Milan Design Week 2021 / A Perspective

Milan exemplifies design – Astrid Malingreau looks at this year's Design Week through a historical lens.

SPREAD, ‘Much Peac, Love and Joy’ at Alcova

COURTESY: © IMG DSL Studio-Piercarlo Quecchia

ALL AROUND THE Italian capital visitors read the message ‘Design is Milano is Design’. It was like a manifesto reminding the world that Milan remains the absolute centre of design.

The first Salone, as we know it, was created in 1961 by a group of manufacturers to demonstrate the innovative excellence of Italian furniture. As well as showing off Italian craftsmanship and reaching out to international markets, the furniture fair reflected critical shifts in our ways of living. Since then, ‘Made in Italy’ has become a distinctive hallmark, and the Salone has become an international gathering complemented by a mosaic of events across the city, known as the Fuorisalone.

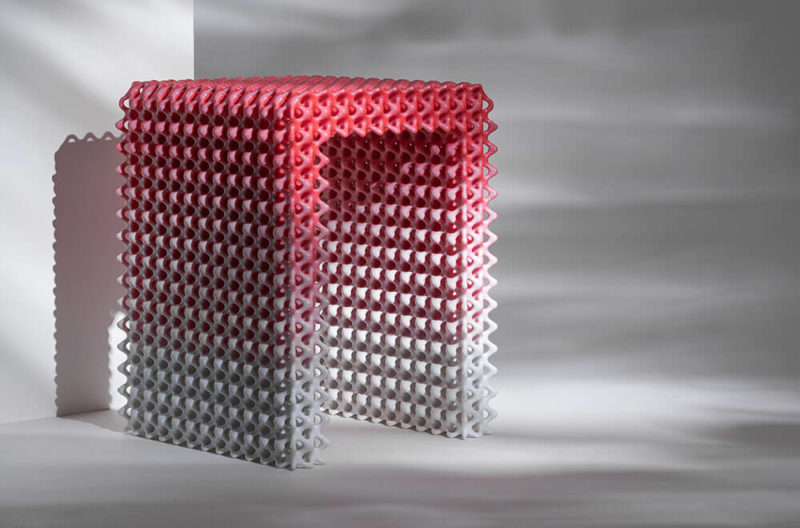

Analogia Project, ‘Arcoiris Collection’, 2020

COURTESY: Nilufar / PHOTOGRAPH: © Daniele Iodice

For one week every year, Milan becomes the place for analysis, new ideas, experimentation, validation and the conjuring of utopias. It was Milan that inaugurated the 1950s Italian economic miracle that transformed the country into a world economic power. The city has now grown to define itself at the intersection of entrepreneurial optimism, audacity, industrial ingenuity and imagination – with design at the centre of the stage.

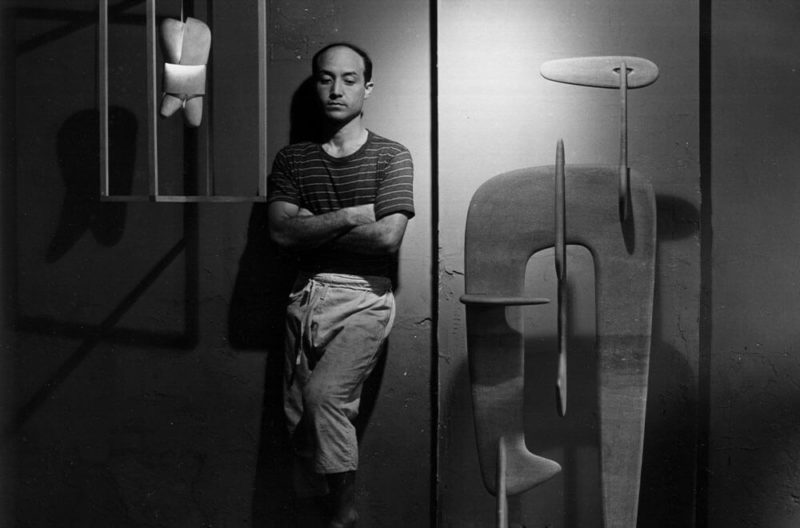

Pietro Consagra, ‘Matacubi’, 2021

COURTESY: Nilufar

The 2021 edition of Milan Design week followed a brutal Covid-related interruption, coming at a time when our ways of living and resource use are strongly challenged. Like a kaleidoscope of hypotheses, events across the city questioned what it means to live well and how our lives can be reshaped and reorganised.

