Collectible design and the circular economy

Upcycling, recycling, and using unusual natural products – designers are pushing boundaries in their quest for sustainability.

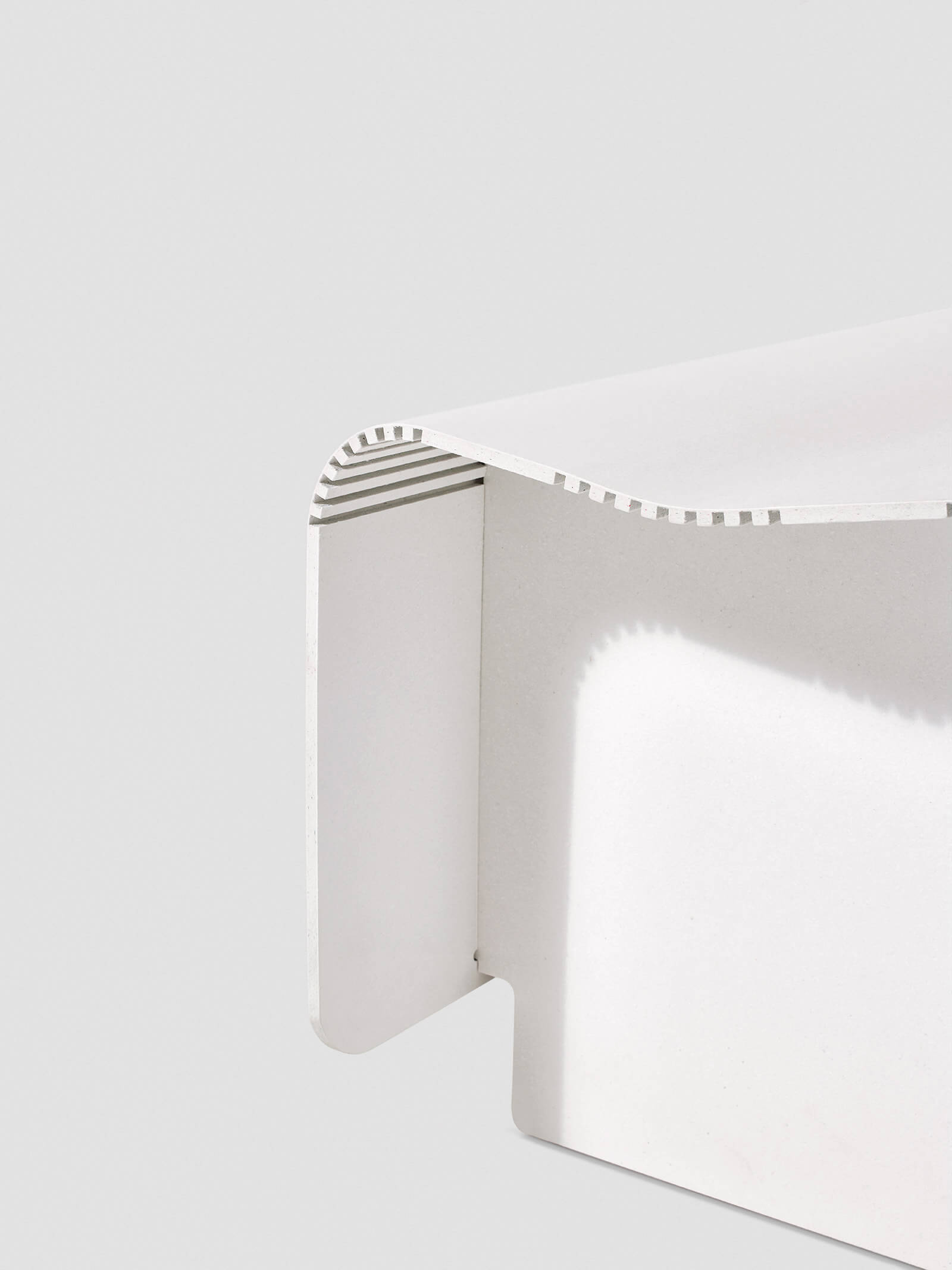

Installation view, Karl Lagerfeld ‘Architectures’ exhibition

COURTESY: Carpenters Workshop Gallery

KARL LAGERFELD’S ‘ARCHITECTURES’ collection of sculptural works includes exquisite tables, fountains and mirrors made of Arabescato Fantastico or Nero Marquina marble. The items are typical of the collectible end of the design market: beautifully-crafted limited editions, or one-offs, created from precious or semi-precious materials and selling for thousands of pounds.

