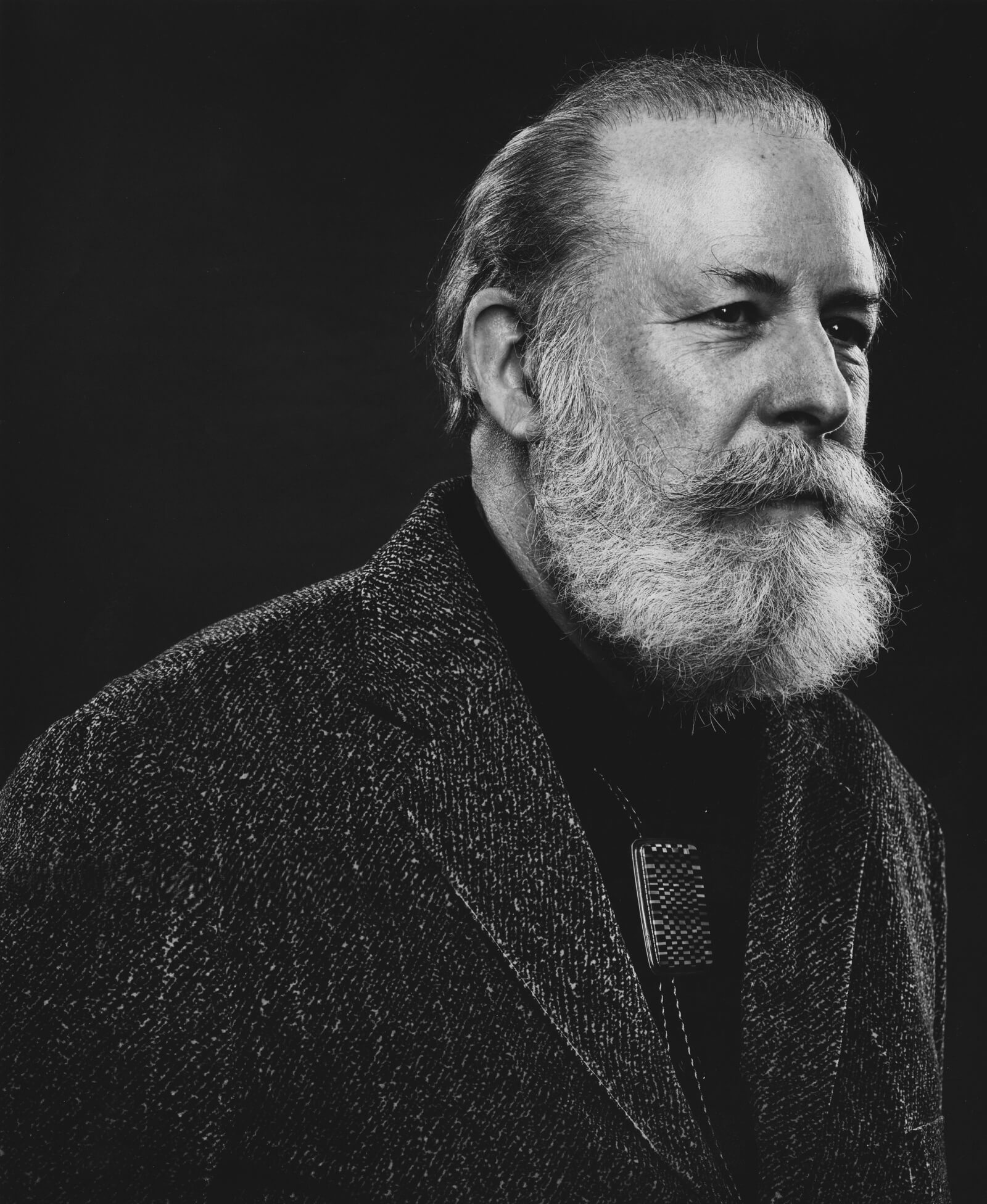

Barry Friedman / art dealer

Judith Gura meets ‘the man who rediscovered Art Deco’ and built a pioneering collection of contemporary design.

BARRY FRIEDMAN RETIRED five years ago, but you wouldn’t know it from speaking to him. He’s as active as when he was running one of the four New York galleries he opened over the previous five decades — except, perhaps, for more frequent sessions with a trainer at his local gym. “I don’t get around much anymore,” he says, then contradicts himself by mentioning upcoming travel to LA and Dallas-Fort Worth, citing recent sales, and acknowledging regular attendance at events abroad.

