Noro Khachatryan

The Armenian-Belgian designer sets up shop in Brussels's up-and-coming Molenbeek neighbourhood.

New office area

COURTESY: Studio Khachatryan

BRUSSELS HAS A complicated identity. Straddling a contested linguistic and cultural border, the Belgian capital also serves as the seat of the European Union and numerous other international organisations. Its 19 tiny municipalities weave together in an, at times, dysfunctional jumble of different architectural styles, convoluted histories, political inconsistencies and economic disparities.

Because the medium-sized city sits at the intersection of boisterous metropolises like London, Paris, Amsterdam and Frankfurt, it is often overlooked and quickly written off as a humdrum bureaucratic backwater beleaguered by mismanagement, filth and criminality. For many, it seems simple enough to ignore Brussels when travelling through on the Thalys train, or on a tour to medieval Disney Worlds like Bruges. Their loss.

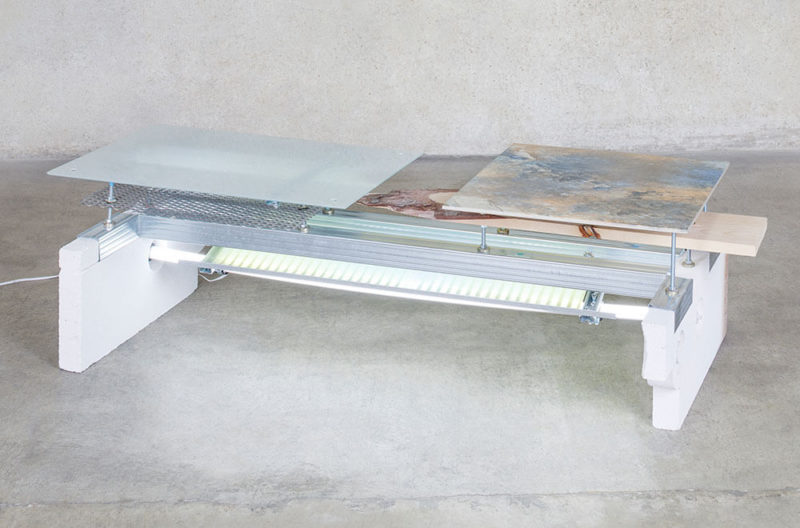

Studio Khachatryan, ‘If’ side tables, 2016

COURTESY: Studio Khachatryan

This existential messiness has afforded the capital with a collective sense of unpretentious receptivity and acceptance. Drawn in by a relatively flat rate of gentrification, inexpensive rents, urban grittiness and strong transportation links, creatives have flocked to the city over the past few decades. Prominent international galleries have followed suit by establishing important outposts and fostering an ever-growing art scene. Centre Pompidou’s opening of the experimental kunsthalle-style KANAL in an old Citroën garage in 2018 marked an important milestone. New events like the Collectible Fair and venues like the ADAM (Design Museum Brussels) have piggybacked on the expansion of an equally dynamic design scene in recent years. For a long time, this rich cultural tapestry, intermixing the old with the new and the low with the high, centred around Brussels’s more affluent central, eastern and south-eastern districts.

However, in just the past year or two, a few trailblazers have ventured across the city’s canal into more impoverished western neighbourhoods – like Molenbeek. This area gained international attention in 2015 as the base for Islamist terrorists who carried out attacks in France and Belgium. Shaking off the stigmas of this so-called ‘no-go’ zone to uncover a vibrantly diverse community hasn’t been easy.

-

Studio Khachatryan, ‘C.19.1’ chair, edition (a), solid aluminium, 2019

COURTESY: Studio Khachatryan

-

Studio Khachatryan, ‘C.19.1’ chair, edition (b), solid bronze, 2019

COURTESY: Studio Khachatryan

“I was worried about this reputation at first and if my clients would be willing to visit me,” Noro Khachatryan explains.” But given the proximity to the city centre, it made sense to open a studio here.” The Armenian-Belgian designer teamed up with American-born gallerist Harlan Levey and his Chinese-Belgian partner Winnie Kwok to acquire and transform a former factory into a shared gallery and studio complex. “We all arrived in Belgium at the same time 20 years ago and have since become very close. I’ve been living in Mechelen for most of that time and could never afford the type of space I would need in Brussels on my own. Winnie had the idea of pooling our resources and finding something together. We visited 20 different locations and finally discovered this building. It took some persuading from Harlan to come to Molenbeek, but now I’m very pleased we did.”

Noro Khachatryan

COURTESY: Studio Khachatryan

Featuring a double-height exhibition hall below for Harlan Levey Projects’ ground-breaking shows and Khachatryan’s workshop in a loft above, the 440-square-meters complex was completely refurbished by the designer during an intensive two-year period. Completed earlier this month, the project stands as a testament to his minimalistic and mathematically inspired aesthetic. “I didn’t want to make a crazy statement but rather keep the industrial rawness of the space,” the designer explains. “For me, luxury can be achieved with low-budget materials that are durable. The walls we painted in white are made out of cement and will last a long time. It’s simple but effective.”

First constructed in the 1890s, the building underwent various renovations over the years, but Khachatryan unified the different elements by reviving certain features and introducing others. A central switch-back welded staircase that links to the two programs is sturdy and functional and, because of that, has a bold aesthetic presence. Other than a fresh coat of paint, some parts were left untouched. “I decided to install 32 thousand tiny rectangular tiles in my studio to create continuity,” he admits. “Because of Covid and a limited budget, I ended up installing them myself.” These textured brick-like elements tie together a sectioned-off office, a workshop and a streamlined kitchen. In Belgium, Khachatryan is mainly known for his highly sculptural furnishings but not his interior projects, primarily developed in the Middle East. He hopes that the overall complex will serve as a calling card in that respect.

Studio Khachatryan, ‘Kep t’ table, 2018

COURTESY: Studio Khachatryan

The upstairs studio is also intended to act as an impromptu showroom for Khachatryan’s object designs. “There is no such thing as a showroom in my mind,” he describes. “I’m inspired by how Brancusi set up his Paris atelier. Works in progress were already put on display and could be refined over time. I try to do the same and present my pieces in a way that’s pleasing to my own eyes.”

This holistic approach will allow Khachatryan to sell works directly from his studio if needed, but not run his own gallery per se. He will exchange furnishings and works of art with Levey so that each can complete their own floors and, in turn, tie the entire complex together, set to open on 22nd April.