Comfort

Is comfort a sedative? Is discomfort intellectually superior? An exhibition that provides a philosophical foray into the relationship between design and comfort.

Friedman Benda, New York

9th January – 15th February 2020

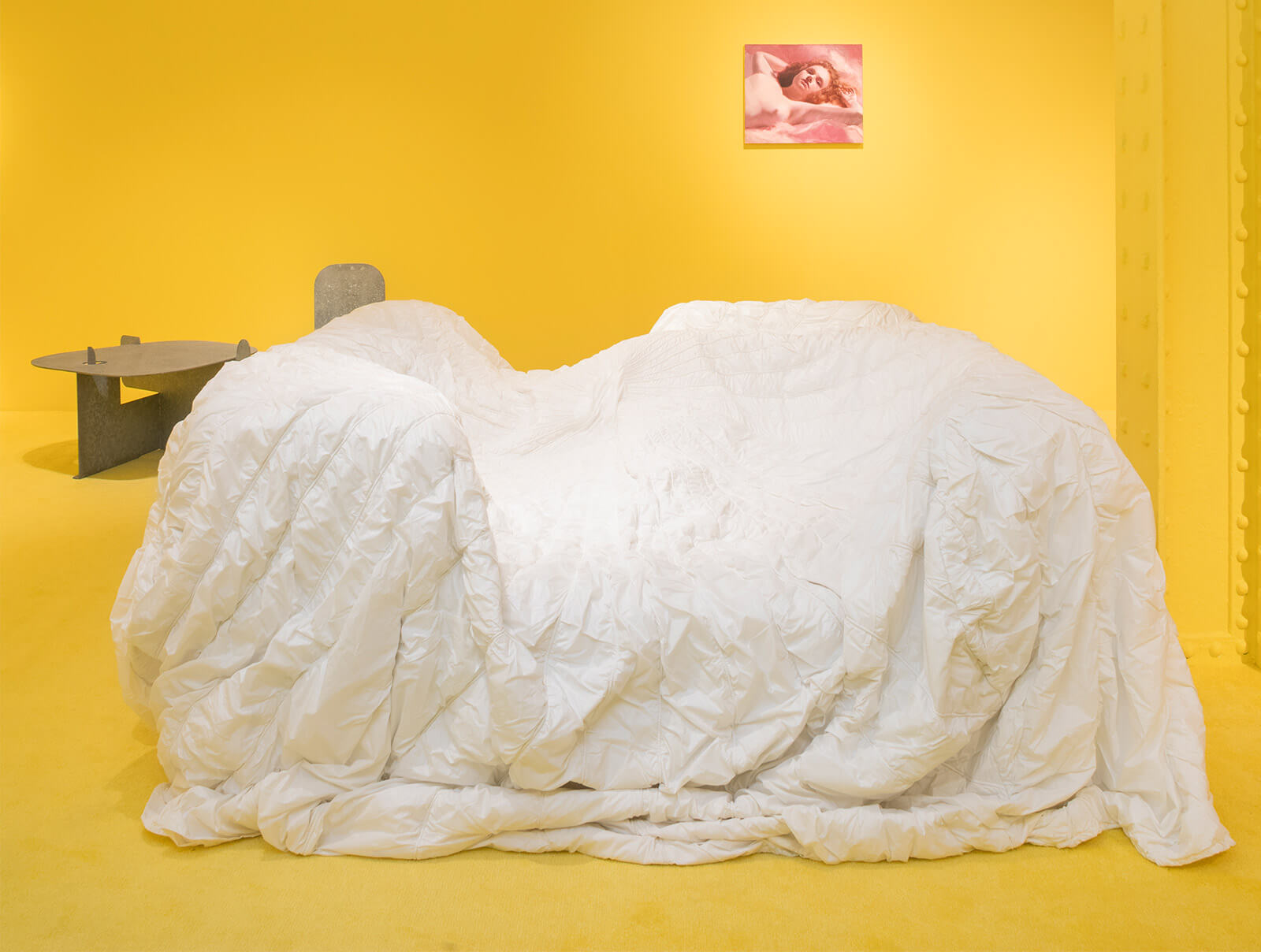

ON A CHILLY January evening, visitors to the opening of Friedman Benda’s current exhibition crowded into a gallery with sunshine-yellow walls and carpet, evoking warmth befitting the exhibition theme: Comfort. But this well-conceived show, curated by Omar Sosa, offers more than meets the eye, and considerably more substance than its title suggests. Anyone who expects a gallery filled with designs for sitting or reclining will encounter something entirely different.

Installation view

COURTESY: Friedman Benda / PHOTOGRAPH: Daniel Kukla

There are 32 objects on display from a diverse assemblage of artists and designers, living and deceased, including Ettore Sottsass, Isamu Noguchi, John Chamberlain, Franz West, Andrea Zittel, Michael Anastassiades and Richard Artschwager. Seating pieces are interspersed with paintings, ceramics, and such surprises as a slanted bookcase (perhaps uncomfortable for the books), and a sculpted plaster toilet-and-sink combination, playing with conceptions of comfort, a word that itself has nuanced meaning. Not only does every individual’s idea of comfort differ, but the same object can be both pleasant to view or comfortable to experience, and uncomfortable to think about.

