Luxes

An exhibition tracing the evolution of luxury and our relationship to it.

Musée des Arts Décoratifs (MAD), Paris

Until July 18th 2021

Exhibition view

COURTESY: Musée des Arts Décoratifs / PHOTOGRAPH: Luc Boegly

The Musée des Arts Décoratifs (MAD), founded in Paris in 1864 to celebrate the links between art and industry, is home to over 800,000 objects, many of them luxurious. For the exhibition ‘Luxes’ (‘Luxuries’), which closes this weekend, it presents just over 100, in a succinct exploration of the concept of luxury over the past 4,000 years. Olivier Gabet, MAD’s director, conceived the idea after a prior exhibition on 10,000 years of luxury in 2019 at the Louvre Abu Dhabi, which MAD was involved in creating. It’s the universality of luxury across different cultures, civilisations and eras, Gabet says, that renders the subject fascinating.

Before the term ‘luxury’ emerged, it was the raw materials themselves that were prized. Trading them along the Silk Road paved the way for their transformation into desirable goods and contributed, eventually, to the international development of taste.

Exhibition view with Gloria Cortina’s ‘Synergy Bench’, 2016

COURTESY: Musée des Arts Décoratifs / PHOTOGRAPH: Luc Boegly

Of particular interest for readers of The Design Edit, is how furniture and lighting are contextualised in this framework. Immediately eye-catching is the vast, opulent, Art Deco chandelier, its ornamental lighting fixtures emanating like a fountain or fireworks, created in 1925 by Cappellini-Venini, back then a young Venetian firm.

A few years later in France, a radical and minimalist approach to luxury emerged, represented in this exhibition by Jean-Michel Frank’s elegant, pared-down furniture with simple lines and humble straw marquetry. This is presented alongside Alberto Giacometti’s bronze figurative floor lamp, ‘Tête de Femme’ (1934), created for Frank, and Coco Chanel’s ‘Little Black Dress’ (1925), made in a similar spirit of modernity. The French writer François Mauriac described this upending of ostentatiously displaying wealth as “the strange luxury of nothing”.

Several decades of twentieth-century furniture design are overlooked, in favour of focusing on fashion. The exhibition then takes us to today’s era and explores how materials and manufacturing methods relate to luxury. For instance, Benjamin Graindorge’s ‘Fallen Tree’ (2011), made from sculpted oak with protruding branches, critiques how nature should be cherished in an epoch of deforestation. It resonates with fashion made from organic cotton, as an expression of ecological awareness.

Exhibition view with Benjamin Graindorge/YMER&MALTA ‘Fallen Tree’, 2011

COURTESY: Musée des Arts Décoratifs / PHOTOGRAPH: Luc Boegly

Further along in the exhibition is Gloria Cortina’s geometric ‘Synergy’ (2016) bench, made from five variously sized cubes made from polished and patinated brass and nickel, edited by New York’s Cristina Grajales Gallery. “It expresses several forms of luxury,” co-curator Cloé Pitiot says. “The [cubic] pieces were handmade by craftsmen in Mexico and the project references the heritage of the ancient Mayan civilisation and its mathematical knowledge.” Associations between furniture and fashion being a theme of the exhibition, the bench is juxtaposed with Issey Miyake’s white polyester dress, ‘Colombe’, its pleats evocative of a bird’s wingspan.

Another display features Christian Astuguevieille’s bright red leather chair for the ‘petit H’ Hermès line – showcased next to a Hermès saddle and riding boots festooned with black feathers. “The ‘petit H’ line is about upcycling offcuts of luxury and inviting artists and designers to create new objects with them,” Pitiot remarks. It’s an example of how luxury brands can question their role in the industry and how perception of luxury has diversified.