Installation view, Davide Pizzigoni, ‘Quasi Vuoto’, 2021

COURTESY: Luisa delle Pianne

Memphis spirit

The 2021 edition of the furniture fair was renamed the ‘supersalone’, to mark the unique format of this unusual year. Events and exhibitions looked back at the history of Italian design and of the furniture fair itself, as well as to the future.

Historical design was not a big part of the Fuorisalone but particular attention was given to the Memphis group. From 1980 to 1987 this eclectic group of designers disrupted the domestic space with furniture, lighting, textiles and objects that challenged formal values and the parameters of functionality. In response to emerging capitalist forces and technological evolution, Memphis dreamt up new ways to inhabit the world with humour, irreverence and freedom from conventions. Post Design gallery offered a combination of their iconic creations (still in production) alongside collaborations in the non-conformist Memphis spirit with new and seasoned designers.

Installation view, ‘Memphis’

COURTESY: Post Design

The main focus here was the latest collection of furniture designed by Masanori Umeda entitled ‘Utamaro’. Just as with his ‘Tawara’ boxing ring – made famous by the Memphis group picture in 1981 – the various seats combine a traditional Japanese aesthetic with flashy colours, tubular metal structures, asymmetry, flamboyant silks and lacquered surfaces.

Masanori Umeda, ‘Utamaro’ sofa, 2020

COURTESY: Post Design

Although Memphis dissolved only seven years after its creation the related works remain intriguingly contemporary. To honour the group’s pioneering vision, Abet Laminati and curators Giulio Iacchetti and Matteo Ragni commissioned eight designers to imagine how the spirit of Memphis would manifest itself today. The result was an exhibition ‘SuperSuperfici!’ at the ADI Design Museum, where the designs cleverly delved into the philosophical and conceptual roots of the movement to give it a contemporary perspective.

The dialogue with history continued in playful mood at Rossana Orlandi gallery, with the ‘Textile Ruins’ of Sergio Roger. These are sculptures made from recycled fragments of cloth, inspired by classical sculpture. Meanwhile, at the Via della Spiga headquarters of Nilufar, Andrea Mancuso offered a visually striking take on marble, echoing the Roman art of pietradura inlay with his curvy and colourful collection of furniture.

Installation view, Sergio Roger, ‘Textile Ruins’, 2021

COURTESY: Rossana Orlandi gallery / PHOTOGRAPH: Marco Menghi

Natural talents

This edition of the Fuorisalone also offered an array of strategies developed by designers, in confrontation with the climate emergency, to engage and collaborate with nature.

The third edition of Alcova, curated by Joseph Grima with Space Caviar and Valentina Ciuffi with Studio Vedèt, presented more than 50 works ranging from experimental prototypes to consumer products, immersive installations and architectural constructions – all exploring new approaches to materials and forms. Exhibited in the former Baggio military hospital, highlights included a portable baby incubator for war zones; biodegradable medical uniforms; the ‘Hot Wire Extensions’ furniture of Fabio Hendry; and the ‘Belt’ furniture by Daisuke Motogi from DDAA Lab.

