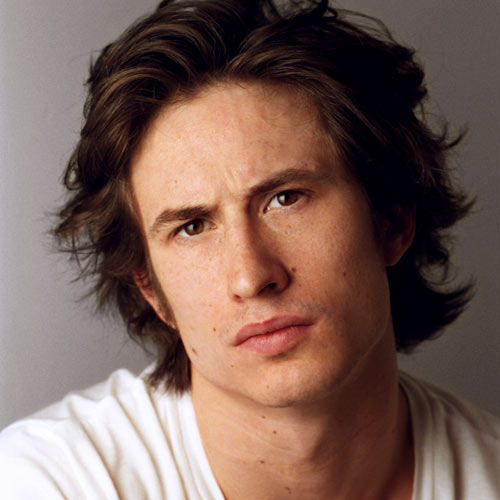

Casey McCafferty

From a family of masons, he gravitated towards wood where his sculptural skills and bold imagination have put him at the forefront of the contemporary Studio Craft Movement.

Casey McCafferty, ‘Reach Out’, 2021

COURTESY: Casey McCafferty / PHOTOGRAPH: Joseph Kramm

CASEY MCCAFFERTY HAS a powerful distaste for email. This is why, on occasion, he has found himself telling clients about the office assistant he doesn’t have – the one he fires when it becomes necessary to pass on the blame for unanswered messages. His skills at dissembling may be growing rusty of late, however, as a relationship with Gallery FUMI has added a layer of insulation between himself and needy buyers. This has surely afforded him even more time to develop his formidable skills as a sculptor.

Casey McCafferty

COURTESY: Casey McCafferty / PHOTOGRAPH: Joseph Kramm

Stacked lamination, McCafferty’s method of choice, has a venerable place in the history of American Studio Furniture. It was the signature of one the movement’s earliest leaders, Wharton Esherick, and also the favoured technique of its second-generation hero, Wendell Castle. The challenge for woodworkers has always been overcoming the tendency of wood to warp. Warp causes cracking, buckling, and delaminating; it prevents the easy relationship of wood with other materials such as stone, glass, and metal; and generally, it causes woodworkers to lose sleep and hair. The world, as we come to it, is rarely flat, straight, or smooth. So, in defiance of that, for many disciplines polished linearity has long been a default signal of craft mastery.

All this served to make the American Studio Movement, which began around the time of the Second World War, especially exciting as an alternative to the elegant but orthographic constructions of modernism. Castle and company created an upwelling of generously proportioned forms with sweeping contours, polished smoothness, and few formal precedents besides Antoni Gaudi. To the toolset of the traditional joiner these artisans added that least precise tool, the chainsaw. Stacked lamination provided them with the monolithic masses to plunge their blades into and gave wood a freedom of depth more commonly associated with marble.

Casey McCafferty, various works

COURTESY: Casey McCafferty / PHOTOGRAPH: Joseph Kramm

From their studios, polished, smooth forms flowed out – forms which the American public could appreciate for signalling craft mastery despite the daring newness of their morphology. Of that early American Studio cohort – J.B. Blunk, Wharton Esherick, Wendell Castle, Jack Rogers Hopkins, and Sam Maloof, only Michael Coffee, 93, remains working today, at least as recently as four years ago, when I briefly met him.

What does Casey McCafferty add to this tradition? He has eradicated the saccharine art-nouveau prettiness of earlier stacked lamination masters and in its place substituted a rewarding unpredictability. He has brought the technique in sync with the times – which favours the ungainly and awkward, the humorous and heterogenous rather than the placid and organised, the balanced and poised. Increasingly, he is charging his forms with psychic allusions and narrative energy.

‘Power of Myth’ in progress

COURTESY: Casey McCafferty / PHOTOGRAPH: Joseph Kramm

McCafferty comes from a family of masons. And yet he began his career by falling in love with wood. His progression from 2016, when he and everyone else on earth was busy making slab tables, to his breakthrough in 2018 when he produced his first “sculptural series” side table, has been meteoric.

