Noguchi

Bringing the work of the pioneering polymath to the wider attention of a European audience.

Barbican Art Gallery, London

30th September 2021 – 9th January 2022

Isamu Noguchi, ‘Akari’ models, 1953

COURTESY: ©INFGM / ARS – DACS / The Kagawa Museum

JAPANESE-AMERICAN sculptor Isamu Noguchi (1904-1988) is best-known for his iconic ‘Akari’ light, initially produced by Knoll Associates, and ‘Noguchi’ coffee table, manufactured by Herman Miller. But as an upcoming show at London’s Barbican Art Gallery will demonstrate, his work was wide-ranging, encompassing sculpture, painting, set design, industrial design, children’s playgrounds, landscape architecture and memorials.

Isamu Noguchi tests Slide Mantra at ‘Isamu Noguchi: What is Sculpture?’, 1986 Venice Biennale

COURTESY: The Noguchi Museum Archives, 144398 ©INFGM / ARS – DACS / PHOTOGRAPH: Michio Noguchi

The polymath disliked being labelled a designer. “I am not a designer,” he once affirmed. “The word ‘design’ implies catering to the quixotic fashion of the time. All my work – tables as well as sculptures – are conceived as fundamental problems of form that would best express [the] human and aesthetic activity involved with these objects.”

