chippendale bed in the State Bedroom. If introversion and vulnerability here converse with confident display, in the next room, designer Michael Marriott’s beguiling, resourceful makeshift scene-setting, using a bewildering array of salvaged objects and materials, offers an extrovert counterpoint to Robert Adam’s ornate ceiling. Make do and mend meets lavish embellishment, in a spirit of good humour.

Michael Marriott, ‘Kioskö’, 2022

COURTESY: Harewood House / PHOTOGRAPH: Edvinas Bruzas

Sebastian Cox’s delightful tree-house in the grounds, its walls woven from English larch, is a by-product of his “radical act” – a tree-management plan for Harewood that involves cutting down surplus trees and using local wood traditionally spurned by timber merchants.

Sebastian Cox, ‘Sylvascope’, 2022

COURTESY: Harewood House / PHOTOGRAPH: Edvinas Bruzas

Meanwhile, the show itself, all its display plinths and signage, has been constructed from 90% recycled aluminium provided by Novelis, the world’s largest aluminium recycler. Once the biennial closes, the metal will be returned for reuse. For in this exhibition, even the plinths are part of the story.

‘Radical Acts: Why Craft Matters’ at Harewood, Yorkshire.