Carlo Mollino / Hyperformal Allusions

A historic set of Mollino furniture, on public view for the first time, enriches the Triennale Milano collection.

Triennale Milano

4th September – 7th November 2021

Installation view

COURTESY: © Triennale Milano / PHOTOGRAPH: Gianluca Di Loia

THE TWENTIETH-CENTURY polymath Carlo Mollino was an important figure in Turin’s cultural scene. A trained architect, he also became famous for creating sinuously-curved wooden furniture and for making erotic Polaroids of scantily-clad women. But until recently, Triennale Milano – Milan’s design museum – only had one piece of his furniture in its collection.

This makes the recent acquisition of the living room that Mollino (1905-1973) designed in the mid 1940s for Casa Albonico, a family house in Turin, particularly remarkable. A striking configuration of the living room is now being unveiled to the public for the first time at the Triennale. It comprises a three-piece suite, table, cabinet, cupboard, set of chairs and preparatory drawings conveying Mollino’s multifaceted interests.

Installation view

COURTESY: © Triennale Milano / PHOTOGRAPH: Gianluca Di Loia

The fact that this ensemble belongs to the Triennale is a significant achievement. Last summer, Milan’s export office received a request on behalf of the Albonico family to take the furniture abroad, so it could be exhibited at a European design museum. The Triennale refuses to divulge the museum’s name, only that the furniture was “already leaving for Germany” when the Ministry of Culture and the Triennale intervened to ensure that the furniture would not leave the country permanently.

The dossier for the export request included an error, claiming that the pieces dated from 1954-1956. Had they been under 70 years old, they would have been subject to a simplified export procedure. Noticing the error, the export office investigated and discovered that they were a decade older. The Triennale and Manolo De Giorgi, an expert on Mollino, subsequently declared them to be of cultural interest and the export permit was denied. This led to the Ministry of Culture purchasing the pieces from the Albonico family last November.

Installation view

COURTESY: © Triennale Milano / PHOTOGRAPH: Gianluca Di Loia

“It was a tremendous experience and very lucky for the institution,” says Marco Sammicheli, the Triennale’s curator of design, fashion and crafts. “Thanks to this alliance between the Ministry of Culture and the Triennale, we’re able to present to the audience a collection of Mollino’s original pieces that no one has seen before, either in Italy or abroad.”

Carlo Mollino, ‘Table’, circa mid-1940s

COURTESY: © Triennale Milano / PHOTOGRAPH: Gianluca Di Loia

The acquisition has arisen at a time when prices for Italian furniture are skyrocketing at auctions internationally and the country is on a mission to preserve its heritage. Last October, a dining table from 1950 by Mollino sold for a staggering $6.2m at Sotheby’s. It had been consigned by the Brooklyn Museum, which needed to raise funds during the pandemic. The sale was a cruel blow to the Italian state that had donated the table to the museum in 1954.

As the Casa Albonico pieces date from the 1940s, the acquisition enables the Triennale – whose collection previously started with the 1950s – to become historically richer. “We now have a gem of design from before 1946, so these pieces are really a milestone for the Triennale’s collection,” Sammicheli says.

Carlo Mollino, ‘Chair’, circa mid-1940s

COURTESY: © Triennale Milano / PHOTOGRAPH: Gianluca Di Loia

Mollino designed the Casa Albonico furniture in his late thirties for the home of his friend, the engineer Paolo Albonico, and had it made by the crafts firm, Apelli, Varesio & Co. As the Albonico family used the furniture for decades, it all needs to be carefully restored – a process that the Triennale will continue after the exhibition. The sofa and armchairs, whose fabric was changed several times due to wear and tear, will be reupholstered in the original pink silk fabric with floral motifs.

“We have in our hands all the elements [concerning] the genesis of these specific pieces,” Sammicheli enthuses about the considerable research involved. Following the restoration, the group of furniture will be incorporated into the display of the Triennale’s permanent collection in 2023.

What’s intriguing is how the pieces are revealing of Mollino’s passions and collaborations. The wooden cabinet features a small bronze sculpture of a kneeling nude in between the top and drawers by Mollino’s friend, the artist Umberto Mastroianni. Mastroianni, for whom Mollino had designed a studio-house, was loosely inspired by Boccioni’s dynamic Futurist masterpiece, ‘Unique Forms of Continuity in Space’ (1913). The cabinet’s interplay of horizontal and vertical planes and contrasting woods further exemplifies Mollino’s interest in volumes and shapes.

Carlo Mollino, ‘Cabinet’, circa mid-1940s

COURTESY: © Triennale Milano / PHOTOGRAPH: Gianluca Di Loia

The figurative form is integrated in a different way in the backrests of the set of chairs. “In the backrests, you can really see the back of a human being; the structure relates to human bones and one of the joints is like a vertebra,” Sammicheli says.

