Detroit Month of Design

Playing a part in rejuvenating the Motor City through design and innovation.

September 2021

Noguchi’s Hart Plaza and Detroit skyline

COURTESY: Discard Detroit

DETROIT’S STATUS AS the only UNESCO City of Design in the US is a testimony to the city’s multidisciplinary talent pool – according to Kiana Wenzell, Design Core Detroit’s Director of Culture and Community. “Due to Detroit’s manufacturing history, we have the highest concentration of industrial designers in America,” she tells The Design Edit. In addition to the many influential design schools in the city – such as the Cranbrook Academy of Art and College for Creative Studies – Wenzell adds: “We have the highest number of black architects, and the National Organization of Minority Architects was established here in 1971.”

Wenzell was a participant in the first Detroit Month of Design (DMD) in 2015, with tours of the Lafayette Park complex designed by Mies van der Rohe. “I was living in one of the pavilion units after college but I wasn’t aware that this was a van der Rohe building!” she remembers. The realisation prompted her to introduce the park and the surrounding buildings to the general public through guided tours. This firsthand communication with the community through design is now central to Wenzell’s role, as well as this year’s exhibitions such as ‘Discard Detroit’ or ‘Illuminate’.

A re-release of MCM classics including Bertoia, Wassily, Noguchi, Mies van der Rohe with graphics by Mike Han

COURTESY: Discard Detroit

Detroit’s diverse creative energy is evident across the Motor City throughout September as DMD looks at the city’s future and feeds into Detroit’s recently blossoming urban development, which has sustainability and access in mind.

