Accidents Will Happen / Creative Salvage, 1981-1991

Early, punk-inspired work from a group of London-based designers who went on to become contemporary stars.

13th January – 12th February 2022

Friedman Benda, New York

Ron Arad, ‘Bookcases’, 1983

COURTESY: Ron Arad & Friedman Benda

IN SEPTEMBER, 1984, three dynamic Young Turks showcased their idiosyncratic furniture assembled from scrap materials such as scaffolding clamps, slabs of granite and fragments of glass in an exhibition in a closed-down hairdresser on Kensington Church Street, West London. Calling themselves Creative Salvage, Tom Dixon, Mark Brazier-Jones and Nick Jones created rough-and-ready chairs and tables in the hair salon’s windows in full view of passers-by in the run-up to the show. This attention-grabbing spectacle helped to publicise the exhibition, which they followed up by another in the same premises in 1985.

Tom Dixon, ‘Regal Chair’, circa 1985

COURTESY: Tom Dixon & Friedman Benda

Now gallery Friedman Benda in New York is spotlighting pieces created by the Creative Salvage crew as well as by André Dubreuil (who joined forces with this trio later), Ron Arad, Danny Lane, Jon Mills and Deborah Thomas in a show entitled ‘Accidents Will Happen: Creative Salvage, 1981-1991’.

André Dubreuil, ‘Paris Chair’, circa 1988

COURTESY: André Dubreuil & Friedman Benda

Brazier-Jones, Dixon and Jones penned an informal, anti-consumerist manifesto printed on the invite to the 1985 exhibition. “Creative Salvage is a rapidly expanding development company. We are convinced that the way ahead does not lie in expensive, anonymous, mass-produced, high-tech products. But in a more decorative and human approach to industrial design,” it read forcefully, poor punctuation notwithstanding. “The key to Creative Salvage’s success does not lie in the expensive research and development costs of modern day products. But in the recycling of scrap to form stylish and functional artefacts for home and office.”

Mark Brazier-Jones, ‘Robot Table’, 1989-90

COURTESY: Mark Brazier-Jones & Friedman Benda

The work certainly stood out for being different when you consider that the design world was much more circumscribed at the time – the key styles being either the chintzy Laura Ashley look, or hard-edged, industrial high-tech.

Creative Salvage’s work embodied punk values, including an indifference to classical virtuosity: these designer-makers were self-taught and assembled their furniture in a way that mirrored punk’s democratic, DIY belief that anyone could pick up a guitar and play music. As with punk fashion, Creative Salvage found beauty in discarded materials that many would have deemed junk.

Ron Arad, ‘Horns Armchair’, 1985

COURTESY: Ron Arad & Friedman Benda

Conferring more outsider status still on these rebels was the fact that many of them weren’t British-born, says Williams: “Dixon was born in Tunisia, Danny Lane is American – but they all gravitated to London.” Certainly, West London’s alternative culture and music were interwined with their furniture. Dixon played bass guitar in a funk band called Funkapolitan, which once supported The Clash. “One night, the band that Funkapolitan were supposed to perform with failed to turn up, so Tom spontaneously made furniture on stage,” says Williams. Creative Salvage also put on warehouse parties in London.

