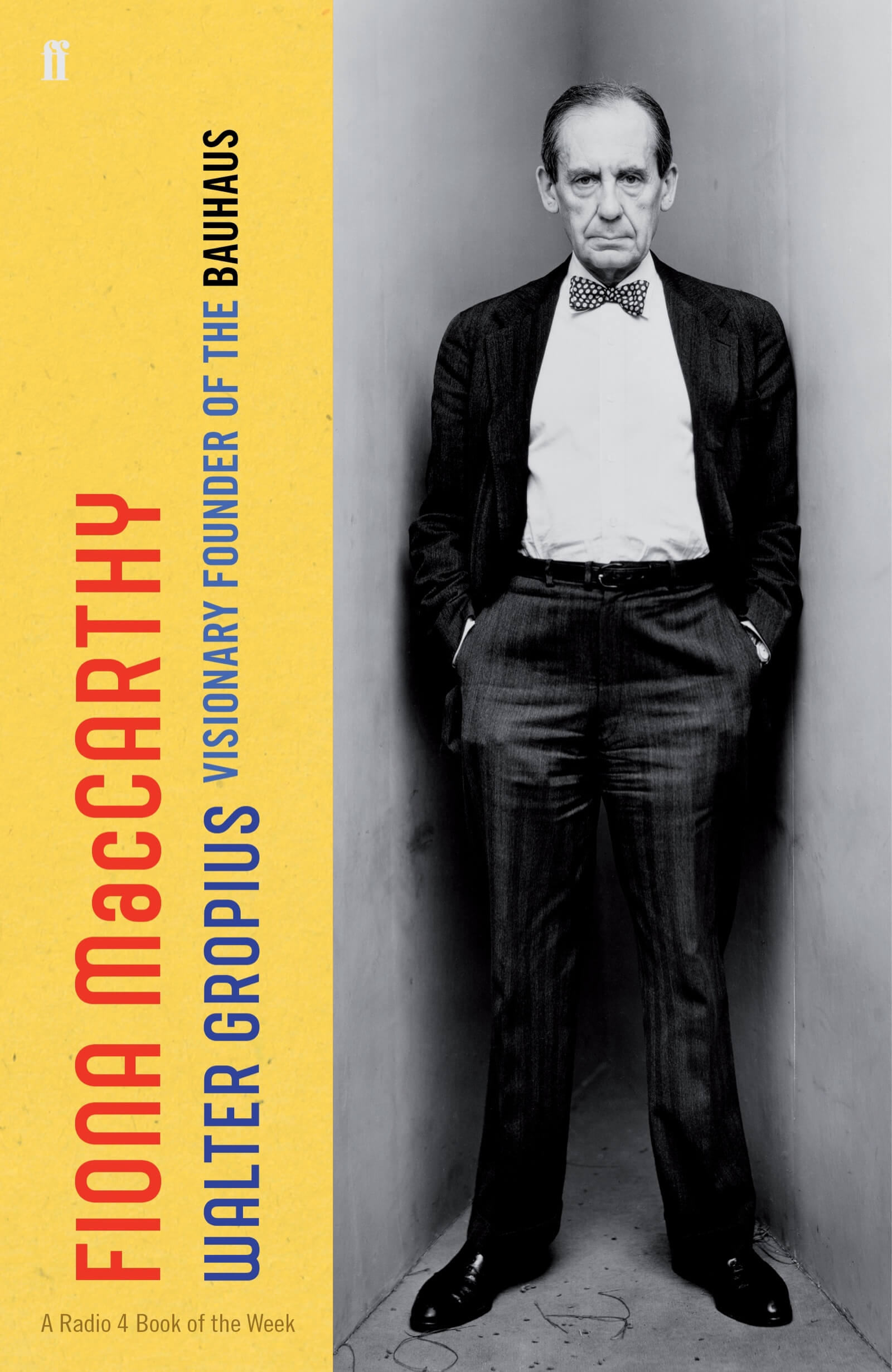

Walter Gropius: Visionary Founder of the Bauhaus

A biography of a pioneering master of modernist architecture.