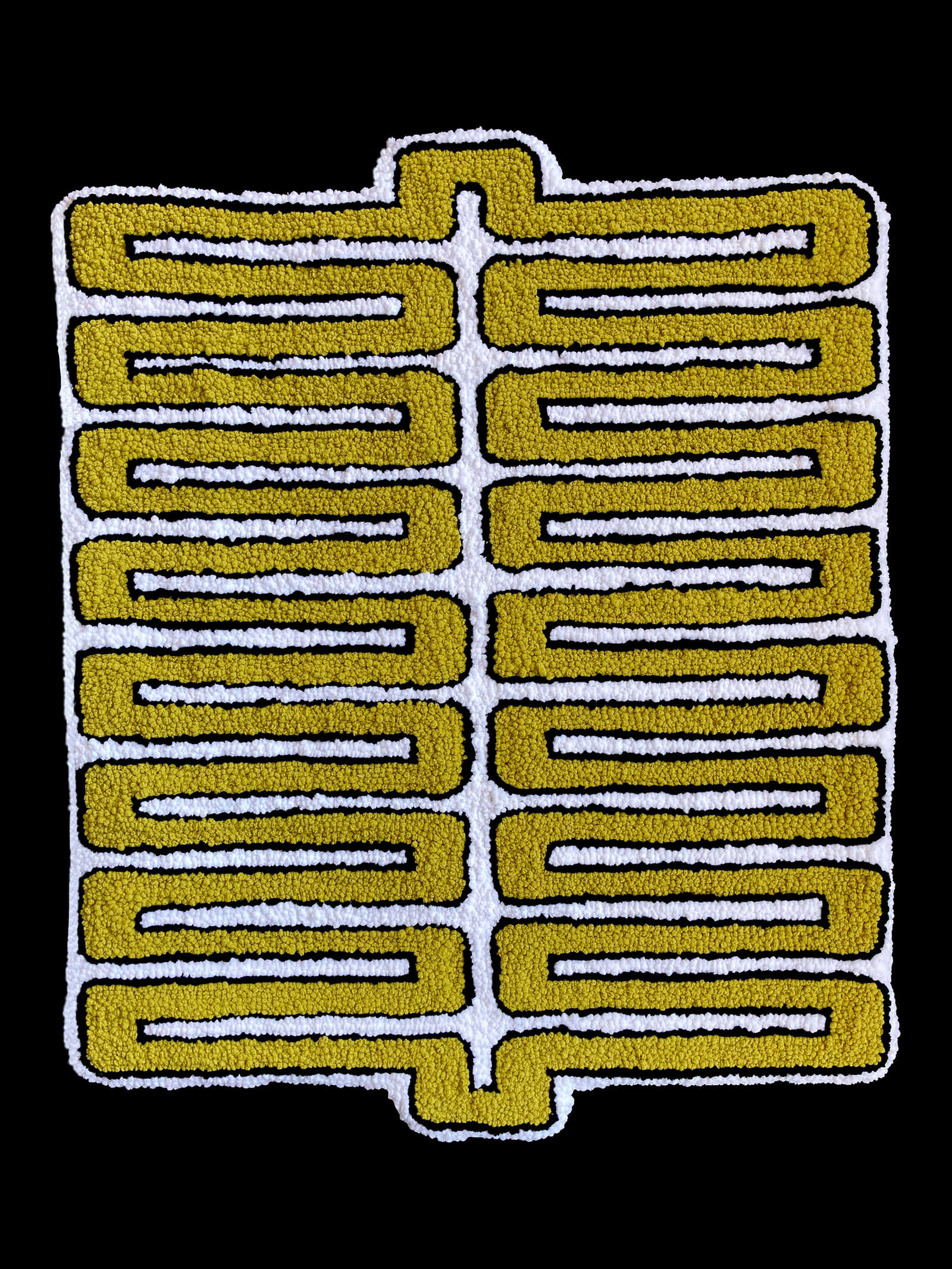

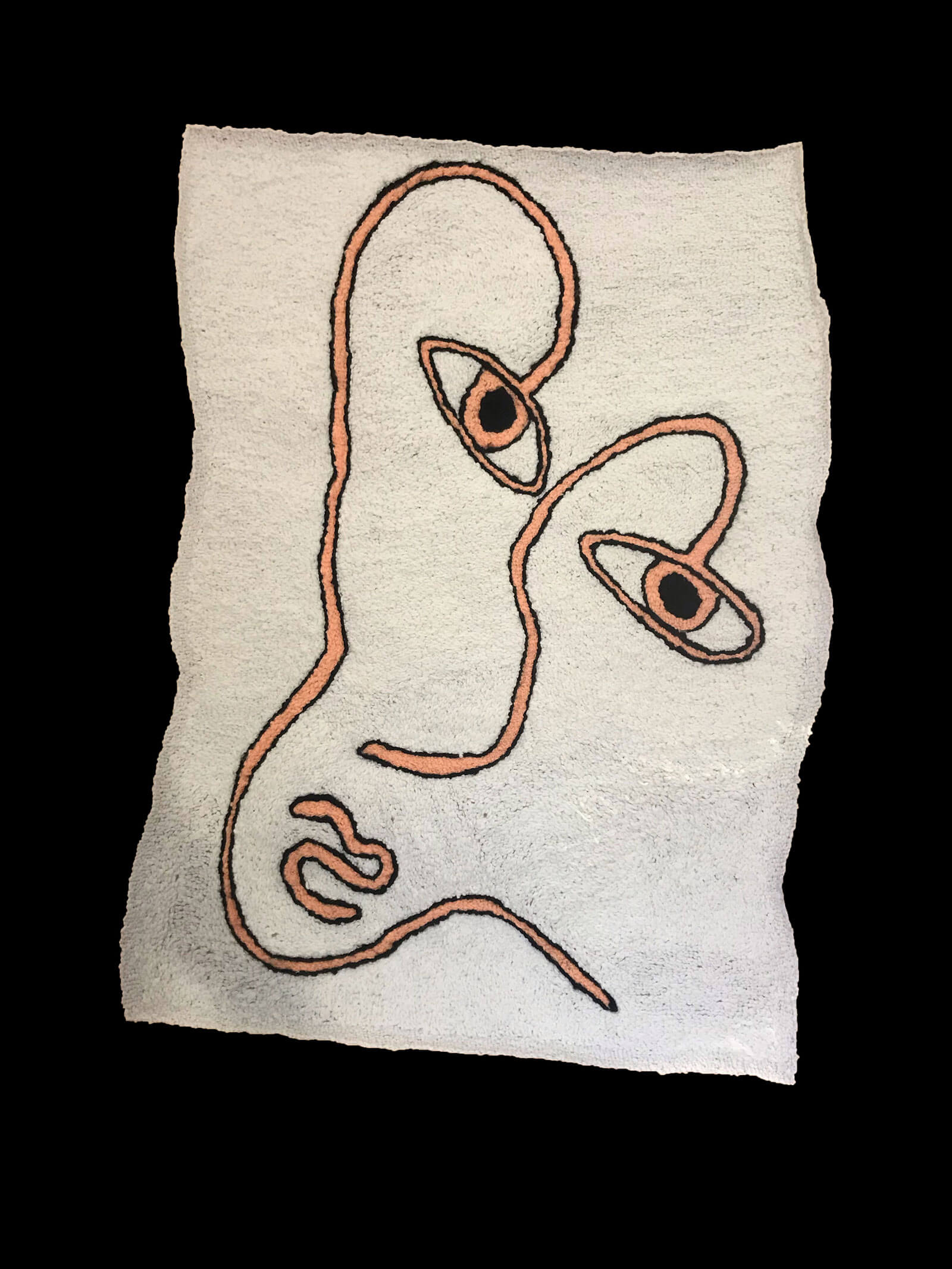

Joseph Rosales textile

COURTESY: Detroit Month of Design

Organised by Design Core, a women-led initiative that fosters community-conscious local design, DMD’s aim is to offer a marketplace for local makers and thinkers, as well building global connections with other UNESCO cities. The programme underlines, “our future through innovative design,” says Wenzell. “Besides how we design, we ask who gets to design,” she adds.

