LDF / Matt Smith 2020

His subtle transformations of story-telling objects reveal hidden narratives.

14th September – 9th November 2020

99 Bishopsgate, London, EC2M 3XD

Matt Smith

COURTESY: Cynthia Corbett & Matt Smith

THE LOBBY OF 99 Bishopsgate, a sleek high-rise office block in the heart of the City of London, is an unlikely location for an exhibition of works by the British artist Matt Smith. Smith is, after all, known for his site-specific interventions in National Trust houses and museums such as the Fitzwilliam in Cambridge, the V&A and Oxford’s Pitt Rivers Museum; he is not a fan of white cube spaces and things on plinths. And his pieces, made chiefly in ceramic and textile, tend towards the domestic rather than the commercial.

The venue was chosen because it is owned by Brookfield Properties, the global real estate management company behind the Brookfield Properties Crafts Council Collection Award, which was awarded to Smith at Collect earlier this year. The two tapestries and four signature ceramic assemblages Brookfield Properties bought and then gifted to the Crafts Council Collection as a result of the prize, form the core of the exhibition. They are joined by 14 other works spanning the last ten years of Smith’s practice.

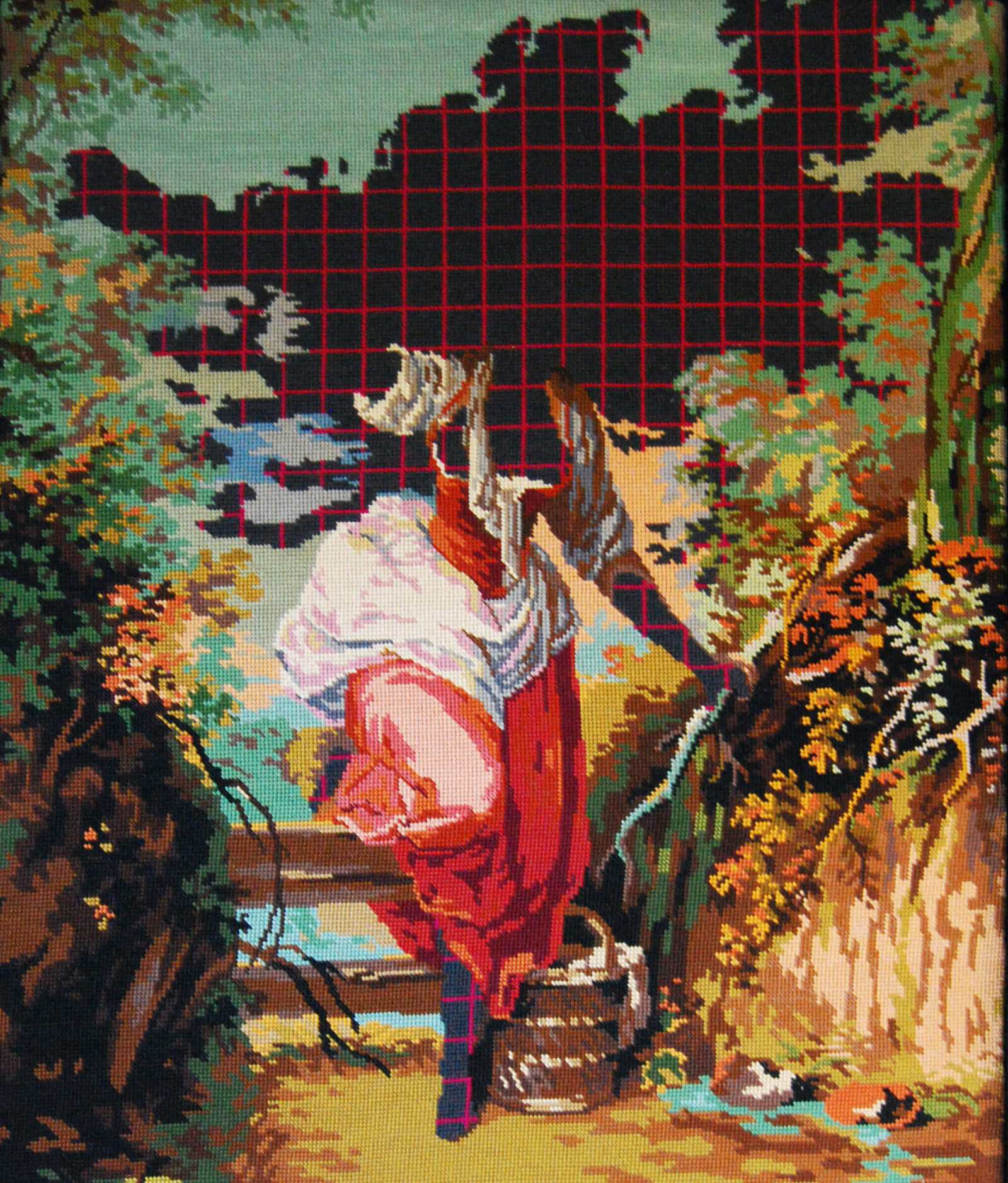

Matt Smith, ‘Hide and Seek’, 2019

COURTESY: Cynthia Corbett & Matt Smith

‘Pastorale’, made in 2019, is part of a series of tapestries that feature an area of newly stitched pattern where the original subject’s faces once were, and a ceramic composition called ‘The Gift’. Made for his 2013 show at the National Trust-owned Tudor mansion The Vyne, this collection of figurines threaded together with strings of pearls refers to objects Horace Walpole suggested the house’s 18th century owner, John Chute, should purchase for his collection. Smith placed the piece under The Vyne’s grand staircase, the hidden positioning nodding not only to the fact that Chute ignored Walpole’s advice but also to the intimate, but unacknowledged, relationship between the two men. Here, as with so much of Smith’s work, the setting is part of the art.

So, when I speak to Smith via Zoom at his office in Stockholm, where he is Professor of Craft at Konstfack (University of Arts, Craft and Design) my first question is how he thinks his work will be understood in this new, rather anonymous, environment. “When you take away all the extra layers that a museum or a historic house brings, the work reads in a different way,” he says. “That’s exciting because it puts the focus on the actual piece, as an object.”

Matt Smith, ‘Egg Headed Boy’, 2018

COURTESY: Cynthia Corbett & Matt Smith

“My upbringing gave me a mistrust of grand narratives and shared beliefs. It showed me that for every fact, there will be a counterfact”

Matt Smith, ‘Pearl Girl’, 2020

COURTESY: Cynthia Corbett & Matt Smith

“Ever since, I have been trying to work out what narratives are being silenced because we are looking in one particular direction”

Smith’s practice is driven by a desire to change the story, to make us look and then look again and to continually question what we see. When he was nine, the family moved from Cambridge to Sao Paulo, an experience he describes as “possibly the most useful thing that happened to me.” He went to the local school where lessons were, naturally, taught from a Brazilian perspective. “To suddenly hear history told from a global South point of view, rather a global North one, fundamentally shifted my view of Britain and Europe,” he explains. “That shock of mis-recognition of all the things we grew up with and the certainties we got taught had a long-term impact on my mistrust of grand narratives and shared beliefs. It showed me that for every fact there will be a counterfact and, ever since then, I have been trying to work out what other narratives are being silenced because we are looking in one particular direction.”