The array of detailed drawings, meanwhile, demonstrates a precision linked to engineering, aviation and physics. Indeed, Mollino, the son of a civil engineer, was also an aerobatic pilot and ski instructor with an aptitude for techniques as well as aesthetics.

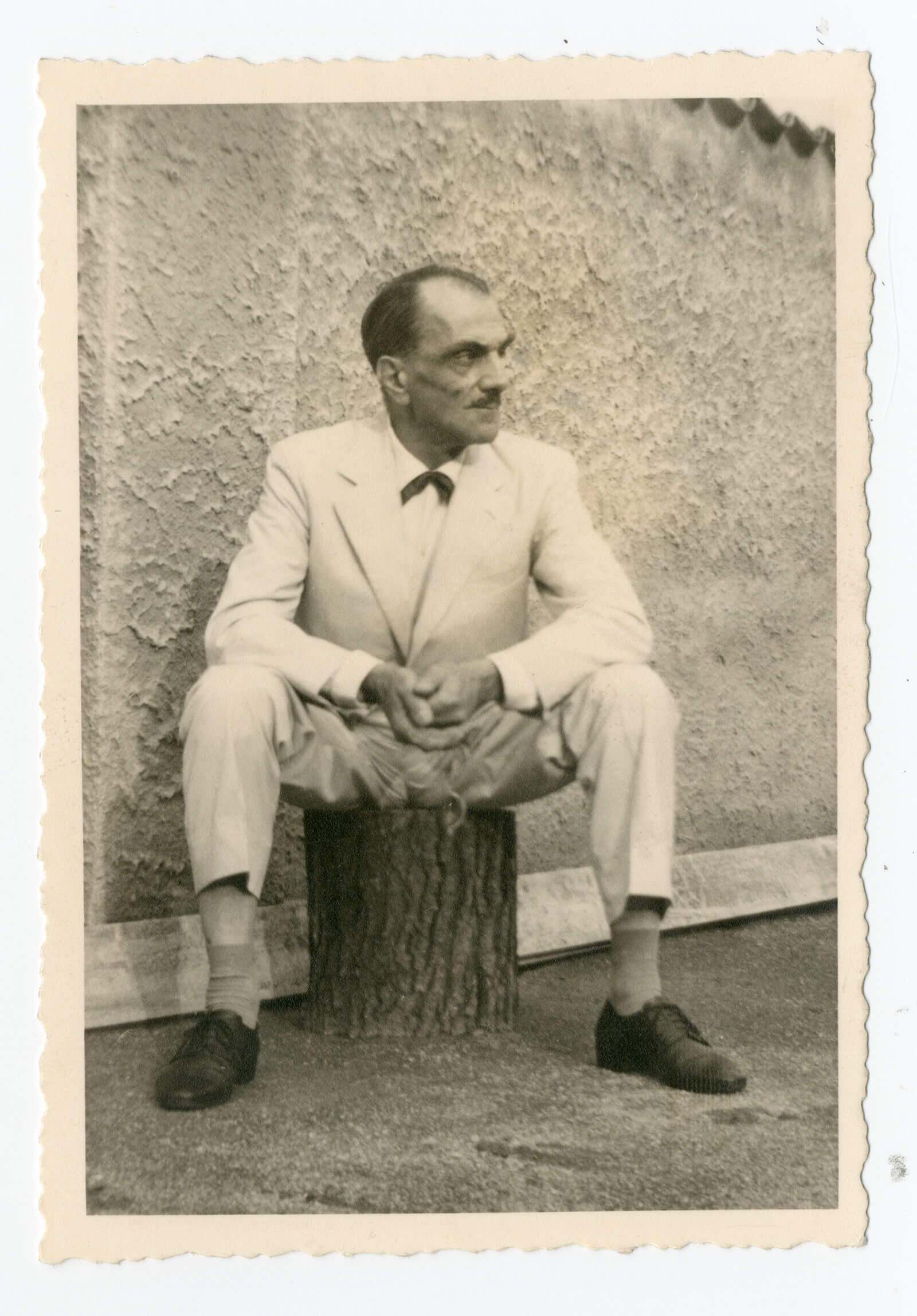

Carlo Mollino

COURTESY: Turin Polytechnic, Gabetti Library Archives Section, Carlo Mollino Fund

Crucially, the acquisition aims to illuminate a more serious side to Mollino’s legacy. “We built up a network of experts between Milan and Turin in order to deliver this scientific approach to his work and somehow erase this nocturnal mythology around Mollino,” Sammicheli says. “Of course, we knew about his passion for erotic photography but ultimately he was an incredible architect and very talented engineer.”

Carlo Mollino: Hyperformal Allusions at Triennale Milano.