Exhibition view with Christian Astuguevieille’s chair for Hermès ‘petit H’ line

COURTESY: Musée des Arts Décoratifs / PHOTOGRAPH: Luc Boegly

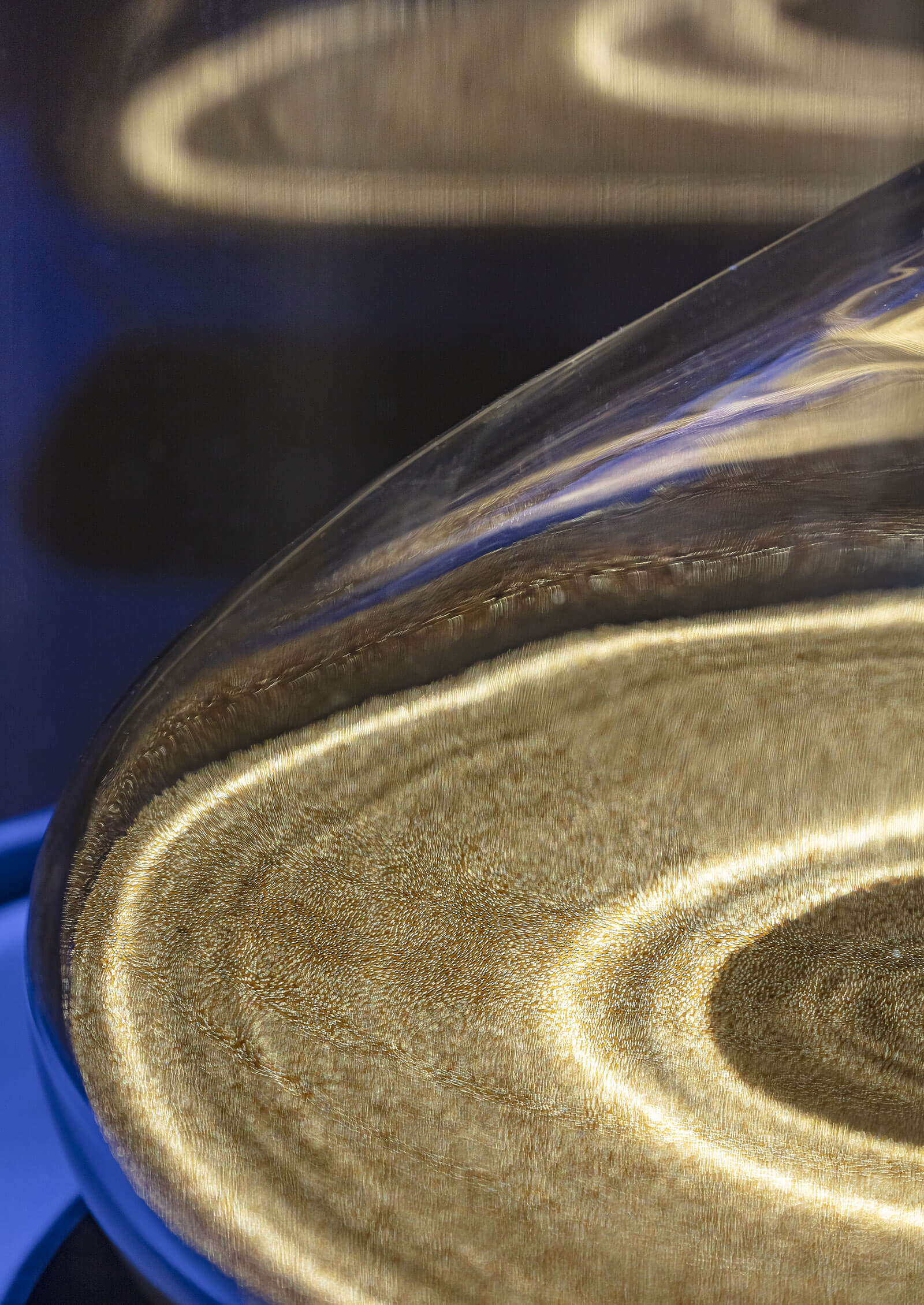

The exhibition closes with Marc Newson’s ‘The Hourglass’ (2015), which is based on a traditional chronometer and filled with millions of miniscule gold beads. As access to luxury goods has, to an extent, become global and more democratic, it alludes to the preciousness of natural reserves and, more importantly, to the luxury of time as seconds slip away.

Marc Newson, ‘The Hourglass’, 2015

COURTESY: Musée des Arts Décoratifs / PHOTOGRAPH: Luc Boegly

“Before the term ‘luxury’ emerged, it was the raw materials themselves that were prized …”

Marc Newson, ‘The Hourglass’, 2015 (detail)

COURTESY: Musée des Arts Décoratifs / PHOTOGRAPH: Luc Boegly

“Trading them along the Silk Road paved the way for their transformation into desirable goods”

Luxes at MAD Paris.