To better understand just how it took place, I visited him in his new studio this August. As we talked, the intermittent whine of a planer undergoing repairs filled in the soundscape. We walked through an awesomely dusty machine room to a plastic tarp, which served as a door to a smaller space. “I try to keep the dust contained in this room,” he told me, as we passed the threshold of the carving room. Inside, among knee high piles of dust, I noted that people who do not spend their days in woodshops may have difficulty imagining what “contained” means for McCafferty.

Casey McCafferty’s studio

COURTESY: Casey McCafferty / PHOTOGRAPH: Joseph Kramm

He began woodworking in college, where he studied business. After a brief stint in a bank, he spent five years in LA building custom furniture for architects and interior designers. As that business grew, he found himself less and less directly involved with the making – “I was coming into the shop just to make sure things were getting done and going out for meetings. It got so far away from why I even started doing it,” he said to me. And so he dissolved that business to focus on making his own line of designs. A few years into that trajectory, he wearied of reproducing identical pieces to fill orders. In his off-hours, he began carving small sculptural objects. One such object became a table that seemed, part way through it’s making, to suddenly annihilate all the precepts of the Danish Modern-inflected work he had been designing. One leg of the table appeared abruptly swollen, like a kink in a balloon dog’s tail.

Assorted work including: (right) ‘Lighting Structure with a Seat’, 2020; (left) ‘Pomo Chair’, 2019

