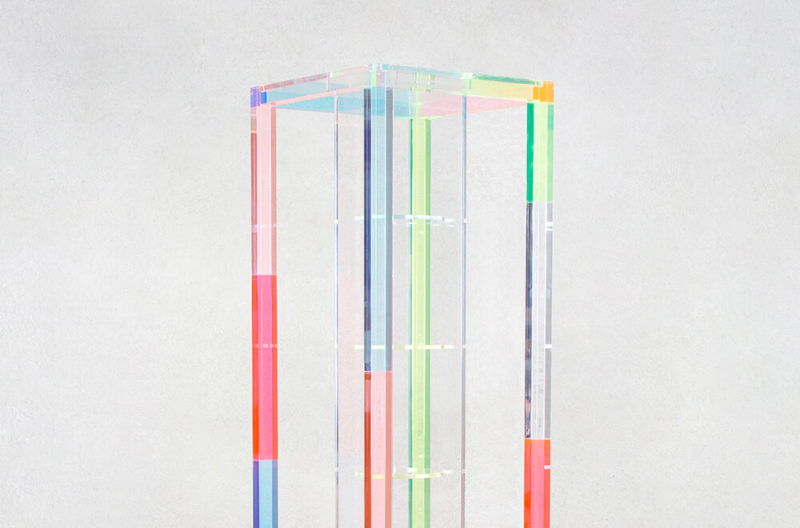

‘Ginza Robot’ cabinet, 1982

Masanori Umeda

Masanori Umeda for Memphis, ‘Ginza Robot’ cabinet, 1982

COURTESY: Gift of Collab: The Group for Modern and Contemporary Design at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, in memory of Hava J. Krasniansky Gelblum, 1994

THIS PATCHWORK COMPOSITION is emblematic of everything the postmodern Memphis movement represented. A geometric totem wrapped in surface-level plastic laminated chipboard, it is both a celebration and critique of the rampant consumption and excesses of the 1980s. In line with this paradoxical framework – one inspired by the poststructuralist philosophies of Jacques Derrida and Gilles Deleuze put forward a decade earlier – this work riffs on the semiotic visual and anthropomorphic vocabulary of space-age robots. However, its bombastic angular protrusions are also reflective of the era’s preoccupation with fleeting styles and its refutation of formal cohesion. Ironically, the Memphis movement, for all its throwaway exuberance, was revived, and had a lasting impact on 21st century design.

“Memphis designers are hardly sharp-tongued intellectuals or prophets obsessed by a redeeming message that will save the world,” one of the group’s founding members, design critic Barbara Radice, once described. “Compared with the leaders of the previous generation they’re curious, optimistic, eclectic, a bit superficial, a bit nonchalant, enthusiastic in a rather insolent way. They are great fans of the mass media, fashion devourers, hamburger eaters, record collectors.”

‘Ginza Robot’ cabinet was designed by maverick talent Masanori Umeda in 1982, soon after returning to his native Japan, and refers to the country’s popular culture. The form of this storage unit refers to the mechanical men of Japan’s science fiction and the popular toys they inspired. The cabinet is named ironically after Tokyo’s most fashionable shopping district. It contains some shelving components but is primarily presented as a statement piece, not a functional furnishing.

Born in 1941, Masanori trained at Tokyo’s Kuwasawa School of Design. In 1967, he moved to Milan and quickly immersed himself in the radical design zeitgeist that was shaping Italian design at the time. He initially worked for Achille and Pier Giacomo Castiglioni, before becoming a design consultant for manufacturer Olivetti. During this time, he came into close contact with Memphis’s founder Ettore Sottsass and many of the noted designers that defined this movement. For much of the 1980s, his increasingly extravagant works were crafted by Memphis Milano, the production wing of the collective. Perhaps most recognised of these pieces was the 1981 ‘Tawaraya Ring’ bed, coalescing symbolic elements of a boxing ring and a traditional Japanese bedroom.

One of the few ‘Ginza Robot’ cabinets ever produced was recently acquired by the Brooklyn Museum in New York, as part of its redesigned decorative arts galleries opening this autumn. Inaugurating this new wing is the ‘Design: 1880 to Now’ exhibition mounted by Design Miami curatorial director Aric Chen in honour of the late Dr Barry R. Harwood, curator of Decorative Arts at the museum from 1988 to 2018. This permanent survey show seeks to reimagine the collection and look beyond traditional Eurocentric narratives.

Installation view, Design 1880 to Now, Brooklyn Museum

COURTESY: Brooklyn Museum / PHOTOGRAPH: Jonathan Dorado

As part of this new display, the Japanese Modern section addresses how this country explored and adopted modernism in its own distinct way. Japan’s ongoing industrialisation and modernisation during the 20th century prompted a reappraisal of simple handicrafts. The country’s designers adopted a hybrid approach adapting new ideas and forms while using traditional materials and techniques. Mingei (folk crafts), which continue today, was highly influential in its advocacy of humble, anonymously crafted objects made for everyday use. This philosophy translated perfectly into the core tenets of modernism: an honest and simple design methodology. Umeda was no different in his early days but like most postmodernists, ultimately challenged these principles.