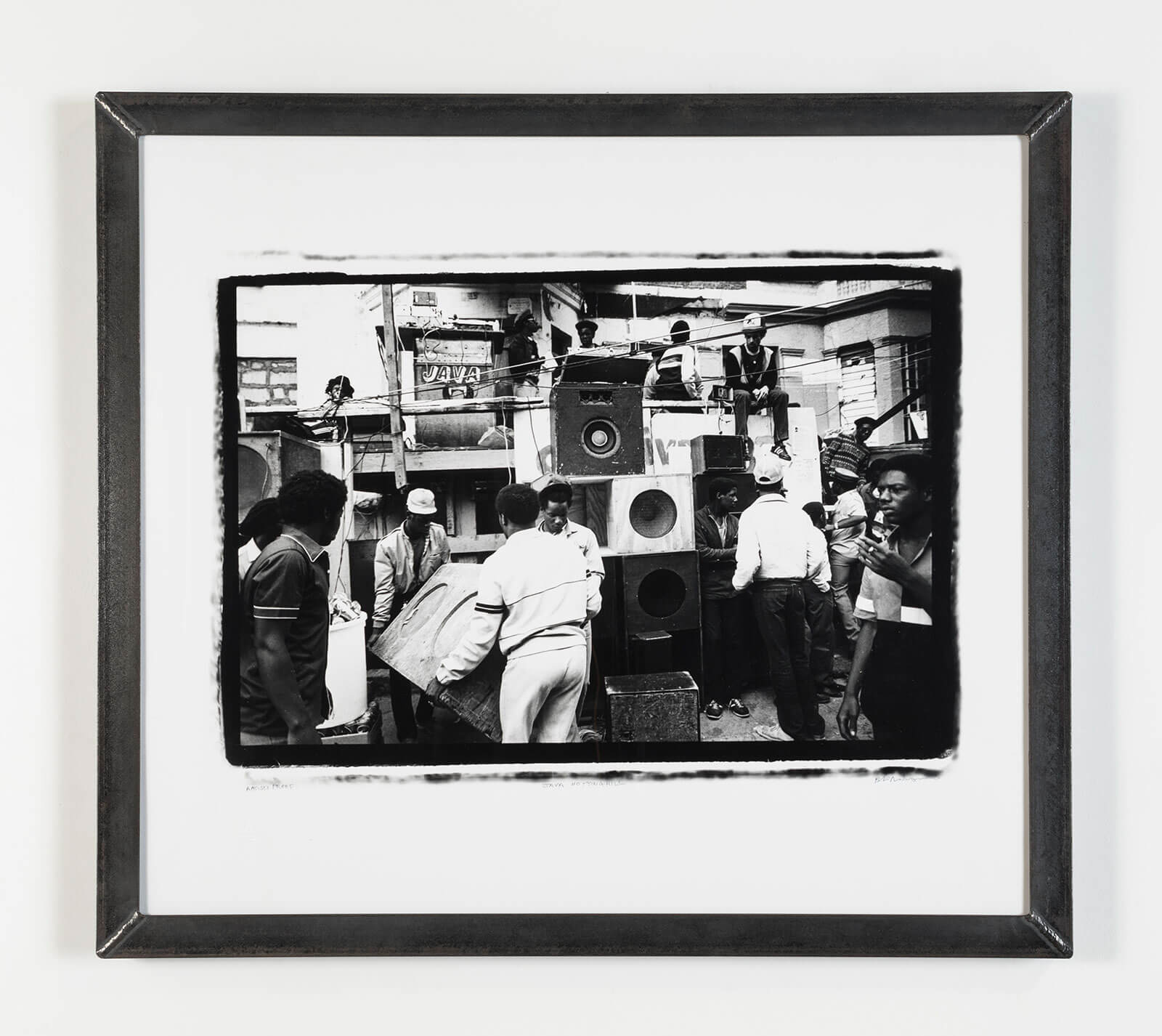

The exhibition includes evocative ephemera of the time, which helps to contextualise the furniture, including early 1980s club flyers and photos by Peter Anderson of piled-up sound systems and dancing crowds at the Notting Hill Carnival.

Peter Anderson, ‘Java Sounds System’, Nottinghill Carnival, 1983

COURTESY: Peter Anderson & Friedman Benda

“One reason for putting on this show is that this was a very exciting period of British design,” says curator Gareth Williams, an art advisor and co-author with Nick Wright of Cut and Shut: The History of Creative Salvage, which documents this relatively unknown slice of design history. “Aside from this, this work is relevant now because these designers recycled materials, rescued them from landfill.”

Jon Mills, ‘Dog Bollock Wardrobe’, 1988

COURTESY: Jon Mills & Friedman Benda

“They assembled their furniture in a way that mirrored punk’s democratic, DIY belief that anyone could pick up a guitar and play music”

Jon Mills, ‘Dog Bollock Wardrobe’, 1988 (detail)

COURTESY: Jon Mills & Friedman Benda

“As with punk fashion, these designer-makers found beauty in discarded materials that many would have deemed junk”

“Dixon, Brazier-Jones and Dubrueil went on to become international names in the design world, but their later work has overshadowed their early output,” Williams explains. This may be partly because in the early 1980s, Creative Salvage and their like-minded peers weren’t careerist but were caught up in the intensely political, alternative post-punk era, valuing artistic self-expression and spontaneity over commercial success and slick end products.