Is it possible to reconcile collectible design like this with current concerns about the planet’s health and sustainability? Not at first glance, but beneath its polished obsidian surface, this sector proves to have some unexpected eco-qualities. Couple these with some designers’ efforts to push the boundaries of what it means to be a highly-valued object, and collectible design starts to have something responsible to talk about.

Violaine Buet, woven piece made from seaweed

COURTESY: Violaine Buet / PHOTOGRAPH: Laurent Desmaret

For some time, designers of mid- and to an extent low-priced products have been using sustainability as a virtue. IKEA’s kitchen system KUNGSBACKA is covered in a plastic foil made of recycled PET (polyethylene terephthalate) bottles. Created by Swedish design firm Form Us With Love, a whole KUNGSBACKA kitchen uses 1,000 such bottles. The Swedish retailer can exploit this as a good news story.

Mass volume designers are taking their cues from their customers. “The mass consumer consciousness has changed a lot in the last few years,” says Clare Brass, founder and director of Department 22, which offers consultancy and training for innovation and sustainable design development. Many middle- and lower- income consumers now vote with their feet. NYU Stern’s Center for Sustainable Business says that 50% of the sales growth in consumer packaged goods (CPG) in the US between 2013 and 2018 came from sustainability-marketed products. According to the research, in more than 90% of the CPG categories, sustainability-marketed products grew faster than their conventional counterparts.

Max Lamb benches (made from Solid Textile Board, using end-of-life cotton and wool textiles), Really exhibition, Salone del Mobile, 2017

COURTESY: Really / PHOTOGRAPH: Angela Moore

At the top end of the design world, any efforts towards sustainability are being driven by the designers themselves. By experimenting with unexpected materials, they are helping their audiences reconsider what they think of as valuable. Meanwhile, the mechanics of collectible design production are also gentler on the planet. Proximity of production, size of batches and price-point alongside those unorthodox materials can all contribute towards a sculptural object’s sustainability. This means that if they’re so minded, collectors, galleries and museums can make ecologically responsible purchases.

Max Lamb bench (made from Solid Textile Board, using end-of-life cotton and wool textiles), Really exhibition, Salone del Mobile, 2017 (detail)

COURTESY: Really / PHOTOGRAPH: Angela Moore

Brass points out that as far as the planet is concerned, producing anything is worse than producing nothing, because any product is inherently unsustainable. This so irked Brass that she gave up her career as a product designer, as “I couldn’t live with myself.” In which case, producing less is better than producing more. Designers of limited edition collectible objects fit the bill, as are those making one-offs, and bespoke, commissioned pieces.

Gloria Cortina, ‘North & South’ cabinet, 2018-19 (bespoke piece)

COURTESY: Gloria Cortina

In contrast, Brass explains that “the sustainability targets of big volume companies are lower than their growth targets, because their volumes will be higher, they can never catch up.” And if a beautiful big-ticket item is also well-made, then it will last and can be passed on – limited edition or bespoke pieces should never end up in landfill.

Alex Hull, ‘Line’ chair, 2018 (bespoke piece)

COURTESY: Alex Hull Studio / PHOTOGRAPH: Mark Reeves

“The idea that you need a new dining table every five years is mad,” says Jane Withers, whose exhibition Really, at Salone del Mobile 2017, explored design’s role in the circular economy. The show featured products made from up-cycled textiles, highlighting the opportunities for designers who embrace the idea that end-of-life could become the start of a new life.

Max Lamb bench made from Solid Textile Board (using end-of-life cotton and wool textiles)

COURTESY: Really / PHOTOGRAPH: Angela Moore

“Really, at Salone del Mobile 2017, featured products made from upcycled textiles”

Max Lamb bench made from Solid Textile Board (using end-of-life cotton and wool textiles) (detail)

COURTESY: Really / PHOTOGRAPH: Angela Moore

“It highlighted the opportunities for designers who embrace the idea that end-of-life could become the start of a new life.”

HISTORICALLY, TOP-QUALITY furniture was always made of top-quality materials, typically extracted from quarries, mines or forests. But that’s no longer a given. A handful of designers are imbuing rubbish with value. Brodie Neill and Stuart Haygarth are known for their clever use of waste, and Fernando and Humberto Campana also have such collections to their name.