Cody Norman at work

COURTESY: Next:Space

What started in 2011 as a five-day festival to connect micro-businesses with manufacturing giants such as Ford or General Motors, has evolved into a multi-faceted event with diverse disciplines – such as landscape design and VR animation. Over eighty events – including exhibitions, talks, installations and workshops – are peppered across fifty locations throughout different neighbourhoods. “Wherever you’re located, there are three or four events within your radius,” Wenzell promises.

Joseph Rosales textile

COURTESY: Detroit Month of Design

A collaboration between artist Mike Han, design studio Synecdoche Design and photographer Ryan Southen, ‘Discard Detroit’ is a love song to Midcentury Modern which arguably owes its foundations to Cranbrook Academy of Art alumni – such as Charles and Ray Eames or Florence Knoll. The project started with Han asking Lisa Suave from Synecdoche Design if he could paint over a Isamu Noguchi table. “She agreed, which shook me, and one table evolved into a collection and a concept,” says Han. He painted the furniture with his street art-inspired forms in Hart Plaza, where there is a memorial fountain designed by none other than Noguchi himself.

They later found a Harry Bertoia side chair and Arne Jacobsen’s ‘Series 7’ chair at the basement of Suave’s late mentor. Han, whose father worked at Knoll and Herman Miller, agrees that the graffiti’s relationship with Midcentury Modern may be at odds, “but my hope is to leverage graffiti by being mindful of how to interact and add value to design and architecture,” he says about his practice, which he calls ‘Modern Vandalism’ and defines as: “The mindful practice of destroying materials and defacing objects in an effort to create value.”