Barry Friedman

COURTESY: Erwin Olaf

His appearance nowadays at a gallery opening or design event draws a flurry of attention. Soft-spoken Friedman doesn’t ‘work the room’, but he’s easy to spot in a crowd. His white beard is one reason, another is his distinctive garb: sometimes Issey Miyake or vintage, but more often custom made suits or coats of striking fabrics found in his travels, with unusual hats (many made by his wife, fashion designer Patricia Pastor). Almost anyone in the collectible design field knows about him – he is the man who rediscovered Art Deco, who staged a museum-quality exhibition that designated him ‘The Chair Man’, and who owned or partnered in four groundbreaking galleries for art, design and photography.

Barry Friedman’s dining room: Art Deco table, chairs and sideboard by Leon Jallot; hanging fixture, style of Mallet-Stevens (above table); Venini glass turkey by Tony Zuccheri, vases by Michelozzi, black vase with red found object by Christiano Bianchin (on sideboard); Ingrid Donat cabinet (by window on right hand side)

COURTESY: Barry Friedman / PHOTOGRAPH: Timothy Doyon

A lifetime New Yorker, the 76-year-old Friedman has been a dealer since 1967, but began collecting when he was in elementary school (starting with four-leaf clovers) and has been buying and selling antiques since college. He worked his way through school, “I always had jobs, from the age of thirteen onwards,” he recalls, and majored in business at Pace University. An art history course in his last term was the first and last formal training in what turned out to be his chosen field. After graduation, he shopped for antiques at the weekends in New England while working as an accountant, a profession he left after finding he loved his hobby and hated his work. ”I collected $65 a week on unemployment,” he remembers, “It paid the bills.”

He went into business as a ‘runner’ with a borrowed $300, buying antiques (mostly glass) and reselling them to dealers. “I’ve always sold to dealers,” he says, “I still do.” He learned by careful observation, and voracious reading, finding sellers through ads in magazines like Antique Trader and Hobbies, and often ferreting out treasures that even seasoned professionals didn’t realise they had. He recalls buying a glass vase for $35 that he resold to a New York dealer for $350. Even so, finances were precarious; “I’d try to resell a piece before the check I wrote to pay for it cleared — or bounced.”

François-Emile Decorchemont, ‘Vase Hippocampe’, circa 1912-17. Sold at the three day auction, ‘Barry Friedman: The Eclectic Eye’, held at Christie’s New York, 25-27th March, 2014.

COURTESY: Christie’s

BY 1969, WHEN he rented space in an antiques centre on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, he’d become interested in then-forgotten ‘Style Moderne’ (soon known as ‘Art Deco’). He sold to “young people who couldn’t afford anything good,” though collectors like Barbra Streisand and Andy Warhol dropped by and became clients. In May 1970, he opened Primavera on Madison Avenue with his wife Audrey, and made his first buying trip abroad, to Paris, where they bought an Art Deco commode for the equivalent of $27. “It was my first piece of furniture,” he recalls. With such bargain prices, they spent $1,000 and shipped home a full container. Primavera became known for fine Art Nouveau and Art Deco objects, jewellery and furniture.

When the Friedmans divorced in 1973, Audrey kept the store and Barry continued his European trips, shifting focus to Symbolist and Pre-Raphaelite paintings and posters, and selling from his apartment. “I was good at finding things,” he says, to explain his growing success despite changing categories. After moving to a capacious Madison Avenue apartment in 1975, he broke through to an adjacent commercial space to create Barry Friedman Ltd. He went on to host exhibitions in this space including the celebrated chair show in 1984, which paired iconic pieces by Ruhlmann, Prouvé, Mackintosh, Hoffman and Summers with related artworks. He also staged exhibitions on Bauhaus design, Wiener Werkstätte and Rietveld furniture. Counter to the usual dealer practice of consigning, Friedman purchased the objects for most of his shows, and often produced catalogues as well. Recognised for his impeccable taste and ability to anticipate market trends, Friedman developed a clientele of dealers and museums as well as a network of collectors, educating all of them as he marketed old and forgotten, or current and undervalued artists and designers like Christopher Dresser, Tamara de Lempicka, Yoichi Ohira, and Ron Arad.

Ron Arad, ‘Oh Void 1’ chair, 2004. Sold at the three day auction, ‘Barry Friedman: The Eclectic Eye’, held at Christie’s New York, 25-27th March, 2014.

