Paris Dispatch / November 2021

Depth, breadth and diversity – the highlights of collectible design this autumn.

OCTOBER IS ONE of the busiest months in the Paris art world calendar. FIAC, France’s international contemporary art fair, took place in the Grand Palais Ephémère, a temporary structure designed by the French architect Jean-Michel Wilmotte on the Champ de Mars, near the Eiffel Tower. Asia Now, a satellite fair, was held concurrently on Avenue Hoche which leads off the Arc de Triomphe. Meanwhile, Genius Loci, a new venture, saw works by artists and designers beautifully displayed in L’Ange Volant, a house designed by Gio Ponti in the 1920s. And galleries opened exhibitions on leading artists and design movements. The Design Edit reports on the month’s highlights.

Installation view, ‘Genius Loci’

COURTESY: Genius Loci / PHOTOGRAPH: © Jérémie Léon

FIAC and Asia Now

On a white oval table on Templon’s stand at Asia Now, hundreds of miniature interior objects were all meticulously entwined in criss-crossing red threads. Chiharu Shiota, the Japanese-born, Berlin-based artist made this incredibly intricate installation of tiny pieces of furniture, priced at €350,000, during pandemic lockdowns. Shiota, who represented Japan at the Venice Biennale in 2015, usually fills gallery spaces with immersive, floor-to-ceiling, site-specific sculptural works. Unable to travel during the pandemic, she switched her focus to a shrunken scale and dwelled on the contents of people’s homes.

Chiharu Shiota, ‘Living Inside’, 2021

COURTESY: Chiharu Shiota / PHOTOGRAPH: Tanguy Beurdeley

Nearby, Perrotin was unveiling exquisite tapestries made by Aya Takano in collaboration with weavers in Nepal. Marking her first foray into tapestry, they are based on Takano’s manga-inspired drawings of young girls surrounded by animals – snow leopards in one, a bird and a dog in another.

Aya Takano, ‘Himalayan monal, rhododendron, festival of dog, chatpate’ Nepalese rug, 2020

COURTESY: Aya Takano

Over the Seine at big sister fair FIAC, the design sector brought together five galleries: Jousse Entreprise, Laffanour – Galerie Downtown, Galerie Kreo, Eric Philippe and Patrick Seguin. With works by designers from Jean Prouvé to Pierre Paulin, Hella Jongerius and Jaime Hayon, each gallery presented an introduction to its programme.

Functional art was spotted at several other stands. Bel Ami from Los Angeles sold several ceramics, priced €4,300, from Soshiro Matsubara’s ‘Last Night’ series (2021). The Japanese-born, Vienna-based artist has taken the idea that Medusa in Greek mythology could turn anyone she looked at into stone – and created these humorous, ornamental wall lamps with female faces in between serpentine forms.

Soshiro Matsubara, ‘Last Night XXIX’, 2021

COURTESY: Soshiro Matsubara & Bel Ami Los Angeles

And Galerie In Situ-Fabienne Leclerc had a solo show by the Iranian trio Ramin Haerizadeh, Rokni Haerizadeh and Hesam Rahmanian, who interweaved ideas about news events, politics and cuisine in a multi-media installation. In the centre of the booth was a dining table and four stools, whose surfaces combined images of extraction towers and the artists’ hairy chests. It was just one of the many eclectic offerings at FIAC.

Ramin Haerizadeh, Rokni Haerizadeh, Hesam Rahmanian, ‘O You People!’, 2021

COURTESY: Galerie In Situ- Fabienne Leclerc / PHOTOGRAPH: ©Aurélien Mole

Genius Loci

The renowned Italian architect and designer Gio Ponti designed only one house in France during his career: L’Ange Volant – meaning the winged angel – in a smart suburb west of Paris near the Longchamp racecourse. This neo-classical gem was built in 1927 for Tony Bouilhet, then director of the glass manufacturer Christofle, whose family still owns it today. An angel is carved into a circle above the front door. Beyond it, Ponti has played with alcoves, arches and volumes and adorned the high ceiling in the living room with blue, white and pale yellow patterns.

Installation view, ‘Genius Loci’

COURTESY: Genius Loci / PHOTOGRAPH: © Jérémie Léon

Within this glorious setting, the curator and journalist Marion Vignal launched a selling exhibition of more than 30 works, some of them special commissions, during FIAC. The galleries Kamel Mennour, Perrotin, Armel Soyer, Nilufar and Galerie Italienne loaned works by their artists and designers, others came directly from artists’ studios. This juxtaposition of Ponti’s oeuvre with contemporary creatives recalls how Ponti promoted emerging names in Domus, the magazine he launched in 1928.