Noguchi Table with graphics by Mike Han

COURTESY: Discard Detroit

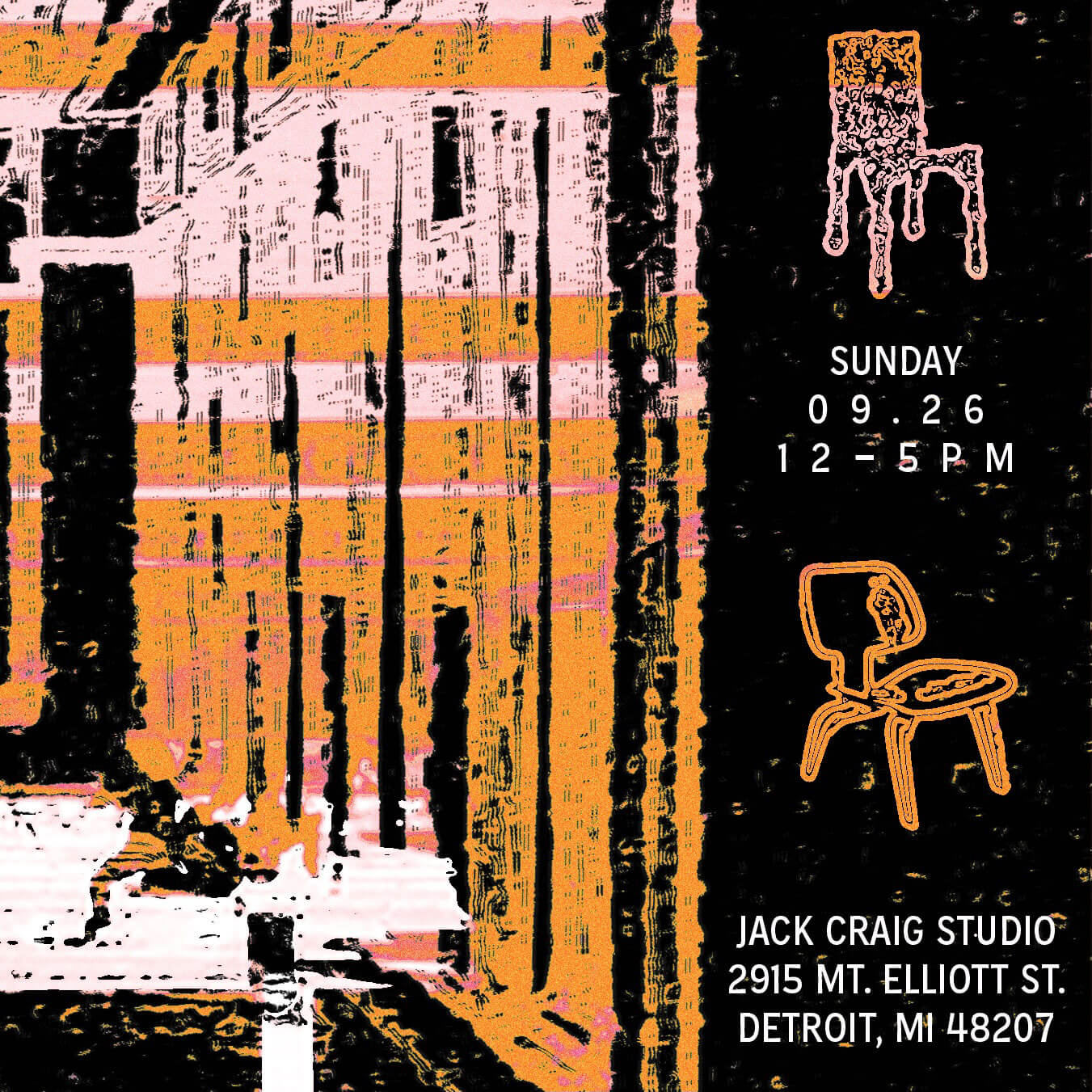

Cranbrook’s legacy in chair design, which is currently celebrated with the museum’s survey exhibition ‘With Eyes Opened’, extends to a group show of contemporary chairs by the alumni and current 3D department students at designer Jack Craig’s studio. “The strength and spirit of the school are in its ‘Where do we go from here?’ attitude, and designers are in a unique position to be agents of change through ideas and physical objects they put out into the world,” says Craig about 3D design’s role today. “More than ever, there is an awareness of the gravity that comes with that, an ethical and social responsibility to reexamine our choices, roles and attitudes by offering new ones.” Craig’s own design in the show, which is a chair he made out of melted carpet, reflects this experimentation in raising questions of sustainability. Using an ubiquitous domestic object was a challenge, but the designer, who comes from an engineering background, gave a new biology to what he calls the carpet’s “spongy fleshy tissue whose synthetic faux-ness was once designed to attract.”

Cranbrook Chair Show

COURTESY: Cranbrook Chair Show

‘Illuminate’, by contrast, features designs by students and recent graduates from Lawrence Technological University – another of Michigan’s influential design institutions. The show at the Detroit Center for Design Technology includes textile, furniture and graphic design “created with a caring, human touch,” says Kara Dawkins, the organiser. She is particularly interested in manifesting the creativity “in a city that is often underestimated by those who see it as nothing more than dilapidated and stuck in the past,” she adds. Alessandro Pagura’s CNC-cut plywood series, ‘Neomadic Furniture’, caters for constant travellers with pieces each made with three sheets of plywood, a single sheet of upholstery foam and a blanket. The convertible and screw-free design responds to a nomadic lifestyle, while not compromising a colourful neotenic aesthetic.

Alessandro Pagura, ‘Neomadic Furnishings’, 2021

COURTESY: Alessandro Pagura

In a similar spirit of ingenious but frugal recycling, designer Cody Norman’s ‘Morphogenesis’ show at Next:Space showcases bulbous vessels he created out of recycled HDPE and PP plastics using robotic 3D printing and a hand-held extrusion gun. “I collect plastic everywhere I go, but primarily from my own waste stream during the pandemic,” explains Norman. His search for “moments of reflection and intrigue” has guided him to transform the everyday material into objects that at once seem ancient and futuristic.

Cody Norman, ‘Morphogenesis’ vessels, 2021

COURTESY: Next:Space

The vessels’ mysterious silhouettes and organic surfaces invite closer inspections to discover “the unfamiliar and slightly uncomfortable,” says Norman. “This aesthetic connects to important conversations about plastics in the environment.” While the forms are inspired by natural phenomena – such as tree branches, corals and fruits – the creative process is particularly technical. The different speeds at which the 3D printing extruder and Kuka robot operate yield moments Norman describes as “over or under extrusion,” poetic flaws which the designer embraces for reflecting a discorded harmony between the natural and artificial. At every level it seems that Detroit’s history, far from a dead weight, is a source of energy – that the city’s future will be created from what has been lost and wasted but also from what, over decades, has been explored, refined, invented.