COURTESY: Christie’s

He recalls early bargains including his first Josef Hoffmann piece (a small silver box bought for $25 at a 1970 Paris flea market, which would bring thousands today), and a de Lempicka painting for about $5,000 (good ones now sell for millions). Furthermore, Ohira vases like one he first sold for $1,900 now bring as much as $250,000. Friedman’s increasingly varied interests led to joint ventures: a photography gallery with Edwin Hauck from 1991 to 1995, and a gallery for Art Deco with Paris-based friends Cheska and Robert Vallois from 1999 to 2004, by which time his gallery occupied two floors in an East Side townhouse shared with antiques dealer Didier Aaron.

BARRY FRIEDMAN LTD was the first 20th century dealer — and for two years the only one — to be invited into the prestigious Winter Antiques Show, where he exhibited for almost 20 years. He also showed at PAD in Paris and London, Art Basel, Modernism and Salon, though agrees with most dealers that nowadays there are too many such events. “You get faired out,” he comments.

Barry Friedman’s foyer: Massimo Micheluzzi, glass chandelier; Ingrid Donat, console; Nendo, ‘Cabbage Chair’, 2008; Angélique, life-size motorcyclist figure in glass case

COURTESY: Barry Friedman / PHOTOGRAPH: Timothy Doyon

As he moved into contemporary design, Friedman began to buy and sell Italian glass with Marc Benda; “We liked each other’s taste,” he explains. Benda joined the business in 2002, and in 2007 the partnership of Friedman Benda opened in Chelsea, in an airy modern space that could accommodate the large works of art furniture in which the gallery has specialised, introducing designers like Nendo, Joris Laarman and Paul Cocksedge, reintroducing Ron Arad and Ettore Sottsass, and repositioning Wendell Castle. When Friedman retired, Benda chose to keep the name. ”We still do stuff together. If I find something, I call Marc and we might buy it together … and when I want to sell something, I usually sell it through Marc.”

Friedman’s retirement in 2014 sent shock-waves through the industry — who else could be counted on to foresee the next big trend? Christie’s staged a three-day sale of objects from his own collection, though, as a visitor realises, there’s still plenty left.

Ingrid Donat, ‘Commode aux 14 Tiroirs’, 2002. Sold at the three day auction, ‘Barry Friedman: The Eclectic Eye’, held at Christie’s New York, 25-27th March, 2014.

COURTESY: Christie’s

Friedman and Patricia Pastor, whom he married in 1983, live in a spacious apartment in the Flatiron district, around the corner from the by-appointment-only gallery he maintains. The living room is an eclectic commingling of styles that includes a six-foot-long etched bronze coffee table by Ingrid Donat, an Art Deco buffet by Leon Jallot, a monumental Tord Boontje fig-leaf wardrobe, and a chair of steel pipes by Piet Hein Eek, all sharing space with comfortable sofas and a medley of glass and ceramic objects, sculpture, paintings and graphics.

Barry Friedman in his living room sitting on Piet Hein Eek’s ‘Tube Chair’; Tord Boontje, monumental ‘Fig Leaf’ wardrobe’ (left hand wall), 2008; Josef Hoffmann, brass vases, and Yoichi Ohira, agate vases (on mantlepiece); Ingrid Donat’s bronze armchairs and table (facing fireplace)

COURTESY: Barry Friedman / PHOTOGRAPH: Timothy Doyon

Though his professional dealings have followed a trajectory from one style to another, according to his feel for the market, Friedman’s personal taste has been relatively constant. He’s always loved glass, never entirely abandoned Art Deco, and names Belgian Symbolist Ferdinand Khnopff as his favourite painter. But he’s stayed open to new discoveries. “For the past few years my biggest passion has been South East Asian antiquities — though I have to keep selling things to pay for the collection,” he admits. But what he describes as his “secret passion” endures; hung along three walls of a large storage room are some 6,000 vintage men’s ties — painted and printed, political and provocative, a cornucopia of colours and styles from the 1880s to the 1950s acquired over several decades. “I don’t even remember when I bought the first one,” Friedman reflects. He obviously takes as much pleasure in them as in his six-figure finds.

Asked about the book he’s reportedly writing about the treasures he’s bought and sold over the years, he replies, “I’m on a little sabbatical, but I’ll get back to it.” Whatever he’s doing, it’s safe to assume that when the next new thing comes along, Barry Friedman is likely to spot it first.

Nendo, ‘Cabbage Chair’, 2008. Sold at the three day auction, ‘Barry Friedman: The Eclectic Eye’, held at Christie’s New York, 25-27th March, 2014.

COURTESY: Christie’s