Mark Brazier-Jones, ‘Dressing Table’, 1988

COURTESY: Mark Brazier-Jones & Friedman Benda

The words “Accidents Will Happen” in the show’s title made me think of the opening track of Elvis Costello’s 1979 album ‘Armed Forces’. But Williams explains it’s a quote from Joe Rush, who co-founded the performance art group Mutoid Waste Company. “His work wasn’t planned and he used found materials,” he says.

Ron Arad, ‘Rollying Volume prototype’, 1989

COURTESY: Ron Arad & Friedman Benda

Dixon took a similarly extempore approach when building his structures using a welding torch. He has compared welding to a “magical experience” and described it in alchemical terms as an ability to “turn scrap metal into gold”. The show includes several of his chairs, tables, candlesticks and a mirror.

Tom Dixon, ‘Pylon Mirror’, 1989

COURTESY: Tom Dixon & Friedman Benda

Arad, meanwhile, had already begun experimenting with found materials, taking a more entrepreneurial approach. In 1981, with Caroline Thorman he co-founded his design studio and showroom One Off in newly trendy Covent Garden, which sold his iconic ‘Rover Chair’. Inspired by Picasso and Duchamp’s ready-made sculptures, this fused a leather-covered Rover car seat picked up in a scrapyard with tubular steel and Kee Klamp joints. Friends of the Earth featured it on the cover of its magazine.

The Friedman Benda show displays Arad’s ‘Concrete Stereo’ pieces – Hi-Fi embedded in what looks like excavated concrete – which brings to mind strange archaeological finds unearthed several centuries in the future. They are perfect examples of the early 1980s “post-apocalyptic” style that encompassed the movie Mad Max and the shockingly frayed black and grey clothes of a new wave of Japanese designers, notably Rei Kawakubo.

Ron Arad, ‘Concrete Stereo’, 1983

COURTESY: Ron Arad & Friedman Benda

Williams comments, “The connection between Creative Salvage and the other designer-makers was quite informal – apart from their aesthetics, hands-on working methods, use of found materials and the fact that they were all in London. It was mainly based around exhibitions.” In 1985, for instance, One Off held a solo show of Dixon, who also took part in several group shows there, too. Lane and Mills worked with Arad and exhibited at Liliane Fawcett’s Notting Hill gallery Themes and Variations, which opened in 1984 and also showed work by Dixon, Brazier-Jones and Dubrueil.

One interesting aspect of the designer-makers in this show was their tendency to forge an individual visual language, partly fostered by their love of self-expression. Dubreuil’s furniture is decorative, its filigree-like frames forming fanciful arabesques.

André Dubreuil, ‘Early Ram Chair’, 1986

COURTESY: André Dubreuil & Friedman Benda

Brazier-Jones’s style was similarly romantic, evidenced by a chandelier for legendary King’s Road shop Rococo Chocolates (which opened in 1983). Also on display are Thomas’s comparatively ethereal wall lights fashioned from glass shards.

Deborah Thomas, ‘Pair of Wall Lights’, circa 1991

COURTESY: Deborah Thomas & Friedman Benda

Yet Danny Lane’s throne-like ‘Solomon Chair’ made of steel and stacked glass, and his ‘Etruscan Chair’ with its ragged yet polished edges, have the same appealingly crude quality as Dixon and Arad’s work. And Mills’s work, such as his ‘Dan Dare Chair’ of circa 1987, which combines hammered and welded steel and a radar dish, is surprisingly pop.

Danny Lane, ‘Etruscan Chair’, 1988

COURTESY: Danny Lane & Friedman Benda

Perhaps these designer-makers’ early work has been largely overlooked because they didn’t create work with longevity in mind. “When they were starting off, they weren’t thinking about things in the long run,” says Williams. “They weren’t taking things too seriously – their approach was playful.”

Tom Dixon, ‘Space Age Chair’, 1987-1988

COURTESY: Tom Dixon & Friedman Benda

Yet now the resulting one-off pieces are commanding attention, their charm partly springing from their makers’ love of free-wheeling creativity and youthful disregard for conventional success.

Accidents Will Happen: Creative Salvage, 1981-1991 at Friedman Benda.