Haygarth’s ‘Tide Chandelier’ is created from plastic debris he finds when walking his dog on Dungeness beach. But to elevate such a design into the realms of the collectible is a challenge. “There’s a very slim line between a mess of rubbish and an archive of plastic,” he says, “it’s a lot to do with the skill of putting things together, and the visual nature of the object.” While the ingredients may be free, hours of labour go into making each item. “Each piece (of debris) is meticulously cleaned,” he says, “and then there’s a massive editing process.”

Stuart Haygarth, ‘Tide’ chandelier, 2004

COURTESY: Stuart Haygarth

Likewise, the Campana brothers’ 2017 Hybridism show at Friedman Benda in New York was “focused on things that we collect on the streets … I picked up discarded toys and other objects” reported Humberto at the opening, “and then I cast them (in bronze). We are making rubbish into art.”

Campana Brothers, ‘Noah Wall Shelf’, 2017

COURTESY: Carpenters Workshop Gallery

Campana Brothers, ‘Noah Wall Shelf’, 2017 (detail)

COURTESY: Carpenters Workshop Gallery

Along with upcycling (rather than its poor relation recycling) these pieces tick two more sustainability boxes: they are likely to be made of materials sourced close to the designers’ workshops, which in turn reduces transportation miles. In contrast, “mass-market products are usually produced on the other side of the world,” says Brass.

Despite these upsides, it’s a hurdle getting upcycling accepted. Designers who’ve been operating at this end of the market for some time recognise there’s been an image problem for some of their audience. “It’s all to do with shifting people’s perception of what waste is,” says Neill, who created the Flotsam series with ocean plastic, and who admits that for private collectors “it’s a big ask.”

Brodie O’Neill, ‘Flotsam Black’, 2017 (made from Ocean Terrazzo composite)

COURTESY: Brodie O’Neill

In contrast, institutions such as museums and public collections have been receptive, because of the educational role of such pieces, “and because of that, private collectors are now coming through,” says Neill. He is now getting commissions for site-specific pieces.

Like IKEA’s kitchen designers, those designers of environmentally-aware collectibles also have an engaging story to tell – and with a good story comes raised awareness. Neill’s Flotsam series is made of Ocean Terrazzo, a composite comprising fragments of plastic washed up on shorelines worldwide. He developed it with scientists, researchers, environmental experts, beachcombers, engineers, artisans and manufacturers. “These people are touched by it,” says Neill of private collectors, “because their other common interest is probably sailing.”

Brodie O’Neill, ‘Gyro’ table, 2016 (made from Ocean Terrazzo composite)

COURTESY: Brodie O’Neill

Such forays into extreme innovation and upcycling are laudable, but “they don’t make the blindest bit of difference to the big picture,” laments Brass. That’s if they stay niche. However, materials experimentation has potential value beyond this immediate market. “A lot of designers use the high-end gallery and collectible side (of the sector) to experiment … in a way that industry can’t afford to,” says Withers.

Violaine Buet, range of seaweed samples

COURTESY: Violaine Buet / PHOTOGRAPH: Pierre-Yves Dinasquet

One such designer is Julia Lohmann, who experiments with maggots and sheep stomachs, and who has pieces in major public and private collections worldwide. As designer-in-residence at the V&A in 2013, she set up the Department of Seaweed, which explored the marine plant’s potential as a design material.

Julia Lohmann, Department of Seaweed, ‘Kelp Mask and Wings’, 2013

COURTESY: Julia Lohmann, Department of Seaweed / PHOTOGRAPH: Petr Krejc

In the last decade, some of the interesting ideas and materials that have emerged through galleries “have gone on to inform other things”, says Withers. She cites Adidas’s manufacture of shoes out of fishing nets, which has “only happened because there’s been so much material research”.

In this vein, Neill is trying to make his Ocean Terrazzo more cost-effective, so that it could be used on a larger scale for flooring and cladding in construction. “There’s plenty of plastic out there, but it’s about scaling it up,” he says.

In the meantime, such designers are in a position to set a good example. And perhaps as a new generation of collectors comes of age, their tastes will be more environmentally responsible, which will help secure sustainability’s place in this field.

Julia Lohmann introduces the Department of Seaweed

COURTESY: Julia Lohmann, Department of Seaweed