NGV Triennial 2021

Commissioned first, curated later: a reversed methodology that has allowed this ambitious exhibition to speak volumes.

Until 18th April 2021

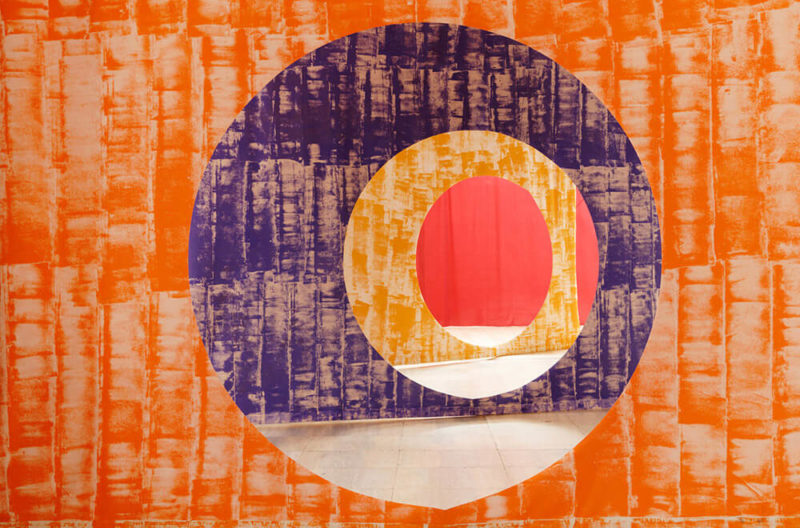

Installation view of Daniel Arsham’s ‘Hidden figures’, 2020 and Fred Wilson’s ‘To die upon a kiss’, 2011

COURTESY: Fred Wilson & Perrotin Gallery / PHOTOGRAPH: Sean Fennessy © Fred Wilson & Pace Gallery

THE CURATORIAL DIRECTION of the National Gallery of Victoria’s (NGV) Triennial emerged from a decision to step back to gauge the full view. Rather than curating towards a determined theme, the organisers of the art and design extravaganza began by overseeing commissions and then later invited critics and scholars to interpret the overall mosaic these new commissions created. This reversed methodology has led, according to the Melbourne museum’s Senior Curator of Contemporary Design and Architecture, Ewan McEoin, to “a porous and issues-led representation of what is happening right now, not simply what one person is thinking about the present.”

The ambitious show, which occupies the entirety of the museum’s 1968-dated Brutalist building, sits on four thematic pillars of illumination, reflection, conservation and speculation. These themes are intertwined across the galleries, which also showcase the museum’s renowned collection of predominantly classical European art, design and decorative objects.

Installation view of Cecilie Bendixen’s ‘Cloud formations’ collection, 2020

COURTESY: © Jim Shaw © Cecilie Bendixen & Simon Lee Gallery / PHOTOGRAPH: Tom Ross

Conceived during Melbourne’s massive gold rush in the mid-19th century, the museum boasts an enviable collection of over 77,000 objects, with narratives awaiting discovery in its dark corners. “The idea of illumination comes into effect with discussions of colonisation, racial representation, and social structures,” explains McEoin about the Triennial’s intervention into the permanent display. “A new material époque,” he adds, is another issue that has risen organically from the landscape drawn by commissioned artists in response to environmental decline and extinction of species.

Installation view of Talin Hazbar’s ‘Accretions’, 2020

COURTESY: Talin Hazbar & NGV Triennial / PHOTOGRAPH: Sean Fennessy © Talin Hazbar

The first Triennial gathered an audience of 1.2 million, the second may struggle to reach that during a pandemic – but free admission, a 5,000-person occupancy capacity and additional late-night programming have helped to draw over 250,000 visitors since its opening in mid-December. The event remains a local spectacle, with an average of three visits per audience and local philanthropy that has so far raised AU $10 million for commission acquisitions.

In scale, the projects range from the immersive to the subtle. A full-day commitment is needed to discover the details in expansive take-overs – such as Fallen Fruit’s flamboyant botanical wallpapers, or Porky Hefer’s whimsical creatures made from the detritus of modern life. These huge works sit alongside singular statements, for example, Australian designer Jonathan Ben-Tovim’s kinetic lamp of discarded inflated airbags, ‘An ode to the airbag’ (2019), positioned by Le Corbusier’s Modernist chaise lounge from the collection. Rive Roshan’s ‘Colour dial table, sunrise light’ is a circular glass table that operates in a similar way to a sundial and casts shifting hues onto the collection’s classical landscape paintings in similarly lush brushstrokes.

Installation view of Patricia Urquiola’s ‘Recycled woollen island’, 2020

COURTESY: Patricia Urquiola & NGV Triennial / PHOTOGRAPH: Tom Ross © Patricia Urquiola Studio, Milan

The Design Edit has selected four highlights from the show, some of which will join the museum’s permanent collection after the Triennial closes. An additional building due for completion in a few years will emphasise the museum’s growing modern and contemporary collection of art, design and architecture.