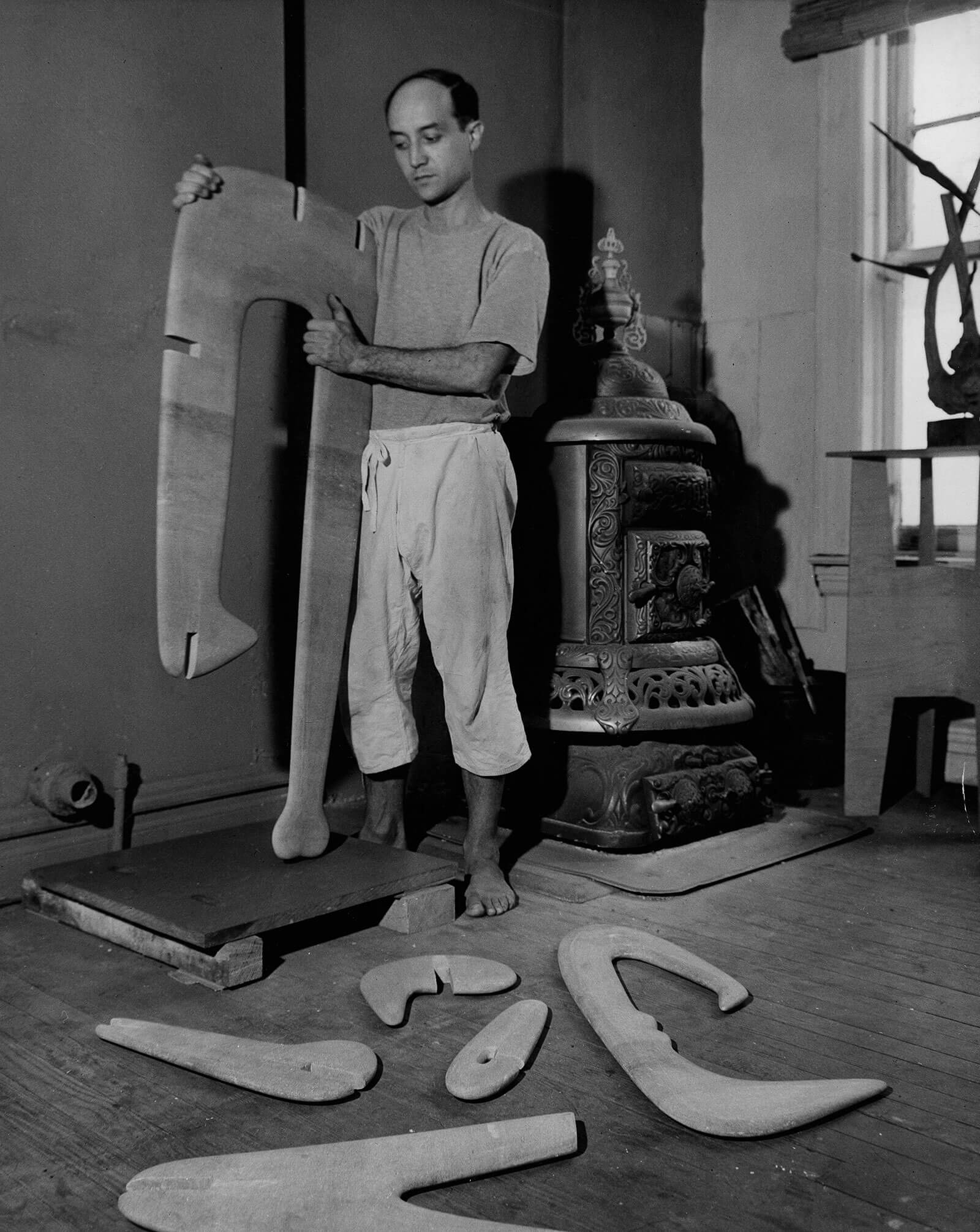

Isamu Noguchi assembling ‘Figure’ in his MacDougal Alley studio, 1944

COURTESY: The Noguchi Museum Archives, 03765 ©INFGM / ARS – DACS / Estate of Rudolph Burckhardt / PHOTOGRAPH: Rudolph Burckhardt

One reason for the exhibition is a growing interest in Noguchi’s work in Europe. Its pithy title – ‘Noguchi’ – suggests a familiarity with this multidisciplinary creative. Yet, despite belonging to a pantheon of celebrated mid-century designers, he has been under the radar here for decades.

“Noguchi has been underestimated,” says Florence Ostende, the show’s curator. “The Barbican has always wanted to do a retrospective on him. Other institutions felt the same way, namely Museum Ludwig in Cologne, Zentrum Paul Klee in Bern and LaM – Lille Métropole Musée d’art moderne, d’art contemporain and d’art brut – so we have joined forces with them to stage a touring exhibition.”