Location is one of ways he does this is, but it is not the only one. His work is also largely made from the kinds of story-telling objects that have long filled our museums and stately homes. His ceramics are often assemblages of 18th and 19th century figurines – ‘Egg Headed Boy’ for example, made as part of his Wunderkammer II series (and which won him ‘Object of the Fair’ at Collect in 2018), is a mass-produced figurine on a black base, sporting a black, egg-shaped sphere over its head. His textile pieces are interventions in existing tapestries in which he literally unpicks and re-stitches the past, replacing the faces of the central subjects with areas of pattern. At first glance, these textile pictures appear politely decorative, then you notice there is something strange – there are bodies but no faces. You don’t quite know where to look. The experience is disorientating and unsettling.

Matt Smith, Study in Pink and Gray’, 2019

COURTESY: Cynthia Corbett & Matt Smith

SMITH BEGAN HIS professional life working in museums then, in 1996, he re-trained as a ceramicist, first at London’s City Lit and then at the University of Westminster. He chose ceramics not because he wanted to get hands on with clay, but because “it has legacy.” “I’ve always been fascinated by what material culture gets collected,” he explains, “and while that’s partly down to collecting patterns, it also has a lot to do with the materials; with what lasts. Because clay lasts, it forms quite a large part of the narrative of historical understanding.”

Installation at Collect, 2018

COURTESY: Cynthia Corbett & Matt Smith

Smith refers to himself as ‘a hybrid artist/curator’ rather than a craftsperson, but he has a studio at his home in Ireland and spent every day this summer inside it, making. He describes this making as a ‘compulsion’. When he speaks about the objects he creates, he is as passionate and knowledgeable about their physical properties as their meaning. When I ask him about Parian, for example, a material he’s worked with since he first encountered it as Artist in Residence at the V&A in 2015/16, he talks not only about how this marble substitute was used to memorialise ‘eminent’ Victorians, but also about what it is like to work with. “It’s incredibly volatile,” he says, “so it’s me versus the material, an experience that’s somewhere between a dance and full on boxing match.” Even ‘Egg Headed Boy’, for all its symbolism, is for him “very much about process.” “If you fired it altogether,” he explains, “the Parian would fire at a temperature where the colour and gilding would go – so it doesn’t follow the rules of traditional ceramics.”

It is this deep knowledge of and respect for craft, combined with his academic thinking, that makes Smith’s work so successful. He is a fine artist fascinated by the power of the handmade object to hold meaning, tell stories and, above all, to disrupt the mainstream narrative. “Making,” he says, “has the potential to give agency to different ways for the world to be.”

99 Bishopsgate – Brookfield Properties and the Crafts Council present a collection of works by Matt Smith, in a free exhibition.

For further information about Matt Smith’s work, contact Cynthia Corbett Gallery.