Fiona MacCarthy

Faber & Faber, 2019

THE CENTENARY OF the Bauhaus has seen a fistful of books and exhibitions devoted to the German design school. But, arguably, the most high profile event has been the publication of Fiona MacCarthy’s book on Walter Gropius.

As subjects go, Gropius might not be an obvious choice for a biography that runs to nearly 500 pages. Over the years, after all, his reputation has taken a bit of a battering. As MacCarthy points out in an entertaining introduction this is largely down to a combination of Tom Wolfe’s (rather brilliant) satire From Bauhaus to Our House in which Gropius is, in MacCarthy’s words, “pilloried unjustly as the inventor of the monolithic high-rise buildings in our cities” – as well as the denigrating portrait of him painted in the memoir of his first wife Alma Mahler. The cover of the book does little to downplay this dowdy image: our hero stares seriously, if a little blankly, down the barrel of the camera lens, hair perfectly combed, poker dot bow tie in place. It hardly screams of a wild, passionate artist.

Walter Gropius

COURTESY: Faber & Faber

And yet, the man MacCarthy carefully uncovers lived quite an extraordinary life, that can be divided quite neatly into three parts: in Germany, Britain and the USA. A former design critic of The Guardian, MacCarthy is most famous for her book on Eric Gill, which lifted the lid on his string of abuses, including incest with his sisters and daughters as well as bestiality with the family dog. Gropius’s life was never this extreme but still contained plenty of colour. As he put it in a speech given in Chicago on his 70th birthday he had the “strong desire to include every vital component of life, instead of excluding them for the sake of too narrow and dogmatic an approach.”

BORN IN BERLIN in 1883 (only 12 years after German unification), there was a vein of architecture running through his family – his great-uncle Martin Gropius had formed one of the largest architectural firms in the city and his father had aspirations to build before settling into public service as a civic building official. His first commission for a farm building came from an uncle in 1905. Yet his life and career would never run smoothly – the two wars that tore through the twentieth century saw to that.

Gropius, it turns out, was a fine soldier, receiving an Iron Cross and the Bavarian Military Medal Fourth Class with Swords for his courage. He was once buried alive for three days. The experience must have taken its toll and, as the author points out, “The screaming jeebies that started in the First World War never really left him.” He would be plagued by insomnia for the rest of his days.

Fagus factory, Alfeld-an-der-Leine, 1913-15, designed by Walter Gropius and Adolf Meyer

COURTESY: Helen Mellor

In fact there is a significant streak of melancholy running through the book. His personal life was anything but straightforward. After starting a relationship with Alma Mahler, while she was still married to composer Gustav, the pair eventually married and had a daughter, Manon. But it was always fraught. Alma comes across as a prototype groupie, moving from talented artist to talented artist, leaving a path of destruction in her wake. The author lingers for sometime on her various sexual peccadilloes – one letter to Gropius talks of him placing his “sacred appendage” in her mouth. Predictably the marriage didn’t last and Gropius barely saw his daughter before her premature death in 1935. His much happier second marriage to Ise was still marred by her affair with Bauhaus tutor Herbert Bayer.

The Bauhaus building in Dessau, 1925-26, designed by Walter Gropius

COURTESY: Helen Mellor

Even the huge burst of creative energy that was the Bauhaus was constantly being interrupted by Germany’s post-Treaty of Versailles political and economic strife. That said, MacCarthy paints a vivid picture of those heady days, first in Weimar and then in Dessau, concentrating on the parties as much as the work. When things started to become increasingly difficult in Germany, Walter and Ise absconded to London for what turned out to be a frustrating sojourn before finally moving the US (and a position at Harvard) in 1937. The reader is left in little doubt that much of the rest of his career was spent attempting to, if not completely recreate, then at least recapture the essence of the Bauhaus. Wherever possible he liked to keep those early colleagues and friends around him – Marcel Breuer followed him to Harvard, for instance.

Was he a great architect? MacCarthy doesn’t really think so, at least not in the league of Mies – one of his successors at the Bauhaus – or Le Corbusier. She is at pains to point out he was never a very good draughtsman. However, she concludes that instead he was “a great architectural thinker with a vision of the meaning of art in modern life”. Which after reading this excellent, beautifully researched and written book, seems like a fitting tribute.