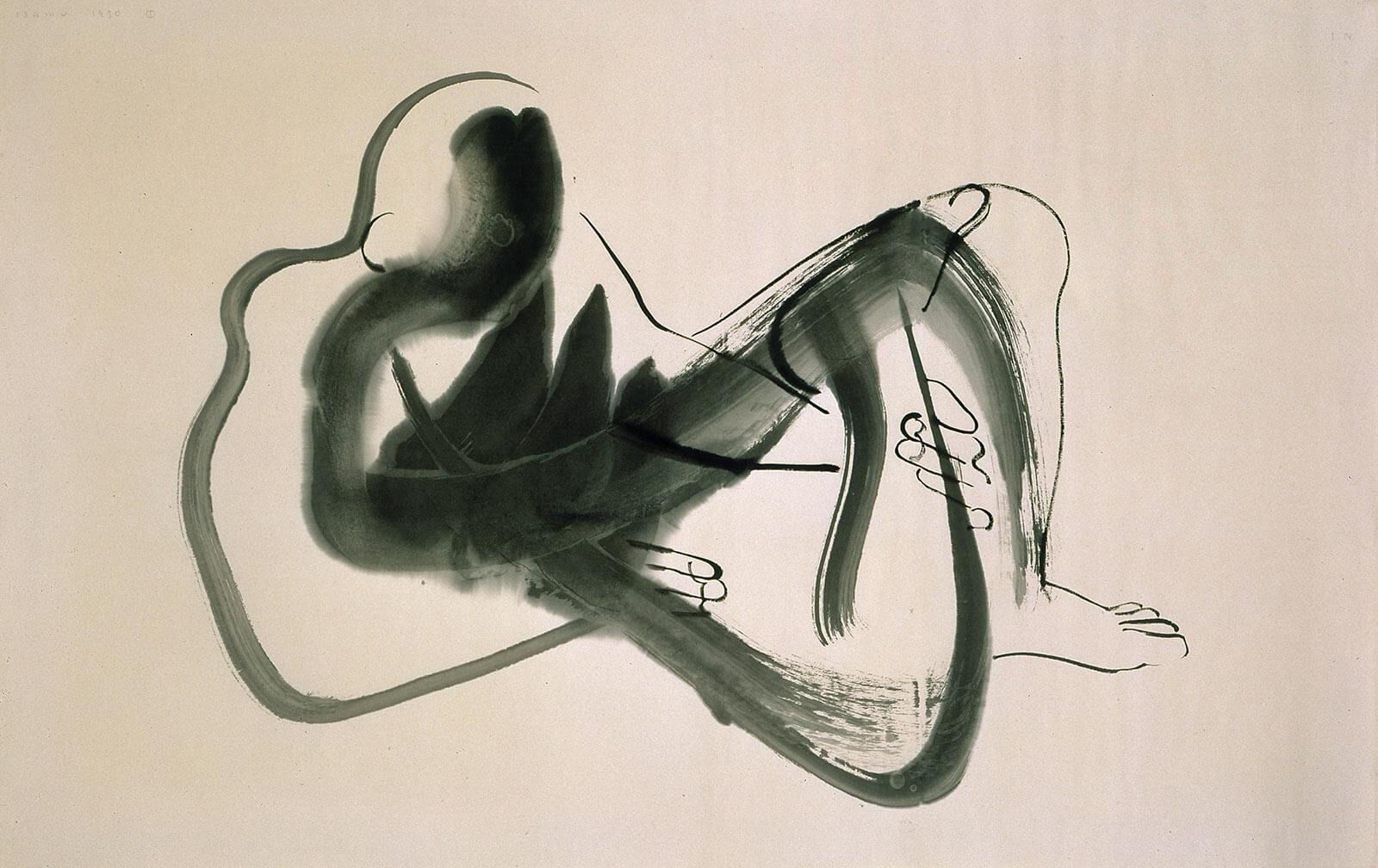

Isamu Noguchi, Peking Brush Drawing, 1930

COURTESY: The Noguchi Museum Archives, 01213 ©INFGM / ARS – DACS / PHOTOGRAPH: Kevin Noble

This brings together over 150 works, many lent by the Noguchi Museum in New York. “For years, Noguchi was better known in the US than in Europe, save for his ‘Akari’ lights, manufactured today by Vitra, and his set designs for choreographer Martha Graham,” says Dakin Hart, senior curator at the foundation. “He was a maverick, biracial, a globetrotter.”

Noguchi was born in Los Angeles to American writer and editor Léonie Gilmour and Japanese poet Yone Noguchi. His father ended the relationship with Gilmour before their son was born but, in 1906, he invited mother and son to visit him in Japan, only to cut ties with them soon after. From 1918, Noguchi went to school in Indiana, then attended Columbia University as a pre-medical student. In 1926, in New York, Noguchi, whose mother fostered his passion for art, saw a show of work by Romanian sculptor Constantin Brâncuși that inspired him to embrace modernism.

Isamu Noguchi, ‘Chess Table (IN-61)’, 1944

COURTESY: The Noguchi Museum Archives, 00856 ©INFGM / ARS – DACS / PHOTOGRAPH: Kevin Noble

In 1927, Noguchi was awarded a John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship to travel to Paris, where he worked as an assistant to Brâncuși. In the late 1920s and 1930s, with money earned from commissions for representational bronze busts – his bread and butter – he travelled to Asia, Mexico and Europe. In the 1940s, Noguchi began creating biomorphic sculptures influenced by Surrealist artist Jean Arp.

Isamu Noguchi, 1947

COURTESY: Getty Images / INFGM / ARS – DACS / PHOTOGRAPH: © Arnold Newman Collection

The Noguchi show has echoes of another Barbican exhibition curated in 2017 by Ostende, ‘The Japanese House: Architecture and Life after 1945’. Both were designed by Lucy Styles, and the Noguchi show promises to be very atmospheric, incorporating his illuminated, 1940s ‘Lunar’ sculptures – precursors of the ‘Akari’ lamps.