Vignal’s discerning selection blended beautifully with Ponti’s vision. In front of the living room fireplace, Julian Mayor’s ‘Jagged Edge’ sculptural table in welded steel reflected Ponti’s sky blue armchairs made for the first class compartment of the ETR 300 ‘Settebello’ train.

Gio Ponti, pair of armchairs made for the First Class carriages of the ETR 300 ‘Settebello’ train, circa 1952; Julian Mayor, ‘Jagged Edge’ sculpture, 2021

COURTESY: Nilufar Gallery & Galerie Armel Soyer / PHOTOGRAPH: © Jérémie Léon

Several pieces played with transparency. Below the balustrade staircase were Studio Nucleo’s ‘Color Lenses’ (2020) red epoxy resin bench with bronze legs and ‘Crossette Lamp’ (2017) by Michael Anastassiades, with bulbs at the descending tips of red looped branches.

In the dining room, extending off the living room, Ponti’s letters with drawings on them were encased between the glass sheets of Studio KO’s dining table. Ponti’s tin candlestick (edited by Christofle in 1927) and Damian O’Sullivan’s elegant aluminium-and-brass candlesticks and earthenware vase decorated the table’s surface. At the end of the room, Roberto Giulio Rida’s ‘Pistolini’ cabinet (2018), in purple glass dotted with green crystals, contributed to the play on reflections.

Roberto Giulio Rida, ‘Pistolini’ cabinet, 2018

COURTESY: Nilufar Gallery /PHOTOGRAPH: © Jérémie Léon

The exhibition continued upstairs in the blue and yellow bedrooms. Laurent Grasso’s enigmatic ‘Spectral Ponti’ (2021) video, based on a scan of the property, showed black-and-white spectral silhouettes devoid of furniture. It was presented on screens on Ponti’s desks.

Then outside, lying on the lawn of the garden, was Mathias Kiss’s ‘90 degrés Sky Mirror’ (2021). Based on the herringbone patterns of Haussmannian wooden floorboards, the symmetrical design reflected fragmentations of the house, grass and surrounding trees, depending on the viewer’s standpoint. Overall, it was a stunningly curated show that revived Ponti’s love of storytelling in his projects.

Mathias Kiss, ‘Sky-Sans 90 Degrés’, 2021

COURTESY: Mathias Kiss

Latin American Modernism: From Architecture to Design at Laffanour – Galerie Downtown

François Laffanour has transformed his gallery into a colourful Luis Barragán house, the walls painted pink, yellow, blue and green, with drawings, palm plants and ivy adding to the vibrant atmosphere. This homage to Casa Barragán, which was Barragán’s house in a suburb of Mexico City, sets the tone for the exhibition on Latin American modernist design created after the Second World War.

Zanine Caldas, (foreground) ‘Denucia’ round table, 1970-1979; (background) ‘Bench’, 1975

COURTESY: LAFFANOUR – Galerie Downtown

Laffanour has focused on three luminaries from that era: Barragán, who was Mexican, alongside two Brazilians: Oscar Niemeyer and José Zanine Caldas.

All three were architects who also designed furniture. Both Barragán and Niemeyer won the prestigious Pritzker Architecture Prize, in 1980 and 1988 respectively, and were inspired by Le Corbusier. Barragán developed a functionalist, geometric style through commissions for private houses and primarily created furniture for these residential projects. Meanwhile, Niemeyer designed an iconic cathedral and other edifices for Brasília, which became the new Brazilian capital, as well as furniture to accompany the interiors. For his part, Zaldas, who hailed from Bahia in the north of Brazil, had environmental concerns about forests and sought to use felled trees whenever possible.

Zanine Caldas, ‘Armchair’, 1975

COURTESY: LAFFANOUR – Galerie Downtown

Their different approaches to furniture can be perceived in this exhibition. Barragán’s rectilinear ‘Cuadra San Cristobal’ pine cabinet, bench and dressing table from the 1950s-1960s contrast with Zaldas’s beautifully carved, curvilinear armchairs and sofa made from pequi wood in the 1970s.