Bless, ‘Climate confusion assistance, Pillow hammock’, 2005 (foreground); Guillermo Santomà, ‘Toilet, sink’, 2019 (background)

COURTESY: Friedman Benda / PHOTOGRAPH: Daniel Kukla

A scholarly essay, Comfort Dissidence, by architect and teacher Pol Esteve Castelló accompanies the exhibition. Castelló notes that the absence of comfort can be liberating. He criticises the evolution of the Western house into a comfortable, regular environment as regression to a state of prescribed behaviour, more formal and ultimately lacking in feeling. The incursion of comfort in the industrialised society is, too, a “gendered history and a matter of class,” ultimately offering more comfort for men and more work for women. Calling the convenience of techno-comfort “an addictive sedative”, he agrees with philosopher Herbert Marcuse and author Aldous Huxley that suffering and danger can liberate us from the constraints of comfort. As comfort becomes a weapon, an uncomfortable space, which enables free expression, is pleasurable. The interesting but somewhat abstruse essay offers food for thought about the idea of comfort, but doesn’t do much to explain the exhibition itself.

John Chamberlain, ‘Couch’, circa 1970

COURTESY: Friedman Benda / PHOTOGRAPH: Daniel Kukla

Exhibition curator Sosa, a creative director and co-founder of the avant-garde magazine Apartamento, puts it more simply. “I’ve never curated an exhibition before. Doing the project put me outside my comfort zone, so I thought it would be interesting to explore the concept.” Walking through the show, he pointed out objects where the reference to comfort was oblique or even arguable. John Chamberlain’s ‘Couch’, an inviting slab of carved foam wrapped in gathers of parachute cloth, needs no explanation, but the soft vinyl ‘Canapé Homme Géant’ by Nicola L, is a backless sofa in the form of a truncated male figure whose dissected extremities reference the oppression of women.

From left to right: Nicola L, ‘Canapé Homme Géant’, 1970-79; Simone Fattal, ‘Standing Man’, 2009 and ‘Woman Poet Sitting by the Sea’, 2004; George Condo, ‘Smiling Young Woman’, 2008; Nancy Grossman, ‘Snarl’, 1988

COURTESY: Friedman Benda / PHOTOGRAPH: Daniel Kukla

Objects like an aggressive George Condo portrait and a zipper-covered black vinyl head by Nancy Grossman both simultaneously attract and antagonise, evoking a craving for gentler stimuli.

From left to right: Nancy Grossman, ‘Snarl’, 1988; Gaetano Pesce, ‘Golgotha Chair’, 1972; Isamu Noguchi, ‘Pierced Seat’, 1982-83

COURTESY: Friedman Benda / PHOTOGRAPH: Daniel Kukla

Sosa sees the undulating surfaces of Gaetano Pesce’s ‘Golgotha’ chair as counterpoints to the rough-and-polished contrasts in Max Lamb’s ‘Tonalite Boulder Chair #8’ chair, speculating on artists’ decisions in forming a chair, an object traditionally associated with comfort. “I was thinking about how designers choose how to shape a chair, deciding on the angle of the back, or forming the seat.”

Each object was chosen independently, though several are arranged to suggest similarities or contrasts of texture, tone and material. Andrea Zittel’s ‘Linear Sequence #2’ incorporates floor-level seating with a conventional-height banquette, contrasting Western and Eastern standards of comfort, though the invitingly-soft ‘Blanket for Two’ by Nathalie du Pasquier, tossed over the rigid banquette, questions the assumption of Western-style seat as necessarily comfortable.

Andrea Zittel, ‘Linear Sequence #2’, 2016 (foreground); Nathalie du Pasquier, ‘A Blanket for Two’, 2019 (midground); Peter Halley, ‘Another Time’, 2001 (wall); Franz West, ‘Divan’, 2003

COURTESY: Friedman Benda / PHOTOGRAPH: Daniel Kukla

Since the catalogue checklist identifies each object without citing it as an example of, or antithesis to, the curatorial theme, visitors may find it difficult to understand the reasons for their inclusion. Sosa doesn’t expect them to agree with his reasoning, but his objective in choosing design and artworks for the show was to challenge viewers: “Not to give them the expected, but make them think about what each piece means, and whether it belongs … maybe their conclusions will be better than mine!”

Ceramic works by Takuro Kuwata and Simone Fattal, the former suggesting figural images and the latter simply amorphous forms with intriguingly irregular surfaces, are easy on the eyes but encourage closer examination. “I like to be challenged,” Sosa says, “to live with things that annoy you, and make you question your taste. They signal your willingness to be alive.”

Sam Stewart and Laila Gohar, ‘Loaf’, 2020

COURTESY: Friedman Benda / PHOTOGRAPH: Daniel Kukla

Aesthetics aside, not everything at Friedman Benda is difficult to understand: hung between two columns in the centre of the gallery is one object that might be expected in a show about comfort … a hammock by Bless, its surface a collage of fat pillows. But the final fillip is certainly ‘Loaf’, by Sam Stewart and Laila Gohar – a limited-edition club chair composed of loaves of bread mounted on a fibreboard frame and fresh-baked by Millers and Makers, an actual bakery. Displayed in a room of its own, it emits an irresistible aroma that evokes the oft-heralded “comforts of home”.

Friedman Benda – presents an international, multi-generational roster of established and emerging designers who create historically significant work.