DDAA LAB, ‘Belt Furniture’ at Alcova

COURTESY: Astrid Malingreau

“The ‘Belt furniture’ is fixed without glue or nails …”

DDAA LAB, ‘Belt Furniture’ at Alcova (detail)

COURTESY: IDEM

“… but only with belts used for truck beds”

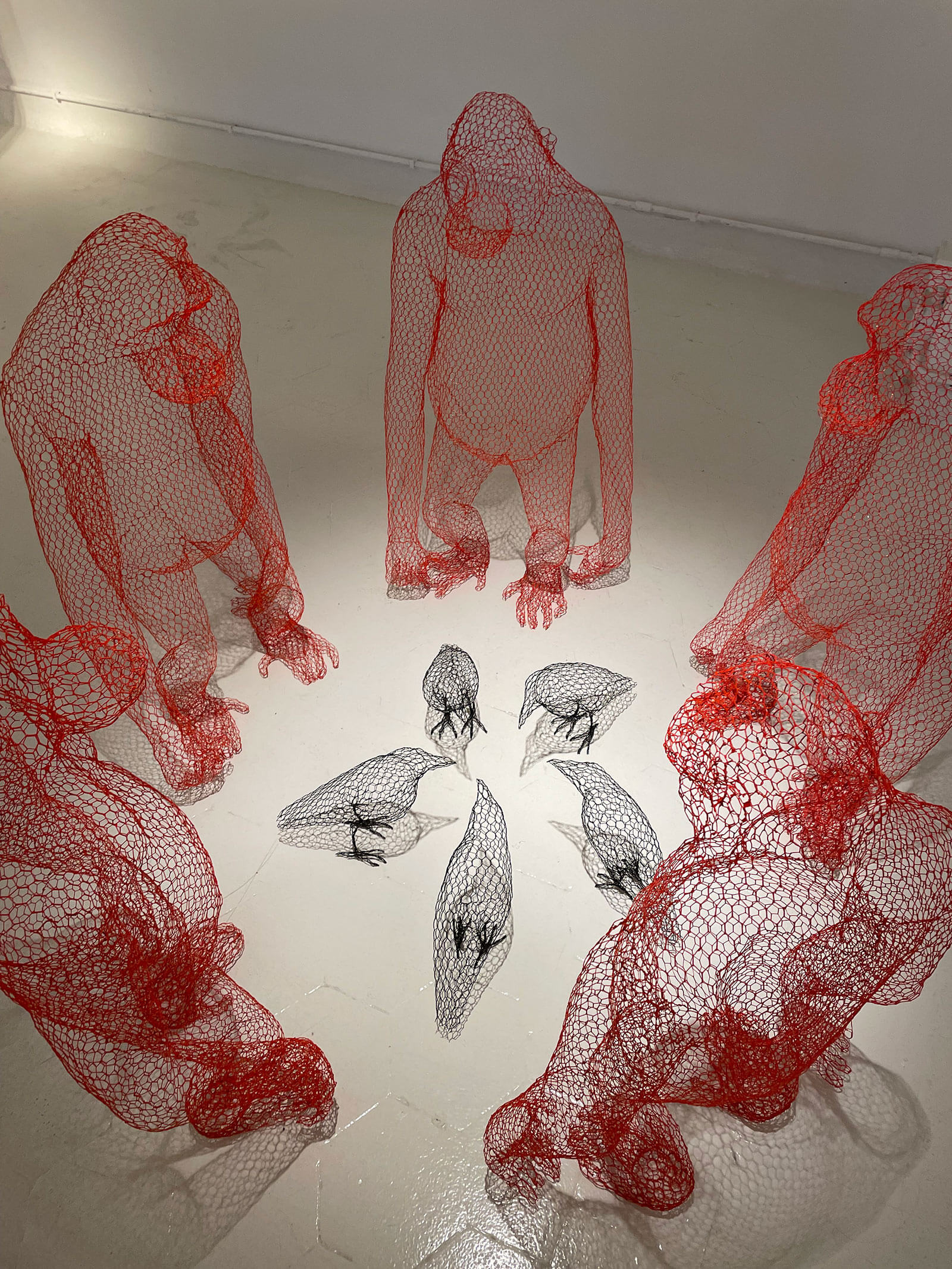

At the gallery Rossana Orlandi, Benedetta Ubaldini Mori created a dreamy landscape of creatures created from chicken wire, with the evocative title ‘What would I be without you’.