Faye Toogood, ‘Downtime: Candlelight wall scenography and Family busts and Roly-poly chair / Water’, 2020

Faye Toogood’s ode to light illuminates the collection’s 17th and 18th century Flemish paintings with masterful explorations of luminescence, alongside collaged tapestries which the British designer made in Belgium. Similar to Dutch masters, Toogood washes her work – as well as the pieces she chose from the museum archive – in light’s three forms: daylight, candlelight, and moonlight. These differing illuminations are exhibited in three separate rooms. The soft light allows overlooked themes of domesticity within the paintings to emerge from the darkness.

Installation view of Faye Toogood’s ‘Downtime: Candlelight wall scenography and Family busts’, 2020

COURTESY: Faye Toogood & NGV Triennial 2020 / PHOTOGRAPH: Tom Ross © Faye Toogood

The Enlightenment’s representation of womanhood and female labour, and its relationship to botany through still lifes, provide a backdrop to Toogood’s large scale abstract family busts and biomorphic glass formations, furniture, and maquette sculptures from her London studio. McEoin is particularly fascinated by the “soothing atmosphere and full sensory experience” in the candlelight room.

Installation view of Faye Toogood’s ‘Downtime: Candlelight wall scenography and Family busts’, 2020

COURTESY: Faye Toogood & NGV Triennial 2020 / PHOTOGRAPH: Tom Ross © Faye Toogood

Talin Hazbar, ‘Accretions’, 2020

It is not coincidental that Talin Hazbar’s four ornate light shades bear a close resemblance to rib cages or fishing nets. Hazbar is based in Sharjah, a port city in the United Arab Emirates. Inspired by the common sight of fishing nets dancing in and out of the water on wooden poles, she repeatedly immersed her steel structures into the seawater to encourage organic growth across their surfaces. Hazbar is one of many artists who, McEoin says, “works against an extractive industrial era mentality towards nature and draws attention to urgent paths in design, such as bio-futurism.”

Talin Hazbar, ‘Accretions 1-5’, 2020 (detail)

COURTESY: Talin Hazbar & NGV Triennial / PHOTOGRAPH: Alex Callueng © Talin Hazbar

Hazbar’s work is exhibited together with Erez Nevi Pana’s naturally-grown salt sculptures – ‘Crystalline’ (2020), and ‘Crystallization’ (2019) – and Lukas Wegwerth’s poetic ceramics that are colonised by crystal formations. Together, they remind us of the potential for designers to collaborate with natural systems.

Lukas Wegwerth, ‘Crystallization 152’, 2019

COURTESY: Lukas Wegwerth & NGV Triennial / PHOTOGRAPH: © Lukas Wegwerth & Gallery FUMI

Patricia Urquiola, ‘Recycled woollen island’, 2020

A striking proof of NGV’s landmark status among the local community is its Great Hall, which provides a hang-out spot for Melbournians under an elegant ceiling-covering glasswork by Australian artist Leonard French. Comfortable views of this colourful light-filled roof are offered by Patricia Urquiola’s mammoth size socks made from up-cycled felt in India. The Milan-based Spanish designer has long been an advocate of sustainability in design, and here, her statement also calls for relaxation and contemplation over twelve puffy lounges placed in pairs just beneath French’s grand work. The sock motif came to the designer when she noticed people take their shoes off to lie around the hall. The motivational or humorous slogans printed onto socks by fast fashion companies also urged Urquiola to utilise the blank canvas nature of her socks to add slogans relating to ethical production and recycling, as well as those that simply invite sitters to look up.

Installation view of Patricia Urquiola’s ‘Recycled woollen island’, 2020

COURTESY: Patricia Urquiola & NGV Triennial / PHOTOGRAPH: Tom Ross © Patricia Urquiola Studio, Milan

Cecilie Bendixen, ‘Cloud formations’, 2020

The museum collection is also the backdrop for Danish designer Cecilie Bendixen’s four radiant fabric clouds, suspended from the ceiling among Joseph Mallord William Turner’s romantic landscape paintings. These otherworldly light sources are less obviously utilitarian in their appearance, compared with Fred Wilson’s Murano glass chandelier, ‘To die upon a kiss’ (2011), which hangs in another classical art-filled gallery.

Fred Wilson, ‘To die upon a kiss’, 2011

COURTESY: Fred Wilson & NGV Triennial 2020 / PHOTOGRAPH: © Fred Wilson & Pace Gallery

However, similar to Wilson’s elegant embodiment of invisible African labour in 17th century Venice, Bendixen’s hand-stitched bulbous forms hide their labour-intensive manual process in their minimalist forms. The transience and ephemerality of a cloud, subtly comments on the overlooked human labour in the design industry today.

Cecilie Bendixen and her team creating ‘Cloud Formations’ collection in her studio, 2020

COURTESY: Cecilie Bendixen & NGV Triennial 2020 / PHOTOGRAPH: © Cecilie Bendixen