Luis Barragán, ‘Cuadra San Cristobal’ sideboard, 1966-1968

COURTESY: LAFFANOUR – Galerie Downtown

Within this orchestrated mise-en-scène, Niemeyer’s low square glass-and-wood table from 2007 has a slightly dissonant ring, somehow seeming too slick, too modern. It was created several decades after Niemeyer went into exile in France in the 1960s following Brazil’s military dictatorship. (Niemeyer, a lifelong communist, designed the headquarters of the French communist party, among other projects.) Apart from this off-key note, Laffanour has brought the trio of talents together with panache.

Alighiero Boetti: Thinking about Afghanistan at Tornabuoni

In March 1971, the Italian artist Alighiero Boetti, then 30 years of age, embarked on his first trip to Afghanistan. By then, he had become one of the prominent Arte Povera artists, making works with modest, everyday materials. Germano Celant, the critic who coined the term Arte Povera, had included Boetti in all his group shows.

Curious about other cultures, geography and a non-authorial approach to making art, Boetti sought to distance himself from Arte Povera and invent a more conceptual language. His interest in Islamic culture was connected to how an eighteenth-century Dominican monk ancestor had converted to Islam on a mission to Constantinople and become a leader of the Chechen people against Russia’s Catherine the Great.

Alighiero Boetti, ‘Mappa’, 1983

COURTESY: Tornabuoni Art

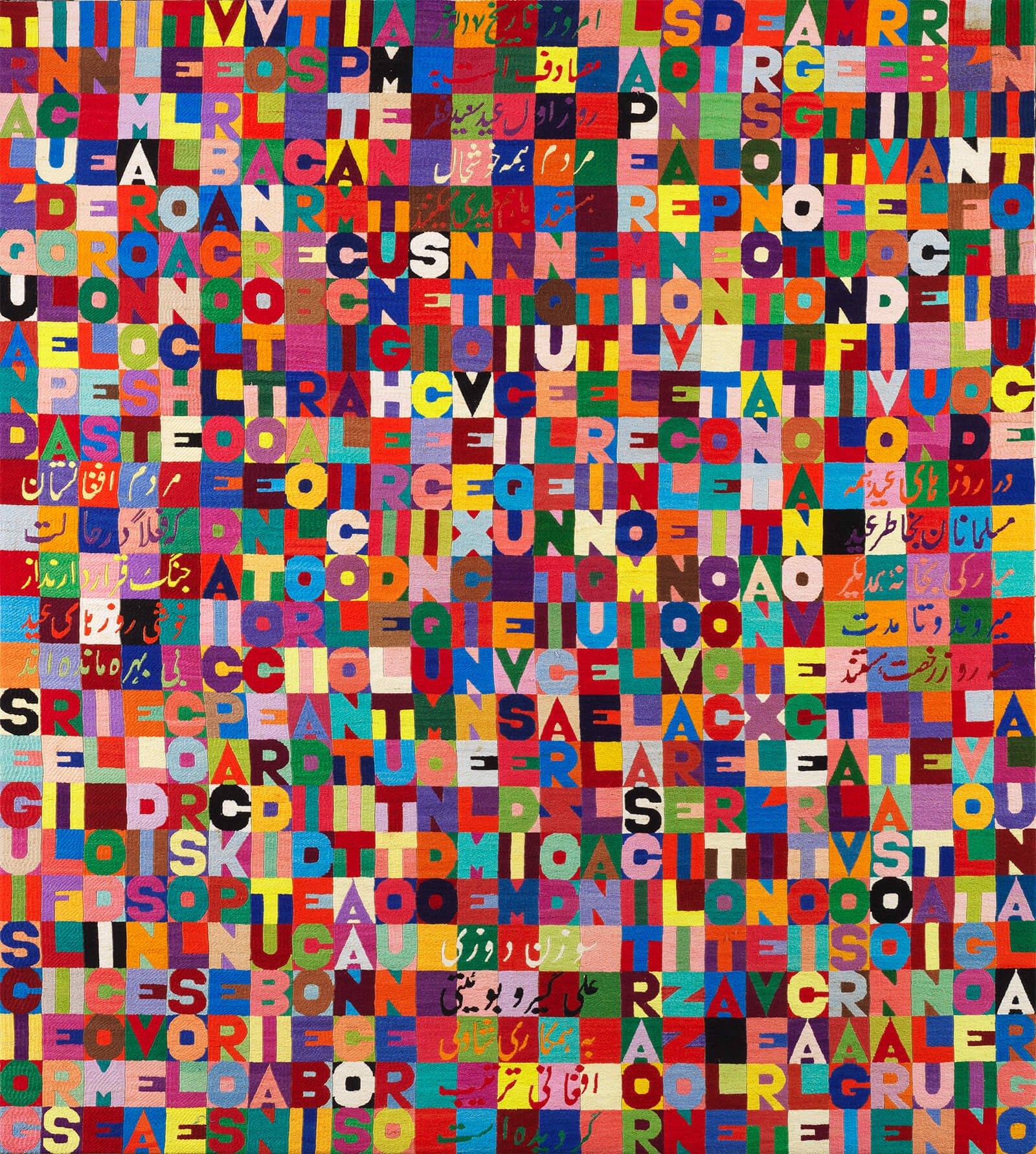

Boetti’s first trip to Afghanistan – when the country was on the hippie trail along with Nepal – was the start of a long relationship with its people. In autumn 1971, Boetti returned to Kabul and opened the One Hotel, an eleven-room hotel (he would occupy room 11 during his visits) with the help of Ghulam Dastaghir, who became its manager. Dastaghir found Afghan women to embroider artworks for Boetti, who would take over canvases that were prepared with outlines and designated colours. These culminated in ‘Mappa’ tapestries (world maps showing countries’ national flags, relating to the global geopolitical situation of the time); gridded “word squares” revealing his love of word play, and ‘Tutto’ tapestries of interlocking objects, hands and shapes, representing “everything” in society. Following the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, Boetti had his works embroidered by Afghan women, who had fled to Peshawar in Pakistan, until his death in 1994.

Alighiero Boetti, ‘Senza titolo (Tra l’incudine e il martello…)’, 1989

COURTESY: Tornabuoni Art

Tornabuoni’s show marvellously brings together embroidered works along with photos and letters from Boetti’s trips to Afghanistan that bear testimony to his affection for the land and its people.