COURTESY: Casey McCafferty / PHOTOGRAPH: Joseph Kramm

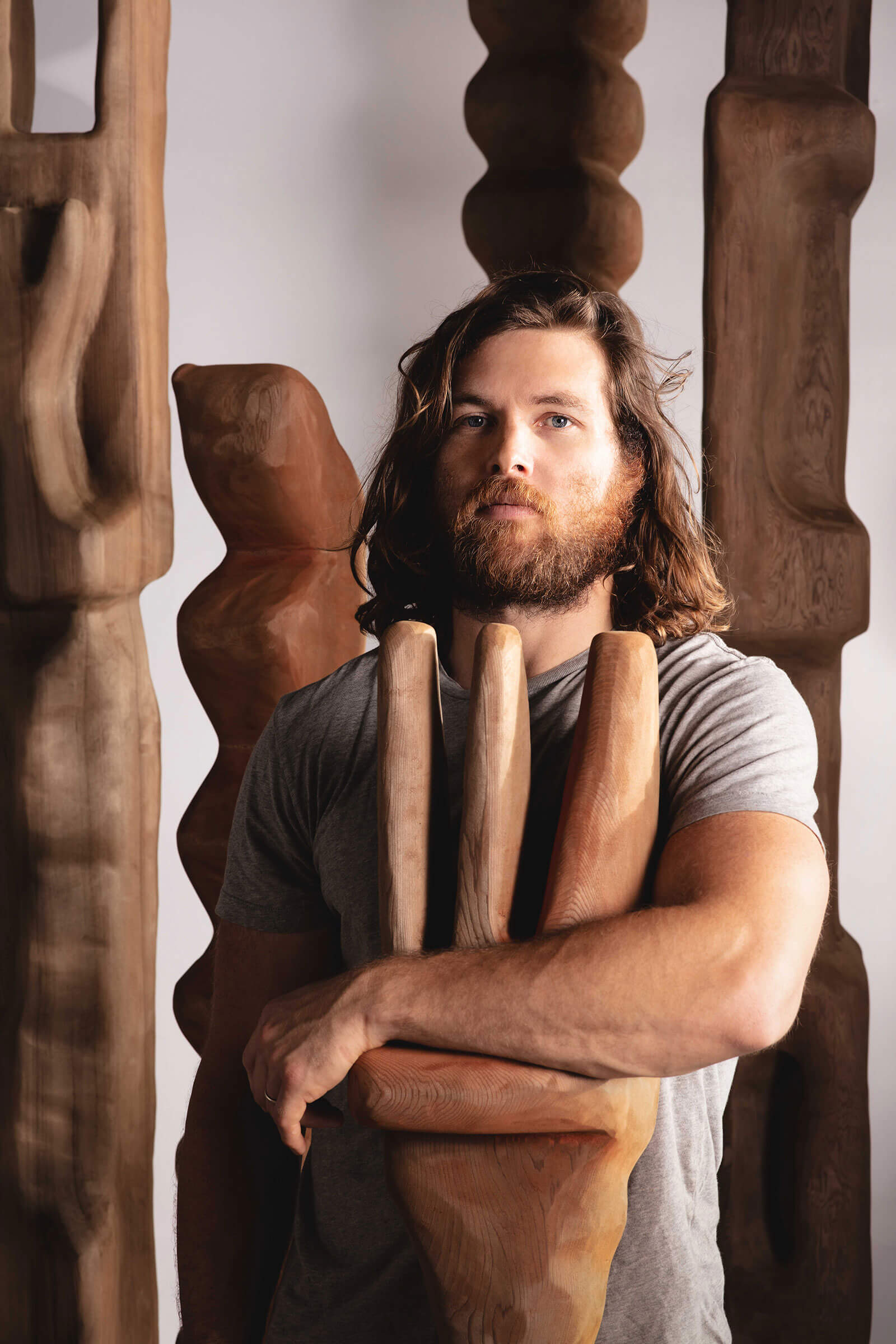

It’s three years later, and McCafferty is a bonafide connoisseur of the bulge. Sudden protuberances interrupt the flow of his forms. Recently, he has begun to explore explicit figuration. Hands reach out askance, arms jut at acute angles, noses emerge from planes with something of the hieroglyphic energy of the late Bay Area artist Jeremy Anderson. Several of his recent ‘Power of Myth’ totems are standing in the shop, rising precipitously overhead; indeterminate signpost of hands gesturing, pointing, entreating.

Casey McCafferty, ‘Power of Myth 2’ sculpture, 2021

COURTESY: Casey McCafferty / PHOTOGRAPH: Joseph Kramm

Casey

“Recently, McCafferty has begun to explore explicit figuration …”

McCafferty, ‘Power of Myth’ sculptures, 2021

COURTESY: Casey McCafferty / PHOTOGRAPH: Joseph Kramm

“… Hands reach out askance, arms jut at acute angles and noses emerge from planes”

The works bear some formal relation to oceanic art, however many of McCafferty’s allusions are nearer afield. When his first son went through “a period of being obsessed with hammers”, hammerlike shapes began to appear in McCafferty’s work. “I don’t want it to become so personal to me that it loses its accessibility to other people,” he says. Nonetheless, when prodded he acknowledges possessing a fund of highly specific meanings and associations for most of his formal vocabulary. New materials have begun appearing in his shop, in particular stone, which he tends to leave rough with claw chisel marks forming striated hatch patterns on the surface.

‘Reach Out’, 2021, in progress

COURTESY: Casey McCafferty / PHOTOGRAPH: Joseph Kramm

McCafferty’s peers include a number of artist-designers advancing stacked lamination into new territories. Vincent Pocsik has given the technique a technological update by working primarily with digital design tools (a shift from Wendell Castle, who continued to make initial models by hand even as he started using CNC robots to carve). Stefan Bishop has developed a sculptural language that involves not just stacking boards like bricks but stacking them at angles in order to move his twisting tapeworm-like forms even further into dimensional space, achieving something of the energy of Carol Bove and Richard Deacon.

Casey McCafferty, ‘Byzantium Small’, 2020

COURTESY: Casey McCafferty / PHOTOGRAPH: Joseph Kramm

Then there is McCafferty, who has developed a soft, pillowy biomorphism that seems to be the contemporary foil to Castle’s late polished grandeur. He sketches loosely and freely in wood, playing massiness and imposing scale against an improvisatory, informal expressiveness, putting his abundantly evident craft skill at the disposal of his unorthodox imagination. McCafferty and his contemporaries are bringing stacked lamination back into the contemporary repertoire and renewing one of the most significant craft legacies of the American Studio movement.