Isamu Noguchi, Lunar Infant, 1944

COURTESY: The Noguchi Museum Archives, 150797 ©INFGM / ARS – DACS / PHOTOGRAPH: Kevin Noble

Noguchi dreamed up the lamps after visiting the town of Gifu in Japan in 1951. Borrowing from its tradition of crafting parasols and lanterns from bamboo and washi paper derived from mulberry bark, he fashioned ‘Akari’ – which means light in Japanese – from the same materials. Its simple shade proved protean in his hands, assuming myriad forms, from Brâncuși-esque totemic structures to egg shapes and cubes. Flat-packed and easy to transport, ‘Akari’ was appealingly practical, too.

Isamu Noguchi, ‘Akari 25N’, 1968

COURTESY: The Noguchi Museum Archives, 03066 ©INFGM / ARS – DACS / PHOTOGRAPH: Kevin Noble

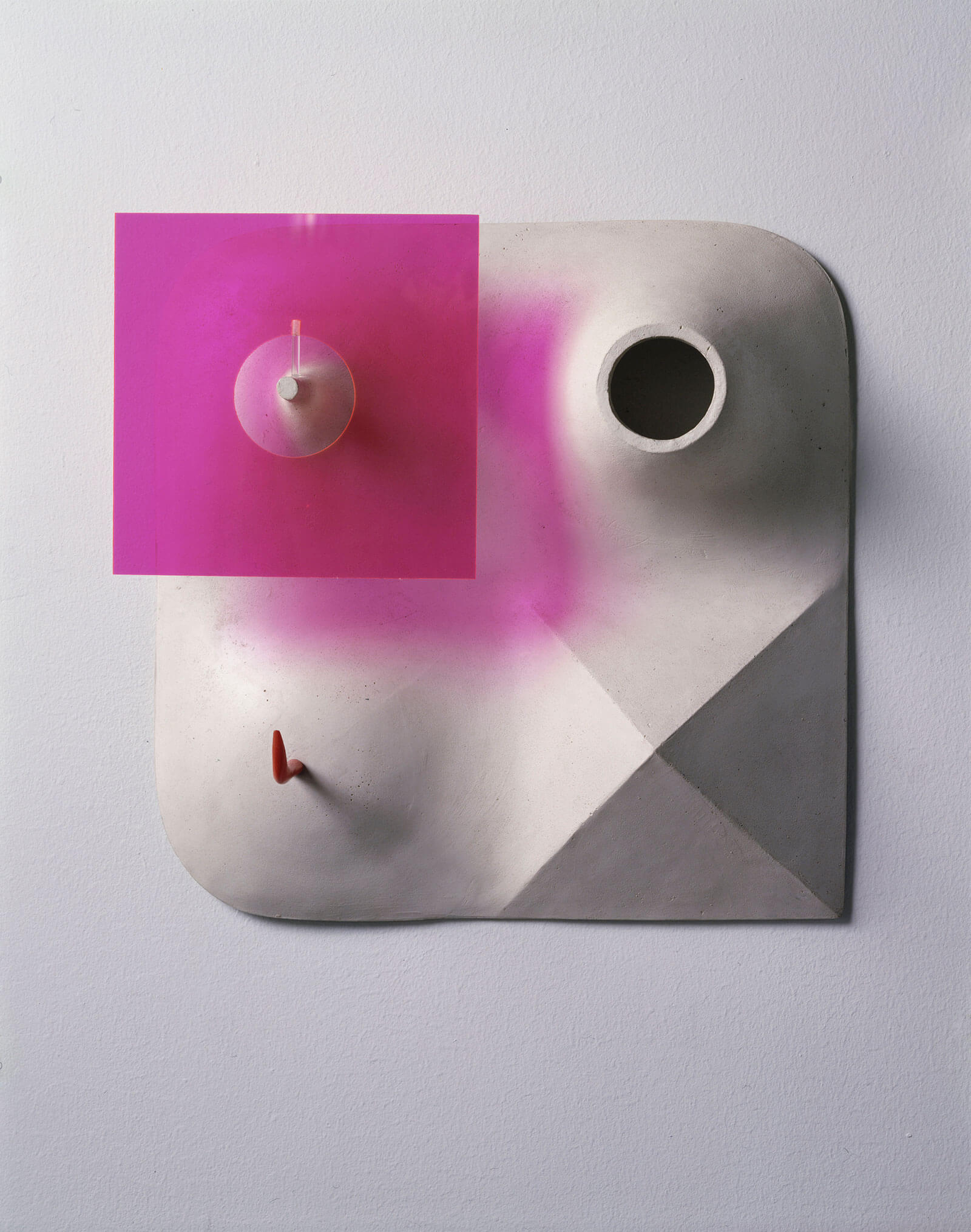

Noguchi’s mercurial approach was also reflected in his eagerness to experiment with other materials – wood, ceramics, marble, aluminium, steel and plexiglass. Almost as well-known as his ‘Akari’ lighting are his joyously ludic, often colourful playgrounds. He came to believe that sculpture should be tactile and interactive. Accordingly, his relatively compact sculptures eventually evolved into large-scale public projects – a seminal, albeit unrealised, example being his ‘Play Mountain’ of 1933. This mountain-shaped venue in Manhattan devoted to leisure would have boasted a pond, pool and facilities for skiing and swimming.

Isamu Noguchi, Octetra Play Equipment, Moerenuma Park, Japan

COURTESY: © Toshishige Mizoguchi / INFGM / ARS – DACS / PHOTOGRAPH: Toshishige Mizoguch

Noguchi’s multifaceted work was informed by his rapports with avant-garde figures. “The show looks into Noguchi’s interest in travel and his friendships, including with architect Buckminster Fuller,” says Ostende. Noguchi first met Fuller – and Graham – in 1929 at Romany Marie’s, a bohemian bistro-cum-salon in Greenwich Village, New York. Fuller had painted its walls silver. That year, Noguchi created a futuristic, chrome-plated bronze bust of Fuller. “Chrome-plating