Sheila Hicks: Grace, No Gridlock at Galerie Frank Elbaz

The title of Sheila Hicks’s exhibition alludes to her creative equanimity during pandemic lockdowns. The joyous centrepiece, ‘En route vers Séville’ (2021), a cascade of yarns, braids and ribbons in a palette of gold, orange, brown and grey tumbling onto the floor, was created in situ. It is surrounded by a diversity of works, such as a mound of white balls evocative of stones.

Sheila Hicks, ‘Grace, No Gridlock’ exhibition view, 2021

COURTESY: Sheila Hicks / PHOTOGRAPH: Claire Dorn

The 87-year-old American artist has been based in Paris since 1964 and was honoured with a retrospective of her pioneering artworks at the Centre Pompidou in 2018. She became interested in weaving and fibres in South America after receiving a Fulbright scholarship following her MFA at Yale University, where she studied under Josef Albers. The timing of her show coincides with the exhibition about Anni and Josef Albers at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris.

Hicks’s versatility is firmly on display. Besides geometric linen works that Hicks regards as abstract paintings and bear the influence of the Bauhaus are a bunch of brightly coloured batons and circular fabric pieces tightly bound by intersecting threads.

Sheila Hicks, ‘Grace, No Gridlock’ exhibition view, 2021

COURTESY: Sheila Hicks / PHOTOGRAPH: Claire Dorn

What’s also striking is her collaboration with the fashion photographer Paolo Roversi, who has photographed her sculptures. In turn, Hicks has embellished his dreamy image of a model in a gown with wavy threads and fibres and scattered fibres onto the wall around it, expanding the field of the frame.

Sheila Hicks, ‘Roversi Paolo’, 2021

COURTESY: Sheila Hicks / PHOTOGRAPH: Claire Dorn

More of Hicks’s embellishments of Roversi’s work are showcased in an altar-like space at Galerie Zlotoski, which is located in the St-Germain-des-Prés district where Hicks lives. Over 40 small-scale weavings, titled ‘Minimes’ made during the pandemic are also presented. Shells are embedded into some of these pieces, which bring beaches, forests and landscapes to mind and capture Hicks’s desire to reconnect with nature.

Genius Loci at L’Ange Volant, 16th– 24th October 2021.

‘Latin American Modernism: From Architecture to Design’ is at Laffanour – Galerie Downtown, 18 rue de Seine, 75006 Paris, until 11th November 2021.

‘Alighiero Boetti: Thinking about Afghanistan’, is at Tornabuoni, 16 Avenue Matignon, 75008 Paris, until 22nd December 2021.

‘Sheila Hicks: Grace, No Gridlock’ is at Galerie Frank Elbaz, 66 rue de Turenne, 75003 Paris, until January 2022. Prices: $18,000-$280,000.