Installation view, Benedetta Ubaldini, ‘What would I be without you’, 2021

COURTESY: Rossana Orlandi gallery

In addition, the gallery exhibited the winning project for the Urban and Public Furniture Design section of the RO Guiltless Plastic Prize, founded by Orlandi to encourage designers to address sustainability and waste head on. The ‘Plastic River Project’ by Álvaro Catalán de Ocón comprised a monumental collection of rugs woven with yarn made from recycled plastic debris, depicting some of the most polluted rivers.

Álvaro Catalán de Ocón for GAN, ‘Ganges’ rug from the Plastic Rivers collection, 2021

COURTESY: Rossana Orlandi gallery

The sourcing of materials is central also to the work of the talented designer Khaled El Mays, who imagined a series of furniture for the Nilufar depot. The founder of the eponymous Beirut studio offered a selection of unique handmade pieces produced by artisans in the Beqaa valley (Lebanon) with local materials such as wood or recycled animal skin. His aim was to show the diversity of resources one could find in a single location.

Installation view, Khaled El Mays, ‘JUNGLE’, 2021 (installation by Federica Perazzoli)

COURTESY: Nilufar / PHOTOGRAPH: © Mattia Iotti

Perhaps the most striking partnership with nature was evident in Polish designer Marcin Rusak’s solo exhibition ‘Unnatural Practice’, curated by Federica Sala, at Ordet. Conceived as an exploration of the designer’s studio, left abandoned and and starting to petrify, his creations were presented as ‘a living catalogue of the decaying, ephemeral and preserved’. Born into a family of horticulturists, Rusak uses flowers and plants as materials for his pieces and makes the process of their conservation and/or decomposition central. The resulting works hover between a scientific experiment and a Baudelarian vision.

Installation view, Marcin Rusak Studio, ‘Unnatural Practice’

COURTESY: Marcin Rusak Studio

Carwan gallery, which represents Rusak, also introduced the new lightning creations of Omer Arbel, in the intimate setting of Nicolas Bellavance-Lecompte’s apartment. “Since we can’t fully control the process, we let the material dictate the final shape,” explained the designer. The pendant ‘100’ and ’40’ are the combination of individual glass bubbles shattered together to form one interlocking glass piece. This creation called for a collaboration of multiple glass artists within the Bocci glass studio.

Omer Arbel, ‘100’ pendant, 2021

COURTESY: Carwan Gallery

Futuristic visions

Some designers took a step further in imagining future domestic scenarios. In the nunnery utility rooms at Alcova, the collective Objects of Common Interest exhibited ‘future archeology’. The visitor entered what appeared to have been a kitchen to discover a series of objects defined as ‘pure shapes and spatial gestures’. Their undefined materials and neotenic shapes gestured to as yet unknown ways of being.

Installation view, Etage Projects x Objects of Common Interest

COURTESY: © IMG DSL Studio-Piercarlo Quecchia

Equally interested in potential – the space of becoming – as opposed to the present world, Davide Pizzigoni’s thought-provoking exhibition ‘Quasi Vuoto’ (‘Almost Empty’), at the venerable Galerie Luisa Delle Piane, interrogates the fundamental aspects of our relationship with space. Emptiness is omnipresent because it can contain everything, noted Ettore Sottsass. Pizzigoni materialises this abstract idea of emptiness through his three-dimensional coloured quasi geometric objects, whose shapes deviate slightly from the expected geometrical forms.

Installation view, Davide Pizzigoni, ‘Quasi Vuoto’, 2021

COURTESY: Galerie Luisa Delle Pianne

Finally, Andreis Reisinger’s proposition for the future is a combination of digital and ‘real-life’ world, dialoguing together to create new possibilities for our interiors. On the second floor of the Nilufar depot, the visitor is invited to embark on the designer’s ‘Odyssey’. On each of the three walls was projected a 3D film rendering of an otherworldly landscape, with a piece of furniture standing in our physical world, as if it had been extracted from the digital realm.

Andrés Reisinger, ‘Complicated Sofa’, 2021

COURTESY: Nilufar

This year might not have offered the most coherent programme but it certainly displayed a lively design scene eager to answer to the challenges of the coming decades.