was a brand new technique used in the automotive industry,” says Ostende. “Like Fuller, Noguchi was interested then in technology, equating it with progress.” In 1937, Noguchi designed the streamlined ‘Radio Nurse’ with a Bakelite casing, the world’s first electronic baby monitor, manufactured by Zenith Radio Corporation.

Isamu Noguchi, manufactured by Zenith Radio Corp., ‘Radio Nurse’ and ‘Guardian Ear’, 1937

COURTESY: ©INFGM / ARS – DACS / PHOTOGRAPH: Kevin Noble

Noguchi was hugely prolific, despite facing much adversity. Not only was he rejected by his father but he experienced discrimination and racism. The attack on Pearl Harbour in 1941 triggered anti-Japanese prejudice in the US, resulting in many of its Japanese citizens being incarcerated. Although exempt from this, the following year he voluntarily entered an internment camp in Arizona where he proposed to design parks and recreational areas. It was a fiasco: the camp administrators regarded him as a troublemaker, while internees suspected him of conspiring with the administrators.

Isamu Noguchi, ‘My Arizona’ (second state with original elements), 1943

COURTESY: The Noguchi Museum Archives, 00071 ©INFGM / ARS – DACS / PHOTOGRAPH: Kevin Noble

His postwar projects included sets for many of Graham’s ballets, the Adele Rosenwald Levy Memorial Playground in New York, co-designed with architect Louis Kahn from 1961 to 1966, and his 1982 Memorial to the Dead in Hiroshima.

So why is the formerly unsung Noguchi widely admired today? “He is relevant because the white, macho male canon of art is being exploded, and his multidisciplinary approach is recognised as a prototype of contemporary art and design practices,” avers Hart. “Many in the design world now view him as a model, from Jasper Morrison to John Pawson.”

Isamu Noguchi in his 10th Street, Long Island City, Queens Studio, 1964

COURTESY: The Noguchi Museum Archives, 07281 ©2021 The Estate of Dan Budnik. All Rights Reserved / INFGM / ARS – DACS / PHOTOGRAPH: Dan Budnik